It is difficult to know where to begin or end when writing the intellectual biography of a woman who has spent all but the first six years of her life as a student, a scholar, a professor and a university administrator. [1] So, taking a page from Lily Macrakis’s own award-winning biography on Eleftherios Venizelos (Macrakis 1992), we will concern ourselves here only with her “early years,” in part because fewer of her friends and colleagues in the United States will know about this period of her life, and in part because by the mid-1960s, where this short biography ends, we find Lily well equipped to do all the things she will go on to do, and which this volume so richly celebrates—teach, research and write modern Greek history, as well as act as the chair of her department at Regis College, as a facilitator of organizations and conferences, as President of the Modern Greek Studies Association and promoter of modern Greek history and culture in America, and as the Academic Dean of Hellenic College.

Beginnings

Lily’s mother came from a distinguished Patras family. Her grandmother, Aglaia (for whom she is named), was a member of the Gerokostopoulos family, which had been in Patras since the eighteenth century and had produced a number of important political figures, including Lily’s great-great-uncle, who had been the first Minister of Education after the Greek Revolution. She was an outgoing and socially-minded woman, who founded a summer school and holiday camp for poor children, which Lily remembers visiting as a five year-old child. [2] Her grandfather, Loukas, was a Karabini, a family established in Patras by the seventeenth century and one that had grown rich from the currant trade. Lily’s papou Karabini was the director of the largest currant exporting firm in Patras, the Kollas Company. Although he was formidable and slightly terrifying (Lily’s father always referred to him as “the Bavarian” because of his blond hair, blue eyes and stern ways), he used to spend long summer evenings on the veranda of his summer house with Lily, teaching her the names of the stars and the constellations. [3] The couple had three daughters, Irini—Lily’s mother—Kalliopi and Margharita (called Rita). Besides their house in Patras’s Psilalonia neighborhood, they had a summer house on the sea at Midilogli, where Lily would spend many of her childhood holidays.

In contrast, Lily’s father’s family was nowhere near so grand. Her father, Chryssanthos Chryssanthacopoulos, born in 1888, came from Gargalianoi, in the western Peloponnese, and was from a family of local landowners. In 1906, [4] his father sent him to Chicago to make his fortune, but he loathed it, and was back in Greece within the year, none the richer, but with good English and a new appreciation for American cars. After he returned to Greece, he attended a two-year business school and then moved to Athens. His career after college was frequently interrupted by military service. He was part of that unfortunate generation of Greek men who fought in three wars: the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), World War I and the Asia Minor Campaign (1919–1922). In spite of all the stops and starts, by the early 1920s he had established himself as a stockbroker in Athens.

In 1922, his older brother George, an employee of “the Bavarian,” rather boldly suggested to his boss that his clever and successful younger brother, now 34, might make an excellent husband for one of the three Karabini daughters. And, as it turned out, Chryssanthos Chryssanthacopoulos was, indeed, an excellent prospect. Although his family did not have the social standing of the Karabini, he was a very successful, self-made man, one well-established in his career, a virtue that the father of three unmarried daughters doubtless appreciated. After a first meeting between father and prospective son-in-law, a private dinner was arranged between him and the eldest daughter, Irini, a carefully and very traditionally brought up girl of seventeen. She played the piano beautifully, had impeccable manners, good French and English, but like most Greek girls of her generation and social class, she had never before been alone with a man who was not a relative. Lily’s father was impressed by what he saw, and so, at the end of their meal together he informed her that he would like to marry her. On hearing this, she began to cry. Gentleman that he was, he promised to tell her father that he had decided against the match, so that she would not have to marry him. But she told him, as she wept, that she was not crying because she objected to the match, but simply because she did not know what was going on, had never spent the evening alone with a stranger and had no idea what he was talking about. Apparently no one had told her the purpose of the dinner. And so, they married, and she went, as the seventeen-year-old bride of a husband twice her age, to Athens.

By the time she arrived in Athens her husband already had a wide circle of friends, mostly bankers and politicians, who were Dhimokratiko Komma (center-left) in their politics and their outlook. [5] The couple immediately bought a three-story neoclassical house on Thiras Street, near the Plateia Agamon (now Plateia Amerikis), which became Lily’s childhood home (see Figure 1), and lived in its elegantly decorated top-floor apartment. Along with a house, her father also acquired a convertible around this time—family legend has it that it was the first Studebaker in Greece—driven, since Lily’s father did not know how, by a chauffeur.

Within months of leaving her parents’ home in Patras, Lily’s mother turned her back on at least some of her strict upbringing (she remained extremely conventional, though, in many ways), and took full advantage of the fact that she had married a tolerant, forward-looking man and bon viveur. She bobbed her hair, threw away her corset and became a “modern girl,” favoring tight-fitting cloche hats, flat-fronted dresses, fur coats and two-toned shoes (see Figure 2). In the first year of their marriage, Lily’s parents often went dancing, and her beautiful, young mother was famous among their friends for the perfection of her Charleston. She became pregnant, however, that first year, and Eugenia, always known as Jenny, was born. Lily arrived three years later, initially much to the horror of her father. When he entered the house after her mother had given birth to her, and asked “what is it?” and was told “a girl,” he turned on his heels and left the house without seeing either mother or child. But he soon got over his disappointment and only revealed to Lily how devastating it had been not to have a son when Lily’s own first child, Stavros, was born. Throughout her pregnancy he assured her again and again that all he cared about was that she and the baby were healthy, but when he was told that he had a grandson, he was over the moon, and Lily said to him, “I thought you didn’t care if I had a boy or girl.” His surprised response was “And you believed me?” Still, throughout Jenny’s and Lily’s childhood, he was a doting father and a man, perhaps because he had no sons, who generally supported the girls’ academic ambitions.

