Velimirović seems baffled that he as a musicologist was brought along rather than, say, a folklorist, philologist or anthropologist. Certainly the Academy of Sciences, which had itself collected such “songs” in the past, should have understood what was being requested. And yet somehow the uncertain valence of pesma (or pjesma) as “song” but also “poem”—and etymologically, an abstract noun, “that which is sung”—was sufficient in 1950 to lead Lord to Velimirović. [3]

But more significantly, given Parry’s fascination with bilingual singers like Salih Ugljanin and singers with knowledge of particularly long songs, one can only imagine his astonishment had he encountered the trilingual bards of Khorasan or performers of the massive Manas epic, which in its longest iterations dwarfs the Homeric epic. [5]

While Parry’s eventual choice of Yugoslavia obviously proved tremendously fruitful, it should be remembered that such choices are always brokered through relationships of politics and power, whether through formal institutions (as with Lord) or not.

On Pesma; or, The Multisensory Poetics of Poetics

Mitchell goes on to suggest that even seeing itself has a complicated relationship to the visual, with numerous ways in which the two terms are not concomitant, whether because of physiological processes or disabilities. [6]

Furthermore, he places poetry at the opposite end of the medium specific spectrum, drawing on the centuries-old practice of ekphrastic poetry, in which an object (his example is Achilles’ shield in the Iliad) is described as a palpable, visible thing—“a kind of action-at-distance between two rigorously separated sensory and semiotic tracks, one which requires completion in the mind of the reader. This is why poetry remains the most subtle, agile master-medium of the sensus communis, no matter how many spectacular multimedia inventions are devised to assault our collective sensibilities” (Mitchell 2005:263).

Media as Synaesthetic Reduction

I. Images of Sound

In photography, Barthes hears time passing—an emergent archive rooted not only in vision but also in sound, touch, and decay. Following in the footsteps of Matthias Murko, whom he met while completing his doctoral studies at the Sorbonne, Milman Parry actively photographed the singers he recorded and the cities and landscapes which surrounded them. Unlike Murko (1951), however, Parry—or perhaps in some instances Albert Lord or one of his assistants—was also able to photograph a number of performances, in addition to the portrait photographs of singers that mark both Parry’s and Murko’s collections. That collection of photographs exhibits the passage of time through sound quite literally.

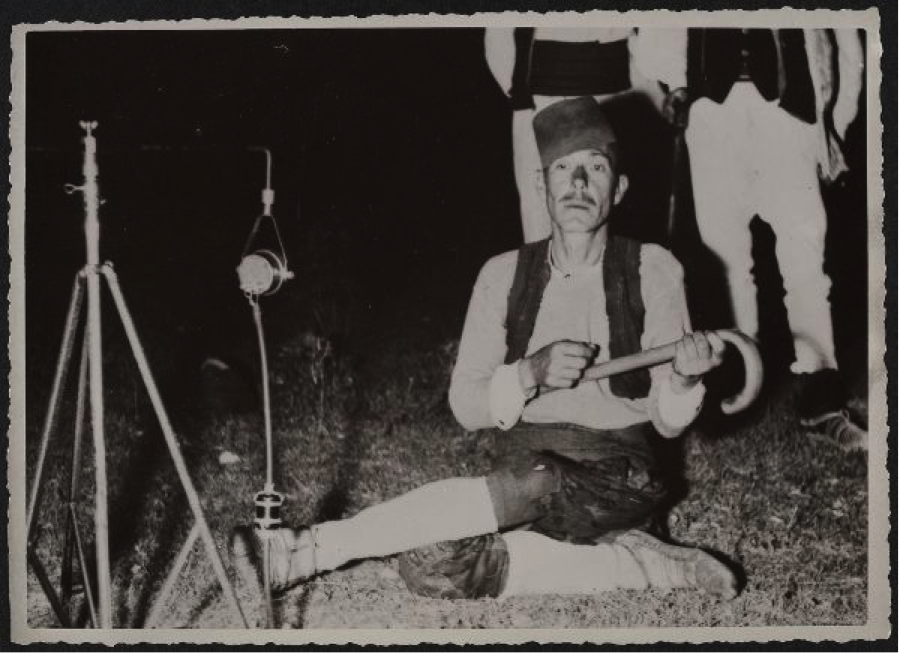

Figure 1. Jusuf Smajić recording for Milman Parry, September 1934 (MPC 0054). All photographs from the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, Harvard University.

