The Meaning of Invention

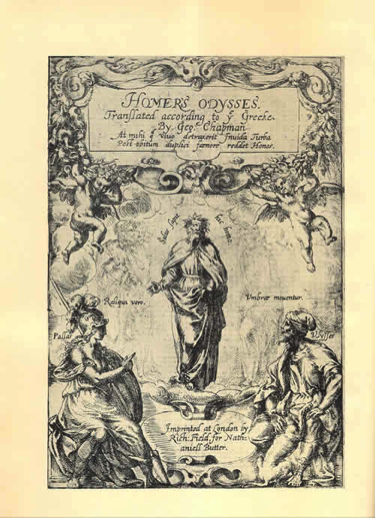

For Pope, who was endeavoring with his translation to prove that Homer was not merely the rival of Virgil but in fact his superior, the genius of the poet Homer lies in the notion of invention, which he calls “the very Foundation of Poetry.” According to the poetics of the day, Virgil was the greater artist, but Pope’s asssertion that invention “furnishes Art with all her Materials” points ahead to Romantic notions of genius and the eventual supremacy of Homer in conventional assessments of the two poets.

Here we see that fire too is linked to genius. It represents a force that is both innate in the poet as well as one that can be transferred from the poet to the audience. Pope’s assessment of the relative amounts of fire found in other poets implies that Homer is the supreme genius, because in Homeric poetry fire is found everywhere, undampened by technique or art.

The “daring fiery Spirit” that suffuses Chapman’s translation is indicative of Chapman’s own genius as a poet and his connection on that level with Homer. Pope hoped to infuse his own translation with that same fire and invention.

Inventing Ossian

Humes’s letter cuts to the heart of the questions that even today to some extent haunt Macpherson’s poetry. [16] What is the nature of the material Macpherson was claiming to translate, and what is the relationship between the poems he produced and the traditional material on which it was based? Did Macpherson “invent” Ossian and Ossianic poetry any more than Chapman or Pope invented the Iliad and Odyssey?

It was here in the final sentences Blair’s preface that the theory of a lost Highland epic was first articulated. He speaks of an oral tradition and a “race” of Bards, who transmitted the poetry from the remote past to the current day. He suggests that this epic, “which deserves to be styled an heroic poem,” could be recovered, an undertaking to which he would not only give encouragement, but which he would finance as well. Blair does not discuss in detail the presumed author of this epic, Ossian, who is the speaker of several of the fragments; he refers only to “the Bards” as authors. But Ossian was a traditional figure in Celtic myth, the son of the hero Fingal, and many Gaelic ballads are put in the mouth of Ossian, who is imagined, as Blair points out, as “the last of the heroes.” It would be the publication of Fingal, An Epic Poem (which was explicitly attributed to Ossian) in 1761 that would establish for non-Gaelic speakers the primacy of Ossian as author and primitive bard par excellence.

Ossian takes his inspiration from nature: he hears the “voice of the North” through the trees, which activates his sorrow, and the river activates his memory. The heroes of the past, including his father, Fingal, and even the next generation, his own son Oscur, have fallen like oak trees. Ossian is the last of these heroes, and all he can do is lament past glory.

This conception of the nature of epic, established well before Macpherson began his series of translations, was so powerful that, as Margaret Rubel has noted, the composition of epic poetry had virtually ceased in Britain by the 1760s. Epic was understood to be the natural and spontaneous expression of the culture that produced it, in either the so-called “Savage” or “Barbarian” phase. [39] In fact, as Rubel’s study documents, the works of Homer and Ossian came to be regarded as the quintessential examples of the Barbarian and Savage periods respectively in the history of societies. This tendency to interpret poetry as a witness to and product of the time period in which it was composed gained momentum after the publication of the Works of Ossian, but had its roots already firmly established in the work of Blackwell on Homer, and is most evident in Blair’s Dissertation, which was first published in 1763 and accompanied Macpherson’s translations in editions published from 1765 onward. [40]