Lily’s parents, like the parents of all her friends, hired a nurse when their children were born. Lily’s dadá, from Naxos, was an illiterate village girl with a young child of her own, a woman who not only cared for Lily as a baby and toddler, but occasionally served as her wet nurse (see Figure 3). A different kind of woman was brought into the house by the family when the sisters were a little older, this time to supervise their early education. Her parents employed a series of governesses for the girls, a new one arriving every year or two. Lily disliked the one from Paris, but she was very fond of an Italian woman from Egypt, who spent two years with the family, and who had come to Greece to fulfill a religious vow. Another, a Russian, had fled to Greece during the Russian Revolution. These women, unlike the family’s cook and maid, ate dinner every night with the girls. Their main duties were to teach Jenny and Lily how to play the piano and speak French. Lily, though, struggled as a little girl to speak at all, and was late in talking, perhaps because she was having to master two languages at once. One of her earliest memories (perhaps she was two or three at the time) is of sitting in the family dining room, trying to plan out a sentence that she wanted badly to say out loud. She was so delayed in her speech that her mother took her to a doctor. In the end, though, she spoke on her own, and once she did, she never uttered a word of baby talk, only perfectly formed sentences. Discerning and slightly ambivalent by nature, it is of little surprise that her first words were “comme ci, comme ça.” Her early difficulties with language were soon replaced by a shyness that marked the whole of her childhood, and although she was not shy with other children, until she was twenty, speaking to adults, even old family friends, was often an agony for her.

The Girl Intellectual

Lily loved school from the moment she started as a six-year-old second grader. She skipped first grade because by the time she was old enough for school, she already knew how to read and write and work an abacus. She was comfortable speaking French as well, thanks to the hard work of all of those live-in governesses, whom her parents continued to employ during her first couple of years at school.

From the start, she was motivated by her mother to work hard. In spite of her own truncated education—she had left high school to marry—her mother was very ambitious for her daughters, insisting that they continue the proud tradition of a long line of women in the family, who had always been first in their class. As proof, she even showed Lily the marked high school exams of older women in the family. Although Jenny, the family rebel, never worked hard enough to rank above second or third, Lily took her mother’s exhortations to heart, and from her very first year of elementary school to her last year in high school she always ranked first in her class. Since there were a few smart girls each year snapping at her heels, she not only worked diligently on assignments and exams, but strove to be a vocal participant in class, an act of will for a girl as shy as her. And when the school day was done, her studies were not. Although they ceased to have a governess early on (the governesses, the chauffeur and the Studebaker disappeared sometime between 1933 and 1935, as the Depression began to take hold in Greece), [6] Lily and her sister were still subjected to weekly piano, French and English lessons at home, not only during the school year, but in the summer as well. [7]

The one and only school Lily attended, Parthenagogio Marias Krikou, “Maria Krikou’s School for Young Ladies,” was the school of choice among the families of the bankers, professors, doctors and high-ranking government officials who made up the Chryssanthacopoulos’s social world. The school was housed in an old neoclassical mansion ten minutes’ walk from home. The lower floor was used for the little girls, and the top floors for the upper grades. Each classroom had a large wooden door pierced by a small glass window, through which the frightening face of Miss Krikou herself could often be seen scanning the room for signs of misbehavior.

Miss Krikou cut a terrifying figure. She was short, stout and homely; and in contrast to her pupils’ elegantly dressed mothers, she favored aggressively modest black dresses and an unconvincing steel-grey wig. The wig, so Lily wistfully recalls, lay at the center of all student plots, including ones involving the well-behaved Lily, but no one ever managed to steal it. The school day began each morning with Miss Krikou surveying the girls from the top of the stairs, pulling various of them out of line to scold them for improper deportment or infractions against the school’s draconian dress code. She was infamous not only for making the girls cry, but their mothers weep as well, and Lily’s mother was no exception. Miss Krikou’s one weakness was for pupils from the wealthiest families, girls who were brought to school each morning in grand, chauffeur-driven vehicles. At one point, Lily lost her standing as first in her class to a classmate with a powerful father, so Lily’s mother marched into the school to challenge her daughter’s unfair demotion. Although she triumphed in the end and returned Lily to her deserved spot, she was reduced to tears during her meeting with the headmistress.

Lily’s intellectual gifts were appreciated not only by her teachers at the school, but admired by her classmates as well. Cheating was widespread in Greek schools of the period, and for the whole of her years in school at exam time girls fought to sit next to her so they could copy from her paper or have whisper consultations with her during exams. And by the time she was fourteen or fifteen, she had become the official correspondent for her class, regularly commissioned to write elegant (and needless to say chaste) love letters to the boys with whom her classmates were infatuated.

The teaching at the Parthenagogio Krikou was traditional. Indeed, Lily recounts that some of the teachers in school handled their classes “as if they were teaching in the 1850s;” and certainly, some courses were holdovers from the nineteenth-century and demanded skills that Lily never mastered. [8] For each of her eleven year there, for example, she was required to take embroidery lessons. Lily would bring home her work each night, which she never managed to do to a very high standard, and her mother would unpick her slipshod stitches and redo them. The girls at school also took lessons in Greek dancing. Lily’s self-assessment: “I danced like a bear.” One of the most cherished goals of the school’s conservative curriculum was to teach its students how to be “good girls,” something at which Lily actually excelled, and in her early years at Parthenagogio Krikou, one of her life’s ambitions was to become a nun! [9]

From the fifth year at the Parthenagogio Krikou on, the elementary school subjects of arithmetic, reading, writing and conversational French gave way to a more demanding curriculum: Modern Greek and French literature, Ancient Greek, Latin, science, art history and history. As in many schools of the time, language instruction was dull, and the students spent months crawling through a few pages of Homer. But they eventually moved on to Xenophon, and by the last couple of years of high school they were working their way through texts by Plato. Art history classes stopped at the early nineteenth century, and the history taught in school was political in its focus and never went beyond the end of the nineteenth century. Indeed, Lily still shakes her head when she remembers the elderly man who taught history there and who, when beginning a class on the Italian Renaissance, announced “it is now time to talk about the wars of the Renaissance.” Lily, who never challenged teachers, screwed up her courage to ask “but what about culture and art?” to which the teacher replied, “oh, you can do that by yourself.”