Figure 1. Jusuf Smajić recording for Milman Parry, September 1934 (MPC 0054). All photographs from the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, Harvard University.For all the innovations of Parry’s commissioned audio apparatus, considering the audio recording being made here in isolation risks obscuring what I consider a very important, if silent, aspect of the epic being performed here: the cane as gusle. This photo in fact is part of a larger sequence, but it also serves as an iconic reminder of the many things that recordings do not capture within the context of a performance. The audio recording alone sounds like a performer sitting in front of a microphone—presumably with empty hands. The image, however, resonates with observations made by the late author and cultural critic, Ismet Rebronja (whose grandfather, incidentally, sang for and was recorded by Albert Lord in 1950). In conversations I had with him, he mentioned repeatedly what a physical process epic performance was, and that it was not uncommon for singers who did not have gusle at hand to find some other objects (rubbing sticks together, for example), to generate the kinds of kinetic rhythms that self-accompaniment provides. [9]

Figure 2. Nikola Vujnovic recording at Parry’s parlograph (MPC 0345).

Figure 2. Nikola Vujnovic recording at Parry’s parlograph (MPC 0345).

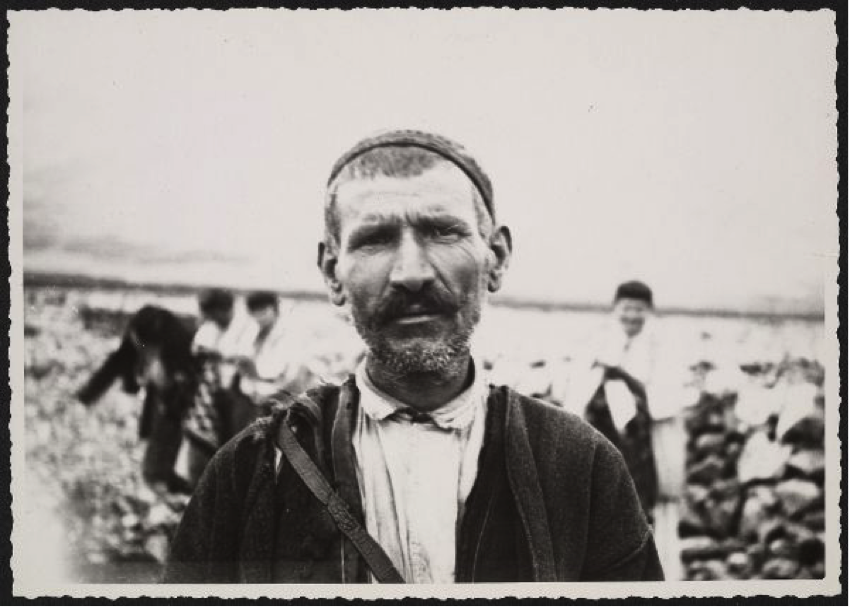

Figures 3-6. Jusuf Smajić recording in a field near Glamoč, Bosnia (MPC 0035, 0036, 0037, 0038).

Figures 3-6. Jusuf Smajić recording in a field near Glamoč, Bosnia (MPC 0035, 0036, 0037, 0038).