This passage, which appears near the beginning of the essay, sets up an important premise that operates throughout Blair’s Dissertation: the authentic language of a primitive bard is naturally simple, that is, without artifice and ornament, but also “poetical” and “metaphorical,” because language has not yet advanced far enough to describe things in direct terms. Primitive poetry is likewise by definition full of undisguised emotion and unrestrained passion (in other parts of the Dissertation this is called “fire”) because primitive peoples have not learned to restrain their emotions. The “uncovered simplicity of nature” was, as we have seen, something often admired in Homer’s language and a point on which Pope was criticized. Blair, too, faults Pope for his overly ornate and metered translations, arguing that through prose is the only way to capture Homer’s simplicity: “Mr. Pope’s translation of Homer can be of no use to us here. The parallel is altogether unfair between prose, and the imposing harmony of flowing numbers. It is only by viewing Homer in the simplicity of a prose translation, that we can form any comparison between the two bards.” [42]

This passage illustrates well the approach that Blair takes throughout. Homeric poetry is more sophisticated than Ossianic poetry because Homer’s society is more advanced than Ossian’s. But Ossian’s ideas are better suited to poetry, and, as a poet in a more primitive society, Ossian has more “fire” and is closer to “genius” than Homer. In Blair’s critical framework, the very things that make Homer and Virgil more sophisticated are their downfall:

Wherever Ossian and Homer are compared, it is found that Homer is technically superior, but Ossian is nevertheless the better poet. Ossian is better because he is rougher, cruder, simpler, less refined and ornate, and above all, because he is more impassioned and unrestrained in his emotions. A similar comparison can be made between Homer and Virgil. Whereas Homer is merely “affected,” Virgil is downright lifeless. There is an inverse relationship between artistry and emotion, with the result that Virgil’s poetry, composed in a far more advanced stated of society than Homer’s or Ossian’s, cannot possibly inspire emotion in the reader: “His perfect hero, Aeneas, is an unanimated, insipid personage, whom we may pretend to admire, but whom no one can heartily love.” [45]

For Macpherson and Blair, echoes of Homer in his Ossianic poetry are not evidence of poetic artistry, designed allusions, or, as Macpherson’s critics would attempt to show, plagiarism and forgery. They were instead proof of Ossian’s—and Homer’s—primitive genius and connection to nature. It is presumably for this very reason that Macpherson does not hesitate to point out what are for us revealing similarities between passages in his Ossianic translations and the poetry of Homer and Virgil.

Aristotle’s ideas about good poetry are derived from Homer, because Homeric poetry is by definition good poetry. And Homer is guided by nature alone, as is Ossian. Therefore Ossianic poetry, is not surprisingly, good poetry according to the rules of Aristotle. Blair’s Dissertation therefore is not a rejection of Homer and the Classical standards that still very much governed criticism in the 1760s. Who Homer was and how he operated had changed since the early days of the Renaissance, but he was nevertheless the poeta sovrano (as Dante had called him), the man to beat.

If Blair’s Dissertation is any indication of current thinking about the nature of epic and its composition, we can see that for Macpherson, who studied Greek and read Homeric poetry at the University in Aberdeen and Marischal College in the 1750s (around the same time that Blair was beginning to deliver his lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres), Homer served as the blueprint for the primitive bard of “original genius.” Nowhere in Blair’s Dissertation is the existence of such a figure at the origin of the Greek epic tradition (or the presumed Scottish one) questioned or defended. When Macpherson was asked to translate Highland poetry for the Scottish literatti, Ossian did not need to be invented out of thin air, he only needed to be conjured in Homer’s image. The idea of Homer as primitive bard in the earliest phases of Greek civilization had been universalized for all civilizations to such an extent that it is even possible that Macpherson himself did not consciously choose to model his Ossian on Homer. He may simply have interpreted the song and story-telling traditions familiar from childhood within the framework of contemporary theory, and, when faced with the task of translating those traditions for a British audience, he, consciously or unconsciously, exaggerated those aspects of the traditions that would have the greatest impact. [49]