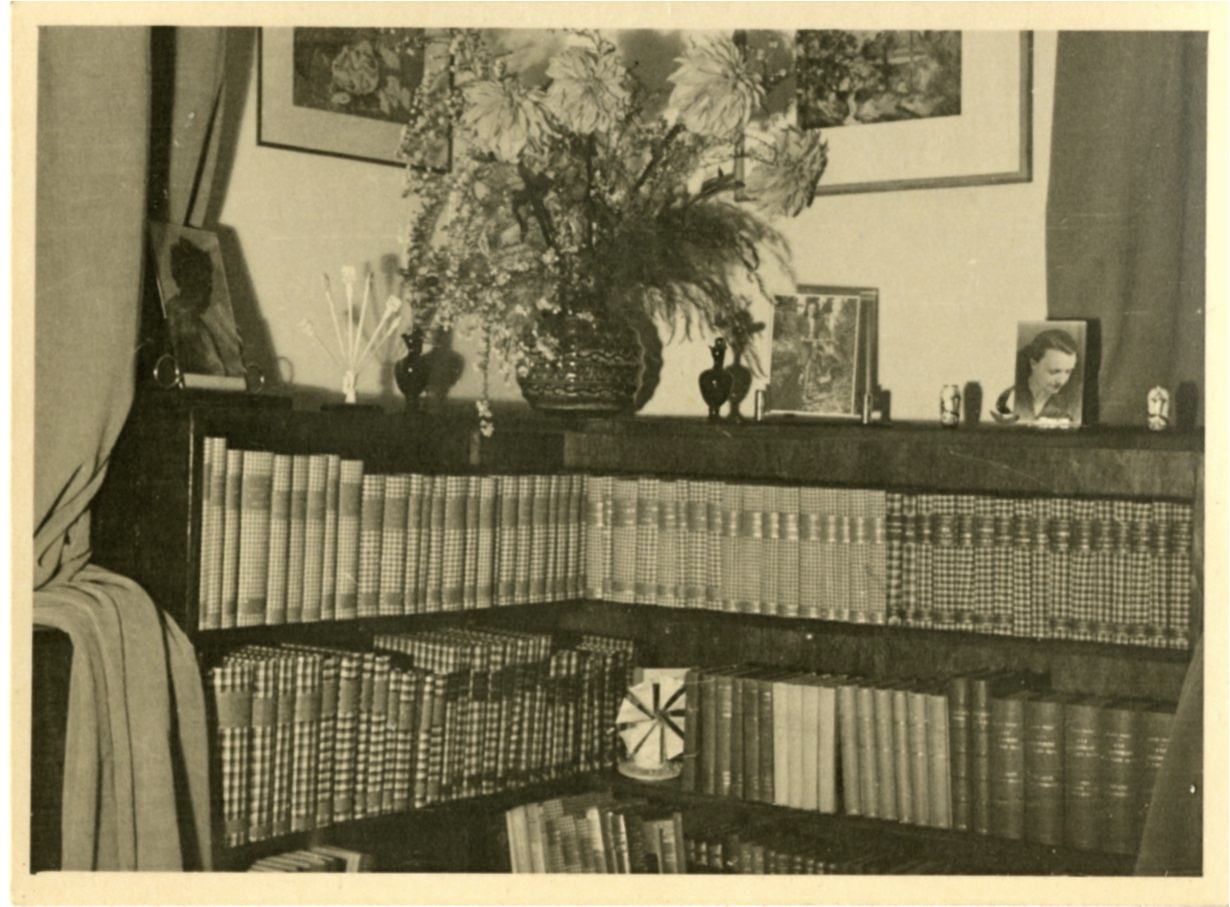

Although much of what she learned in school was not taught in an interesting way, the things she mastered there—historical chronologies, artistic styles, the intricacies of Ancient Greek and Latin grammar—lodged firmly in her head, and provided her with a solid foundation for her later studies. Perhaps as important, though, were the things she learned during these years on her own, made possible, in large part, by her early exposure to French. By the time she finished high school she had read huge amounts of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century French literature for pleasure, including the works of Racine, Voltaire and Zola, as well as some nineteenth-century English literature (although she read most of this, including the works of Dickens and Sir Walter Scott, in French translation), as well as large numbers of biographies, again, usually written in French (see Figure 4). Her godfather, George Alevizopoulos (see Figure 3), who often travelled on business to Africa and took his holidays in France, and who had an unerring eye for gifts, moved from presenting Lily with fantastic French dolls when she was very small, to books, and early on he gave her one of her most prized childhood possessions, a set of the Bibliothe`que Rose, books that began her life-long love affair with reading. An early favorite was the cloying popular children’s novel Les Petites Filles Modèles, written in the 1850s by the Comtesse de Ségur (de Ségur 1858). Whatever their shortcomings as literature, the volumes in the collection got her in the habit of reading French for pleasure, which opened up a world of European literature that otherwise would have been closed to her. Indeed, she did not read much modern Greek literature until she was an adult, introduced to much of it by her childhood friend and noted Cavafy scholar George Savidis. In any event, her own broad reading combined with the rote learning of high school prepared her well for the undergraduate courses she would eventually take in archaeology and history at the University of Athens.

A Historian in Training

Only one teacher at her school, a Miss Demopoulou, whom she encountered in her last two years there, had a real impact on Lily’s life and encouraged her to go on with her studies. Miss Demopoulou was a single woman in her thirties, part of a circle of young, university-trained, socialist historians, many of whom were teaching in private schools during the last years of the German Occupation, a group which included Nikos Svoronos and Michael Sakellariou, who would go on to have distinguished careers as academics in Greece and abroad. Besides teaching, Miss Demopoulou wrote articles about history and archaeology which were published in the newspapers. Not only was she the only real intellectual at the school, but she taught modern Greek history, an innovation in the early 1940s, since almost all history instruction at school centered on Ancient and Byzantine history, and the history of Greece under Ottoman rule. The focus of Miss Demopoulou’s class, however, was the 1821 Greek Revolution. In her course she brought all of the latest scholarship to bear, and she taught the Revolution as a series of historical controversies. This was the first time Lily was exposed to history in all its complexity and came to understand that the history of Greece could be more than patriotic hagiography. After Miss Demopoulou marked the course’s first exam, she made Lily stand in front of the class and read her essay, which the teacher praised as a minor masterpiece. That day she invited Lily to her home for tea, and spent the afternoon encouraging her to study history at university and promising to do what she could to help her secure a place there.