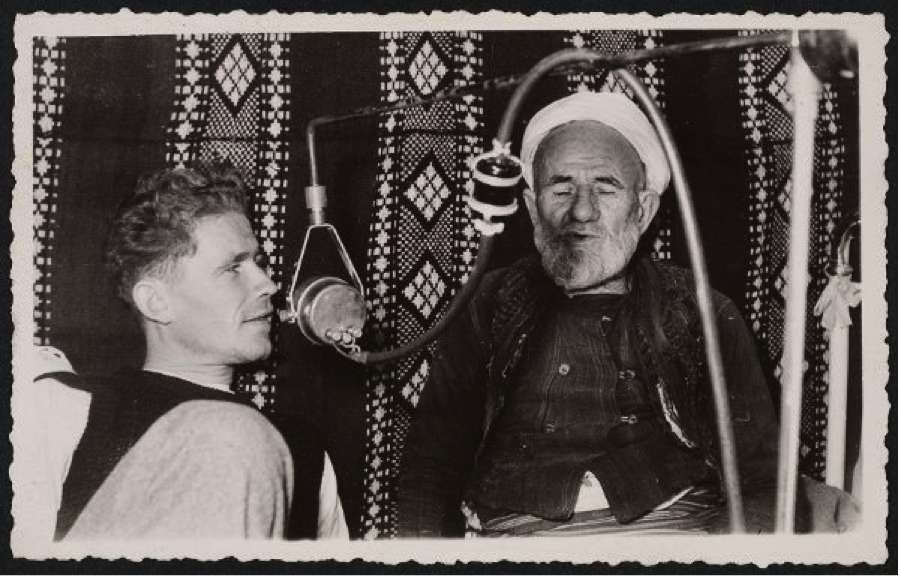

Figures 7-11. Recording at Kijevo with Ante Cicvarić (MPC 0041, 0042, 0043, 0044, 0499).

Figures 7-11. Recording at Kijevo with Ante Cicvarić (MPC 0041, 0042, 0043, 0044, 0499).II. Sounds of place

Ugljanin’s use of oral sound effects is striking, interjected spontaneously, suggesting the verbal repertoire available to a seasoned raconteur like him, despite a line of questioning from Vujnović that likely has no clear connection to poetry (and is ethically questionable, though the martial experience of singers themselves is an important theme for Parry). Vujnović presses on for several minutes in a similar manner, with prying questions about this act of violence that seem to have no connection to songs (what did the body do afterward?, did you pray to God and repent?). Ugljanin responds with further verbal sound effects, such as the body’s response (“the back springs and lurches back, ruub,” disc 1043) and the sound of blood (“like whiskey pouring out, brrrrrr,” disc 1044). [11]

The exchange shows a certain intimacy, as Vujnović (a Christian) seems to be joking with his Islamic invocation of Allah (bismillah), which elicits a brief laugh from Ugljanin (a Muslim). At the same time, the economic threats over performance suggest a power dynamic underlying the exchange. All of this is further complicated by the physicality of recording, which would necessitate that both interlocutors sit closely to the microphone—a physical intimacy demanded technologically (Fig. 12). In other words, the recording has organized the spatialization of bodies and bodily sound in this session, not unlike what we see with Smajić and Vujnović sitting in the field above or Cicvarić near the hut. The “apparatus” of these recordings thus expands beyond just the technical devices to include the space beyond them, the economic exchange involved, and the (largely unprecedented) social dynamics that inevitably would have emerged while Parry recorded in small villages around the Yugoslav countryside. Slavica Ranković has highlighted the complex, multi-party performativity that marks these interviews (2012), and while I am less inclined to characterize them as full-fledged acts of “epistemic violence” as she does, these interactions certainly warrant further study as performances in their own right with their own sensory priorities.

Figure 12. Salih Ugljanin and Nikola Vujnović share the microphone during a recording (MPC 0525)

Figure 12. Salih Ugljanin and Nikola Vujnović share the microphone during a recording (MPC 0525)III. Acoustemology and Obrov

At this point, a neighbor walked up—the current owner of the house, as I understood it—and interrupted Zaim. The two then briefly argued about what we were doing. As the years pass since I made that recording, this interruption seems increasingly central to the entire performance, though at the time I found it immensely frustrating (Fig. 13). (I distinctly remember thinking in the moment: He just ruined my video! Now I see this interaction as precisely the kinds of ethnographic reality that Parry and Lord are pushing against yet inadvertently documenting in the Smajić and Cicvarić performances.)