Macpherson goes on to compare the oral transmission of Ossianic poetry to the oral traditions of other cultures. Interestingly enough, he cites the transmission of Greek law as an example of a body of material that was preserved orally for many centuries, but not the Homeric epics. Is this omission an indication that Macpherson did not think of the Homeric poems as having been handed down in the same way? Certainly Blackwell, whose published writings on Homer seem to have played an important formative role in Macpherson’s education, had no knowledge whatsoever of an orally composing, illiterate Homer. His account of Homer’s life takes pains to demonstrate the means by which Homer’s impoverished mother secured him an education, so that he could ultimately write the Iliad and Odyssey—for how could they have come into existence otherwise? [51]

Wolf, writing seven years later, argues likewise: “the ancients themselves ascribed the origin of variant readings to the rhapsodes, and located in their frequent performances the principal source of Homeric corruption and interpolation.” Wolf postulated, based on comments made by Pausanias, Josephus, and Cicero, that Peisistratus “was the first to set down the poems in writing and to have put them in the order in which they are now read.” [55] Wolf is usually credited as the most influential modern proponent of this theory. But already in 1769, very shortly after the publication of the Works of Ossian, Robert Wood had suggested that Lycurgus, Peisistratus, or a similarly influential figure was responsible for the first written text of the poems. Wood compares that massive editorial project with the work of none other than Macpherson himself:

Wood imagines a Homer whose epics had disintegrated into scraps before they were reconstituted by an important figure like Lycurgus, Solon, or Peisistratus. Wood envisions for Homer the very process that Macpherson claimed for Ossian. It is partly on the basis of this passage that Kristine Haugen has recently argued that Wood and Wolf formed their theories about the transmission of Homer within the context of the Ossianic phenomenon and were directly influenced the arguments of Macpherson and Blair. [57]

Bentley’s Homer never was an epic poet; that genre was imposed on his work by others. We can contrast Bentley now with Villoison, writing a few decades later, who, like Wood, imagines a Homer who composed the Iliad and Odyssey, as epics, orally. These poems were memorized and orally transmitted through the generations largely intact but with the inevitable corruption, additions, and variations creeping in. In his introduction to the Venetus A manuscript of the Iliad, Villoison expresses the belief that the ancient scholia will allow scholars to recover the original text as Homer sang it. Wolf denies that such a recovery is possible, giving up any hope of determining Homer’s own text, and instead argues, like Bentley, that the transmitted Iliad and Odyssey are the product of a later age. [59]

In his own Dissertation , Blair likewise speaks of “preservation” by the “oral tradition” and emphasizes the exalted position of the Bards in Celtic society, contrasting them with the “strolling songsters” “in Homer’s time.” [61] In emphasizing the integrity of the surviving Ossianic poems Macpherson and Blair were attempting to counter a prevailing distrust in oral tradition. Macpherson writes in his Dissertation:

Macpherson’s Disseration was written in 1762 to accompany the publication of Temora in 1763. Macpherson was thus already aware of the skepticism with which his translations were being met. For many, the chief grounds for denying their authenticity centered around the problem of transmission. [63]

For Blair, just as Macpherson, the existence of an oral heroic song tradition was not enough to ensure the preservation of Ossian’s poetry. It was Ossian’s superiority as a poet, “held in singular esteem and veneration,” that caused his songs in particular to be remembered. Here Blair makes the comparison with Homer directly: Ossian’s epics were preserved because he was the “Homer of the Highlands.” His poetry spawned competitions at festivals that ensured that the texts of these poems remained fixed over the centuries. Both Blair and Macpherson seem to have felt that by articulating a theory of text fixation through memorization and performance in a regulated setting they could assure their readers of the authenticity of the material that Macpherson was claiming to translate. [64]

Macpherson’s Homer is once again a direct reflection of the contemporary conception of the primitive bard in his natural glory, unfettered by technique or art and sublime in his simplicity. But this conception, of which Homer was initially the defining example, is, amazingly, here being reapplied to Homer by Macpherson, precisely because Ossian has supplanted Homer as the primitive bard par excellence. Now that Ossian had been so successfully invented in Homer’s image, Homer could now be reinvented in Ossian’s.