By this time, Lily’s sister Jenny had begun the University of Athens and was herself studying history and archaeology, and this, too, made Lily contemplate studying history at university. Knowing Lily’s growing interest in the discipline, Jenny brought her sister with her to one of her seminars, held in the basement of the Academy of Athens and taught by Michael Sakellariou, who also happened to be a friend of Miss Demopoulou. [10] In the class, he lectured about “source material” and taught his students how to read primary documents critically, something Lily had never heard about or thought about before and which she found extremely exciting. The students in the seminar, many of whom came to make up the next generation of Greek historians after the war, were completely engaged, and Lily was hooked.

While Lily was still in school and Jenny was in her first year at university, the sisters also attended classes and lectures at the French Institute. It served as an important center for intellectual life in Athens during the Occupation, and the Institute was a place where little revolutions of thought against the Germans regularly took place. The class she remembers best is the one in which attendees were asked the following question: “If Socrates came back to the Athens of today, what would he say?” Her sister took the question patriotically, and wrote an essay, read aloud in class, which held that he would climb to the top of the Acropolis and shout the question “where are all the free Greeks?” Her essay, which was a dangerous thing to have written during the Occupation, was published in France in 1946 in a collection of pieces written by Greeks at the Institute during the war (Milliex 1946:76–77). The thinly veiled discussions of contemporary history made Lily all the more interested in history as a discipline.

Her memories surrounding the French Institute are reminders of how difficult the years were in which Lily came of age. Her childhood, as idyllic as it was in so many ways, took place in dangerous times, and it is a testament to her parents that she remembers these years with such fondness, because it is clear that they did what they could to shield her from the terrors of the period. [11] For example, in March 1935, during the failed Venizelist coup, her father was arrested in a roundup of Venizelos’ followers and imprisoned for a few days. An uncle of her mother, who was the head of the high court in Greece, though, was able to secure his release. The next year, Ioannis Metaxas established his right-wing, monarchist dictatorship, something Lily’s father was very much against, and the anti-democratic police state that Metaxas imposed must have required him to tread carefully. It was during this period that Lily’s father began to be plagued by ulcers, a problem that would dog him for the rest of his life. [12] In the first year of the war, when the Greeks successfully held back the invading Italians, many of Lily’s relatives were in the army; and, of course, things got much more difficult when the Germans occupied the country. Like so many Athenians of her generation, Lily remembers sheltering with her family in the basement and listening to the not-so-distant sounds of the aerial bombardment of Piraeus; and one of her most disturbing childhood memories is of coming across the corpse of a woman in the street covered in flies: one of the hundreds of thousands of people who died of hunger during the terrible famine of 1941–1942. She hid documents in her bedroom for one of her Jewish school friends, who was eventually taken away, but fortunately survived the war, and she listened in secret each night with the rest of her family to the BBC, a capital offence. Then, in December 1944, after the Germans left the city, civil war broke out in Athens. She, her mother and her sister were forced to flee from their home in the middle of intense street fighting, with Lily literally wearing hidden gold coins sewn in a kind of corset made by her mother (!). They were detained by a group of Communist partisans, but Lily managed to talk their way free, a lucky break since the people stopped with her family but not freed, were kidnapped and taken north into the mountains. They fled to the British-controlled part of the city where her father was waiting, and the family was unable to return to their home for almost a month. [13] Still, rather than remembering her childhood as a series of hard times and unfortunate events, she is full of fond reminiscences.

At the end of school, Lily passed the national high school exam with high marks. She then sat a competitive entrance exam in history and archaeology in hopes of securing a place at the University of Athens. She received a perfect score. Her parents, particularly her mother, although single-mindedly dedicated to her doing well in school, were not enthusiastic about the girls continuing their education at the university. Her mother hoped that after the war they would go abroad, to attend finishing school. [14] But Jenny, willful and determined, had insisted on university, her dreams helped along by the fact that a number of the daughters of family friends were now pursuing degrees themselves. [15] So, by the time Lily graduated from high school, her older sister had already blazed a trail for her.

She began the University of Athens in 1944, but because of the political unrest and later civil war, it was closed for the better part of her first year. Still, students and professors continued to meet informally, and Lily and her sister read what they could on their own. Once classes resumed, she followed in her sister’s footsteps and began working towards a degree in Ancient Greek archaeology and history. This major, at the time, was very popular among women, and there was only one man in her class. She went to lectures on pre-history, Classical and Byzantine art and history. She had hoped to attend lectures on Modern Greek history as well, but found the professor very dull.