Figure 13. Zaim Međedović at former family home on Obrov, with (interrupting) neighbor in background (video still, June 2004)

Figure 13. Zaim Međedović at former family home on Obrov, with (interrupting) neighbor in background (video still, June 2004)I had not expected any such speech, let alone one that entangled me in the legacy of Milman Parry and Albert Lord: generations of the Međedović family, on the one hand, bound up with generations of American (and many other) scholars, on the other. The comments were gratifying but also foreshadowed a kind of mediated responsibility that I would only discover months later. For the time being, Zaim launched into the epic song, “The Wedding of Alija Bojičić”:

| Riječ prva: “Bože nam pomozi.” | Let the first word be: “O God, help us!” |

| Evo druga: “Hoće ako bogda.” | And the second: “It shall be if God wills.” |

| Samo da ga često pominjemo, | So long as we call on him often |

| da se Bogu krivo ne kunemo. | and do not swear falsely before him |

| Pa će nama Allah pomagati, | Then Allah will help us, |

| od svake muke zaklanjati, | shelter us from every torment, |

| svake muke i kaurske ruke, | from every torment and the hand of the Christian, |

| sačuvat nas hala i belaja, | preserve us from misery and misfortune |

| a i bijede gore od belaja. | and from poverty worse than misfortune. |

| … | … |

| A sad stari gosti i uvaženi, | And now old and esteemed guests, |

| da vi jednu pesmu zapevamo. | may we sing a song for you. |

| Od kako je Bosna postanula | From the time when Bosnia was formed |

| nije bolji cvijet procvateo … | no better flower bloomed. |

The song’s opening (“Let the first word be …”) is based on the opening Zaim’s father, Avdo, so often sung, a kind of expansion of the sentiments of the brief bismillah invocation made by Salih Ugljanin. Due to the physical exertion of singing, Zaim Međedović was only able to sing for about 10 minutes—a far cry from the hours-long performances his father recorded for Milman Parry. So we continued the following day at the home of a relative, as I continued to film. The video camera, able to capture sound and image (with a reasonable degree of verisimilitude), had served to catalyze a certain type of performance and a whole network of activities of memory. But even video is only able to collect an exteriority of those memories: an index through speech, as when Zaim recounts his experience; or a facade, literally and figuratively, of the house on that hillside and its rich family history; or even simply a framed viewing, whereby Zaim is visible but friends and relatives gathered (as well as myself, as camera operator) are not. Memory is sheared, even as it is preserved.

Media as Synaesthetic Catalyst

Indeed, in this case, media not only mediated, but caused our relationship to flourish, contrary to a certain notion within anthropology and ethnomusicology that imagines media as primarily disrupting otherwise “natural” interactions.

Of course, people keep all sorts of photos. But returning back to Zaim’s comments, the fact that Lord had apparently distributed photos to singers he worked with even only briefly suggests that he shared what he gathered with the singers he met. The Šijakoskis only recorded a few songs for Lord (LN 141-145b, 182-185); presumably Lord would have been even more likely to bring/send back duplicate recordings with to other singers with whom he worked more extensively, like Avdo Međedović. (Perhaps Zaim never received such media remittances because Lord’s attentions were focused on Avdo, the main singer of the family, rather than his son Zaim). In any case, I was struck to hear Zaim criticize me during a visit in May 2012 for not bringing back copies of the media I had made. I reminded him that I had already done so and offered to make another copy if needed, but he assured me it would not be necessary. The entire exchange offered a sobering reminder that the writing-down systems of media can both prompt memory and also displace it, much as Plato’s King Thamos argues in the Phaedrus (cf. also Derrida 1981). [15]

As if an emblem of the whole tradition, Zaim was fighting against (literal) oblivion, or zaborav, a longstanding component of Bosnian oral poetry (cf. Kunić 2012).

Abbreviations

Works cited

Footnotes

[ back ] 2. Miloš Velimirović, interview with author, July 16, 2007. Video of this interview segment can be seen here: https://vimeo.com/104102200.

[ back ] 3. Peter Skok writes the following in his 1971 (Croato-Serbian) etymological dictionary: “Old derivatives [izvedenice] from the base [osnova] pê- are numerous: with the suffix –sn for an abstract noun (compare basna, v.) pjêsan, genitive –sni … From there also Vuk’s pjesnarica. In this form the assimilation p – n > p – m appears … pjesma = (in ikavijan dialect) pisma (Kačić), the appearance common in written language.” (1971:672). Just as interesting as the formal linguistic trajectory here are the examples Skok gives: Vuk Karadžić and Andrija Kačić-Miošić, both of whom play important roles in the cultural space between orality and writing. Indeed, Parry’s and Lord’s efforts are often (always?) responding to Karadžić, while the writings of authors like Kačić-Miošić leave traces of a rich oral culture that hint at the fluid movements between these two (too rigid) categories.