Inventing Homer in the Twentieth Century

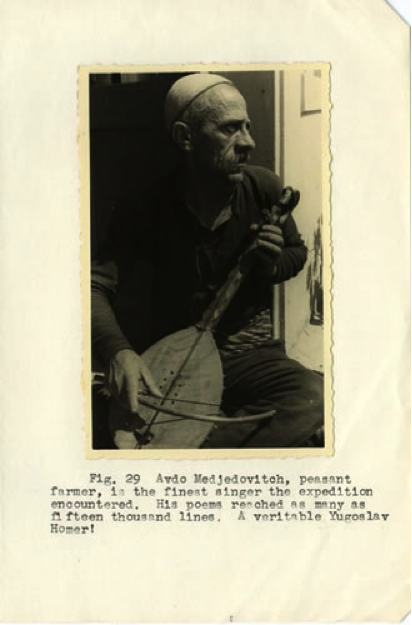

Albert Lord took photographs throughout the trip and kept a record of his experiences with a view to submitting them to a popular magazine such as National Geographic. The essay that he wrote, dated March 1937, was entitled “Across Montenegro: Searching for Gúsle Songs” and was never in fact published. [75]

Lord later wrote that for Parry Huso came to symbolize “the Yugoslav traditional singer in much the same way in which Homer was the Greek singer of tales par excellence.” He continues: “Some of the best poems collected were from singers who had heard Ćor Huso and had learned from him.” [76] Interestingly enough, Parry and Lord do not seem to have questioned the existence of Huso, though, as John Foley has demonstrated, he is clearly legendary or “at most … a historical character to whom layers of legend have accrued.” [77] So taken was Parry with the analogy between Homer and Huso that before his death he planned a series of articles entitled “Homer and Huso” which Lord completed based on Parry’s abstracts and notes. [78]

Lord himself as far as I am aware never, in print, discussed the implications of this important revision of his 1953 argument. (Lord died in the same year that Epic Singers and Oral Tradition was published.) But it is also true that Lord never speculated about the historical circumstances under which the Iliad and Odyssey might have been dictated. For Lord, the question of the text fixation of the Homeric poems was not essential; rather, he was concerned with the dynamic process, that is to say their on-going recomposition in performance.

In an exhibition catalogue entitled Troy: Dream and Reality (Troia: Traum und Wirklichkeit), West explains it for the lay person:

West’s Homer backpacks around Greece, occasionally coming up with new ideas and making corrections in the margins. Hence even the variants and apparent inconsistencies in the texts that have come down to us can be explained within a literate model of authorship.

Without addressing the question of whether or not Thomas’s argument is valid, let me just observe that, like Macpherson in the case of Ossian and West in the case of Homer, Thomas is concerned to show that it is possible that a composition by a single bard was transmitted largely intact over many centuries. Thomas’s reasoning here and in her other published work allows for the genius model of Homeric composition; the extent to which her Homer differs from other scholars is in her willingness to attribute orality, literacy, or some combination of both to the genius composer. It is my suspicion, however, that the real agenda behind the recent proliferation of studies like that of Thomas’s, studies which stress the interdependence of oral and literate forms of communication, is in fact to create a space in which the genius of Homer can continue to flourish in a way with which we (21st century Americans, Canadians, and Europeans) can feel comfortable. All in all, though we cannot deny the formative role of an oral tradition in the creation of the Homeric epics, in today’s hyperliterate and hypercivilized world we academics would prefer to have a Homer who can write.

The Dream of Ossian

Select Bibliography

Footnotes