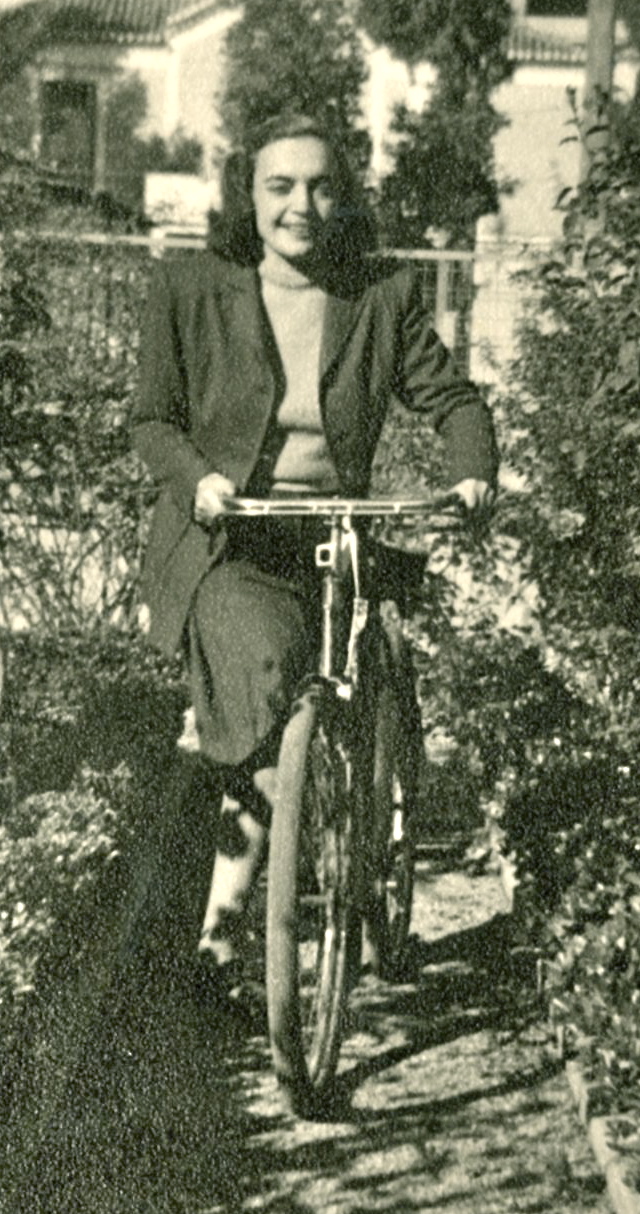

The most life-altering event that took place during her years at university had nothing, however, to do with the University, but with her sister. Jenny had always been a brilliant, outgoing golden girl and the heart and soul of a large group of friends, and Lily, even at university, continued to be her bookish, introverted shadow, and she admired her sister above all other people (see Figure 5). In December 1946, Jenny, in the throes of studying for her end of university exams, contracted measles, which by early February had developed into encephalitis. [16] Her father believed that penicillin, a drug just coming onto the market, could save her life, and he spent many desperate days trying to secure some for his daughter, but there was simply none to be found in Greece. The day the ambulance came to take her from the family apartment, as she was being carried out of the house on a stretcher, she held her little sister’s hand and repeated the words of a popular song: “Today I’m here, tomorrow I’m not.” She was dead within the week. Her parents were devastated, and Lily was consumed by survivor’s guilt and profoundly lonely for years after her death. When Jenny died, Lily resolved that the only thing she could do for her parents was to become her sister. She committed herself not only to making herself the archaeologist her sister had so wanted to be, but overnight she transformed her shy self into the outgoing, socially assured creature that her sister had been. No one who has come to know Lily after 1947 can believe that the Lily of the present, a person who has never met a stranger, is always at ease and has hundreds of friends, was not born this way. But this transformation, which she undertook as a gift to her mourning parents, also, so it turns out, was an extraordinary gift from Jenny to her young sister, because without this determined refashioning, much of Lily’s later career would have been impossible.

By the autumn of 1949, Lily had finished her course work at the University, although she had yet to take her exams, and her parents arranged for her to spend a year at Oxford in an English-language program with the daughters of one of her father’s clients. Lily jumped at the chance to spend a year in England and live, for the first time, away from home. The girls, all of whom had been brought to England at the beginning of the academic year by their over-protective Greek mamas, embraced independence as soon their mothers left. Two of Lily’s companions became dedicated smokers that year and Lily spent three glorious weeks hitchhiking around England’s West Country with an English girlfriend. [17] During her time in England, the new, outgoing Lily was the center of a large group of international students. One of the closest friends she made in Oxford was Magdi Wahba, a Copt from Cairo and the grandson of a former Egyptian prime minister, who was pursuing a degree in English literature “while he could,” because he feared that he would be spending the rest of his life running his family’s cotton business. (In actual fact he ended up as a distinguished Professor of English at Cairo University.) Two other friends she made that year were Mary Kyri, a fellow Athenian, and Mary’s future husband Edmund Keeley, an American who had spent part of his childhood in Greece, who was now in Oxford on a Rhodes scholarship. The couple are still, many decades later, good friends, and Lily and Edmund Keeley would become decades-long organizers and co-conspirators in the Modern Greek Studies Association. Also studying in Cambridge at the time was one of her childhood friends, George Savidis, who remained a close friend until his death in 1995.

At the end of her stay in England, she returned to Greece accompanied once again by her mother, and they travelled home by way of France, Switzerland and Italy, stopping for twenty days in Austria so that Lily could participate in a meeting of an international student organization. Soon after she returned to Greece, Lily travelled to Egypt to visit Magdi Wahba, taking what she still considers the most interesting trip of her life. Not only did she often visit her friend’s riverside palace, filled with impressionist and expressionist masterpieces, but she toured the country, taking in its ruins and traveling to Alexandria, which in the early 1950s was still a very Greek city.

When Lily returned from her foreign adventures, she took her end-of-university exams, and then began working in archaeology, although as a volunteer, since paid work was something her parents discouraged. Her first job, which she held for eight months, was at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens at the Agora excavations. She did not excavate, but rather worked in the back rooms, helping to identify objects as they were being unearthed. She then moved on to the Acropolis Museum, where she and three friends from university were given the opportunity to help put back together the collection of that museum, which had been secreted away in caves underneath the Acropolis during the war in order to keep it out of German hands. Many of the objects had been separated from their documentation during the war, and some of the museum files had been destroyed, so much of the collection needed to be re-identified. These women, who knew their ancient sources well and had all trained in ancient history and archaeology, spent many months working on the project.