[ back ] 4. In his own writings, Milman Parry highlights three scholars whose writings on epic he deemed reliable, while also hinting at the political pragmatics of his choice: “I found myself in the position of speaking about the nature of oral style almost purely on the basis of a logical reasoning from the characteristics of Homeric style, whereas what information I had about oral style as it could be seen in actual practice was due to what I had been able to gather here and there from the remarks of different authors who, save in a few cases—that of Murko and Gesemann for the Southslavic poetries, and of Radloff for the Kirgiz-Tartar poetry—were apt to be haphazard and fragmentary—and I could well fear, misleading. Of the various oral poetries for which I could obtain enough information the Southslavic seemed to be the most suitable for a study which I had in mind, to give that knowledge of a still living oral poetry which I saw to be needed if I were to go on with any sureness in my study of Homer” (1971:440).

[ back ] 5. On bards of (Iranian) Khorasan, cf. Youssefzadeh 2002. On Manas cf. Reichl 2000, Köçümkulkïzï 2005, van der Heide 2008.

[ back ] 6. Caroline Jones (2006) also explores Greenberg’s ideas of “opticality” and “eyesight alone,” situating the formation of these ideas in a process she terms “the bureaucratization of the senses.” Whether disciplined (Mitchell) or bureaucratized (Jones), the assumption of clear-cut distinctions between the senses that prevailed through much of 20th-century art history proves poorly suited to deal with the multisensory complexities of oral poetry. There is a certain irony in these theories that proved so adept at explaining some of the most avant-garde modern art of the century, yet failed to adequately explain genres like oral poetry that have been the subject of such discussions for millennia, dating back at least to Aristotle’s Poetics.

[ back ] 7. Arlette Farge (2013) and Carolyn Steedman (2001) address some of these sensory configurations of the archive itself, including smell and taste (Farge’s book, The Allure of the Archives, is originally titled in French, Le Goût de l’archive, the taste of the archive, 1989). I thank Wolfgang Ernst for his relentless curiosity during a recent visit to the Milman Parry Collection in which he asked repeatedly to try each of the dozen or so wire and tape recorders lying (mostly) buried in the archive. He finally found a playable piece of media on the very last—a tape recording that sounds like Bulgarian poetry, but again with no metadata to tell a more complete story. I discuss this interaction, as well as related cases, in McMurray 2015.

[ back ] 8. In addition to the archival afterlife of the Smajić images I discuss here, these photographs have also led to an important expansion of the archive through conversations and correspondence with descendants and relatives of Smajić who have been able to share more about his musical skills and verbal artistry. (He was also renowned for his Islamic recitation skills.) I discuss this further elsewhere (McMurray 2019).

[ back ] 9. Interview with author, June 7, 2004.

[ back ] 10. https://sds.lib.harvard.edu/sds/audio/462511918, disc 1043. Audio recordings are from the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, Harvard University.

[ back ] 11. In response to the question about praying, Ugljanin asserts that he was acting in self-defense.

[ back ] 12. Video of Zaim’s speech can be seen at: https://vimeo.com/104101820. His performance of an epic song can be seen at: https://vimeo.com/104101821.

[ back ] 13. This social aspect of media is increasingly obvious in the years that have passed since this essay was first written. But even well before “social media,” it has long been clear that media mediated people and their relationships (among other things). Lisa Gitelman’s pithy formulation of media as “socially realized structures of communication” (2006:7) thus seems especially useful here, not only for recordings of oral poetry but also the poetry itself.

[ back ] 14. Personal interview/visit, June 20, 2009.

[ back ] 15. Prior to my 2012 visit, Zaim had sadly suffered from a stroke and struggled to converse with the same clarity as he had eight years earlier (which I discuss briefly in McMurray 2012). I hesitate to read too much into any conversation from that visit given his health circumstances. But