One weekend in 1950, while she was working at the Acropolis Museum, she invited one of her friends, Liza Skouze, to come with her to a summer house rented by her family in Kifissia. Liza, in turn, invited her boyfriend, who in turn brought an old school friend of his, Michael Macrakis. The Civil War had not yet ended, and Michael was in the army, where he was finishing up four and a half very long years of military service. Both of the men had gone to Athens’ American high school, Athens College, in the suburb of Psychiko, where their families lived. Lily had spent her childhood making fun of Athens College boys, with their knickerbockers and snobby ways. But the four went to Delphi that weekend in Michael’s car, and from that moment on, Lily and Michael were inseparable (see Figure 6). They spent a year doing everything together, but in the fall of 1951, when he was finally released from the army and able to finish his exams at Athens Polytechnic, he left for the United States to pursue a Master’s degree at MIT in physics. For two long years, they wrote each other almost every day and sent one another a series of carefully posed photographs—Michael hard at work at his desk, but missing Lily; Lily in a bathing suit looking lonely, and the like. When Michael decided to pursue a Ph.D. at Harvard, he persuaded her to apply to graduate schools in the United States, and she was accepted at Radcliffe to do a master’s degree in Classical archaeology and history. And, of course, they planned to marry. Her parents, however, were dead set against these plans, and it took Lily an entire year to convince them to let her go. Initially, both her parents insisted that she stay in Greece, and they hoped that instead of studying for an advanced degree she would marry a man of their choosing. [18] Eventually, however, her father came around.

Her mother, who was Lily’s biggest support in so many things that she was to do in her life, remained implacably opposed, but her father, understanding how much she both wanted to go to graduate school and marry Michael, arranged a business trip to the U.S., so that he could accompany his daughter to Boston. As fast as Lily packed her suitcase for her trip, her mother unpacked it. But Lily was determined, and she and her father, suitcases finally packed, went first to England and then on to New York City on the Queen Mary.

Lily’s first week in America, in the fall of 1953, was the busiest week of her life. Michael met them at the docks and formally asked Lily’s father for permission to marry her. The three then travelled to Boston by train and her father helped them find and rent a small wing in a house in Belmont, where they would share the kitchen, living room and dining room with a widow and her adult daughter. Lily then went to Radcliffe to register for her courses, dressed in her elegant way (see Figure 7). On first sighting her, the Byzantine historian Speros Vryonis, then a graduate student studying under Harvard’s professor of Balkan history, turned to his boss and whispered, “Something tells me that Miss Chryssanthacopoulos is an Athenian girl.” She finished the week by getting married in Boston’s Greek Orthodox cathedral. Indeed, Lily’s week was so busy that she had to miss her first graduate seminar because it was scheduled at the same time as her wedding. With some trepidation, she sent a note of apology; but her professors were gracious about it, and the people working in the history department were enormously relieved, because Lily’s marriage meant that the department’s newest graduate student had exchanged her unwieldy nineteen-letter-long surname for the much easier and shorter “Macrakis.”

From her very first class at Harvard, she was thrilled by everything she was learning and everything she was being asked to do. She was no longer required to cram her head full of information and other people’s opinions dressed as facts, but instead was asked to develop her own considered opinions about the past. Many of the courses she took covered material that she had learned as an undergraduate, but she was being introduced to the periods she was now studying in entirely new ways. She studied mostly with Professor Sterling Dow, the noted Ancient Greek epigrapher and historian and the distinguished Byzantine and Balkans historian Robert Lee Wolff, but she also took courses in modern European history and the history of religion with William Langer and Arthur Darby Nock. For the first time in her life she was intellectually challenged and found herself studying many nights until three or four in the morning. [19]

In June 1955, pregnant with her first child, she received her A.M. in history. She did some of her course work towards her Ph.D. after her graduation and worked briefly, after her son was born, as a bibliographer at Widener, but then became pregnant with twin daughters.

Salvation

In 1960, Lily found herself at home in Belmont, Massachusetts with three young children, and she feared that she would spend the rest of her life talking to other women about babies and speaking baby-talk to her own children. As she admitted in 1961, “I was reading all this time, but it was aimless.” [20] And she probably would have ended up a Belmont matron, except for the fact that she was rescued by a remarkable experiment in social engineering, something called the Radcliffe Institute, the brainchild of Mary Bunting, president of Radcliffe College. Planning documents drawn up by Bunting make explicit the point of the new institute: to fund talented, married women with young children for “part-time study.” [21] Bunting argued that “the long-range object is to help [this kind of woman] keep pace professionally toward the day when she may elect to return to full-time participation in her chosen field.” [22]

When the new fellowship at Radcliffe was announced on 20 November 1960, the story was given page-one coverage, not only in Boston, but in newspapers across the country. [23] The New York Times’ front-page headlines read, “Radcliffe College announced yesterday a dramatic new program to harness the talents of ‘intellectually displaced women’ whose high educational attainments now remain unused.” The story reported that the planned institute for women “aims at opening new opportunities for highly educated women, especially those who have doctorates but lack a professional outlet for their talents.” [24] The Boston Globe, for its part, observed that because of the planned fellowships, “marriage need no longer be a dead end for the brainy talented college woman,” and the Christian Science Monitor commented that the program “may start a movement to save a long-neglected national resource—university educated women.” [25]

Michael saw the Times article, and immediately urged Lily to apply. She was initially reluctant, because she did not have a Ph.D. and because she worried that her children, the eldest of whom was only in kindergarten, were too young; nonetheless, her husband eventually convinced her to apply, with the promise that if she got the fellowship, they would find solutions to any problems that might arise at home. She heard nothing for weeks after she submitted her application and assumed that she had not been one of the lucky recipients. Constance Smith, the new head of the Radcliffe Institute, however, eventually called Lily, telling her that they had been swamped with over 2,400 inquiries, [26] but that Lily had made it into the final one hundred applicants, whom they were now interviewing for twenty-two fellowships. During the interview, she told Lily that she had extraordinary letters of recommendation from her old Harvard mentors Professors Wolff and Dow, and from Michael Sakellariou, whose seminar in the basement of the Academy of Athens Lily had sat in so many years before. One of the men summed her up perfectly in his letter, writing that Lily was “intelligent, ambitious [and] charming enough to lure entire species of birds off whole forests of trees.” [27]

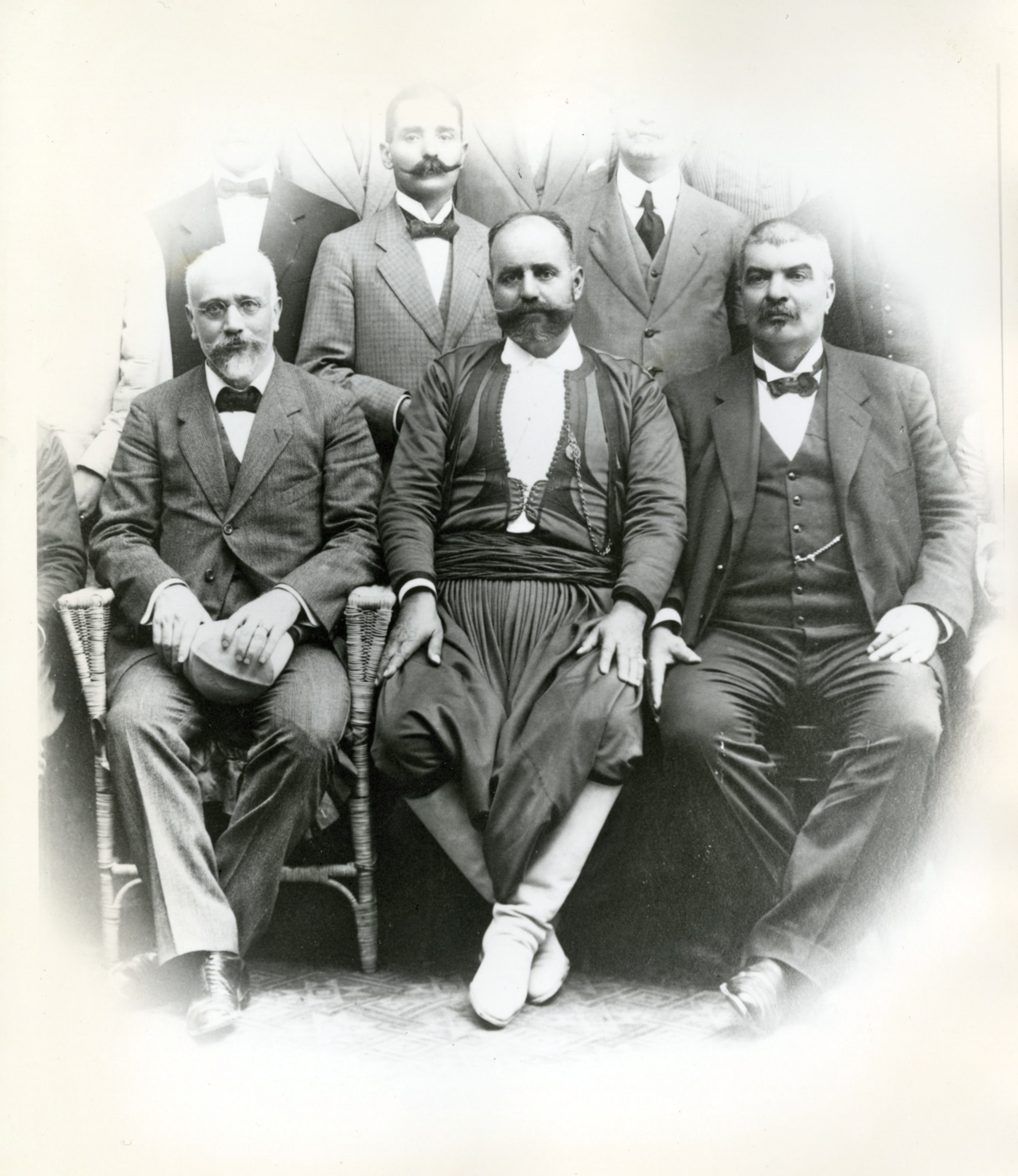

The Bunting application required a research project, and the one Lily developed was on Eleftherios Venizelos. In the years between being a full-time graduate student at Harvard and her five years in suburban exile with her babies, she had become increasingly interested in modern Greek history, and it seemed to her and her husband, who helped her think through her initial project, that his Cretan family’s connections with the Venizelists, which were close and longstanding, could lead to some very interesting work, especially since family connections would give her unprecedented access to private collections of papers still in the hands of Venizelos’s family and friends (see Figure 8). [28] Beyond this, her own father had been an active Venizelist and close friend of one of Venizelos’s sons, Sophocles. So, it seemed likely that she would be able to examine papers related to Venizelos that no historian had ever seen. She was also interested in the potential of oral history, a new idea in the early 1960s, and she hoped to interview people who had actually known Venizelos. Between her letters of recommendation and her interesting project, she had won an interview.

It is clear that people at Radcliffe were convinced both of the importance of Lily’s proposed research and her abilities as a historian, and that the main purpose of the interview was to determine whether this mother of three young children could actually commit at least part of her time to her own academic project. Constance Smith wanted her to describe, in detail, her arrangements at home, and was very happy to hear that not only did Lily have domestic help, but that her mother, who now lived with the family in Belmont part of each year, had agreed to take over more of the responsibilities of managing the house and the children. Lily also assured Smith that her son Stavros would be in school and that her twin daughters, Kristie and Michèle, would be starting nursery school that fall.

On June 2, 1961, the decision was made, and Lily, along with twenty-one other women, was awarded a fellowship and given a $3,000 stipend. Interestingly, these stipends were not seen as salary, but rather as funds to help the women pay for whatever domestic arrangements would allow them to work part-time, and give them the opportunity, once again, to lead the life of the mind. [29] Lily had much in common with the other talented women who were her colleagues at the Radcliffe Institute. She, like most of the other women, was in her early thirties, she was the mother of young children—indeed, among them, the women that first year had a total of fifty-three children—and she had lost her place in academic life because of marriage and babies. [30] In September of that year, she moved into her office in the yellow Greek Revival house at 78 Mount Auburn Street (now home to the Harvard Society of Fellows) and threw herself into work—some last coursework towards her Ph.D., foundational research for a dissertation on Venizelos, and adult conversation with twenty-one equally extraordinary women who were lucky enough to be part of the same life-changing experiment.

Like all the women she was with, Lily used her stipend to maximize the number of hours she could work each week. A Newsweek article on the Radcliffe Institute reported that “while most of [the fellows] have used the money to hire additional help around the house…the most unusual expenditure… is that of Mrs. Lily Macrakis… She is using part of her $3,000 to pay for parking tickets so that she can spend an uninterrupted four hours each day in her stall at Widener Library without having to put another nickel in the meter every hour.” [31] In the same article Lily is quoted as saying “now that we’re here, we must succeed. It would be terrible if we just faded away after one year of work.”

One of Lily’s first official duties as a new Radcliffe Fellow was to accompany Constance Smith that fall to a meeting of the Junior League in Boston to spread the word about the Institute and raise money. Smith spoke to the women first, giving them some general background, and then had Lily, who had never spoken in public before, talk about her project and her new life as a part-time researcher. The audience was extremely hostile and spent a good half hour asking her questions like “Don’t you think that you are sacrificing the well-being of your children to your own ambition?” (Macrackis 1986:13). Lily had been nervous enough when asked to talk, but she was actually shaking by the time the Junior Leaguers were finished with her. And, in a 1961 interview of Lily commissioned by the Radcliffe Institute, Lily makes it clear that she, herself, constantly worried that the good women of the Junior League may well have been right. [32] Clearly, not just men, in 1961, were standing in the way of women with the kinds of ambitions and aspirations Lily had. But there were thousands of women who did want what Lily and the other fellows had been given. A story that appeared in the Manchester Guardian in January 1962 reported that two hundred women applying for night school at Northeastern University in the fall of 1961 had cited news of the Radcliffe Institute as the thing that inspired their return to school. [33]

Lily spent two years at the Radcliffe Institute, and during that time she finished the last of her Ph.D. coursework, [34] and she began research on Venizelos, which she would use both for her Ph.D. thesis and her published biography. As important, though, for the future, she gave the first research talk of her career to her fellow fellows. [35] Although she was extremely nervous, the talk was such a success that one fellow, Emiliana Noether, a professor of history at Regis College, asked her, on the strength of her presentation, to teach a course in Modern European history the following year at Regis College. With the encouragement, indeed the downright insistence of both her husband and Constance Smith, she taught her first undergraduate course at Regis during the second year of her fellowship. [36] To her complete surprise, she was not only good in the classroom, but she loved teaching. She was such a success that she was invited back the year after her fellowship ended to teach two more classes at Regis, and the year after that she was appointed Assistant Professor by Regis’s Department of History. By 1968, not only did she have tenure, but she was chair of the History Department, and would be chair for another twenty years. Both she and the people behind the Radcliffe Institute were ecstatic. A 1966 Radcliffe Institute report noted that out of the seventy-six women who had held Radcliffe Institute fellowships in the first five years of the program, twenty-seven now had part-time faculty positions and another twelve, including Lily, had full-time faculty positions. The report proudly noted that Lily, now a professor, had never even had an opportunity to teach before her time at Radcliffe. [37]

It is in 1968 that we finally find Lily equipped with the knowledge, the skills, the confidence and the academic position that would allow her to have such a successful career as an academic, a university administrator and a scholar. During her time at Regis, Lily would not only teach European history to hundreds of Regis undergraduates, but she would found a European Studies Program and a Greek Studies program at the college, and take two very lucky groups of students to Greece. During these years, she also played a central role in the Modern Greek Studies Association (MGSA), helping to bring the importance of modern Greek history, culture and literature to the attention of Greek and American scholars alike. She has often observed that over the course of a decade in the 1970s and 1980s she put in as many hours working for the good of the MGSA as she did in her full-time job as a professor and department chair. It is during these years that she helped organize and presided over a series of seminal conferences, including the all-important “Greece in the 1940s” symposium, held in 1978. The “splendid volume” that resulted from this meeting, according to reviewers was the “essential” work for any further study of the period (Iatrides 1981; Koumulides 1982:752).

In 1998, at an event held to celebrate Lily on her retirement as a Professor of History at Regis College, Sheila Megley, Regis’s president, spoke of Lily in a way that captures the qualities that have made her a force to be reckoned with:

Those of you who know Lily well, know that she has a tenacity that will not quit. She has a passion for truth, for seeking knowledge, for making connections, for revisiting ideas, for revising, rewriting, re-editing, and reworking. She has a passion for becoming, for loving, for learning, and for communicating. These passions define who she is and who she will become. [38]

Her words were prescient, because Lily, although ending her career at Regis, was about to become Academic Dean at Hellenic College, a position she would hold for nine years. At yet another retirement party, held in her honor at Hellenic College in 2010, her friend and successor, Demetrios Katos, described what Hellenic was like once she arrived: “New courses began sprouting all over the roster like wildflowers. Outdated curriculum? Revise it, she said…No study abroad opportunities? Start some!” [39]

Still, from the moment she arrived at Harvard until the day she retired from Hellenic College, she was always “an Athenian girl.” As Katos noted, on her first day at Hellenic College, she arrived dressed in “black leather pants.” [40]

Images

Figure 1: Lily and a school friend standing on the balcony of Chryssanthacopoulos home on Thiras Street, in Athens during the war.

Figure 2: Lily’s father (top row, second from the right) and her mother (bottom row, second from the right) with friends, ready for a night on the town during their first year of marriage.

Figure 3: Lily, sitting on the lap of her godfather, George Alevizopoulos. Behind, stands her dada.

Figure 4: Always the intellectual. The corner of Lily’s childhood bedroom, filled with her prize possession: books.

Figure 5: Lily’s sister Jenny in 1946.

Figure 6: Lily and Michael before their marriage.

Figure 7: “The Athenian girl” at Harvard in 1953.

Figure 8: Michael Macrakis’s great uncle, Mikhailos, a professional Cretan and Venizelist party boss in Iraklion in 1909 at Venizelos’s side.

References

de Ségur, S.C. 1858. Les Petites Filles Modèles. Paris.

Iatrides, J.O., ed. 1981. Greece in the 1940s: A Nation in Crisis. Hanover and London.

Koumulides, J.T.A. 1982. Review of J.O. Iatrides, Greece in the 1940s: A Nation in Crisis (Hanover and London 1981). Slavic Review 41:752.

Macrakis, A.L. 1992. Eleftherios Venizelos 1864–1910: The Making of a National Leader. Athens.

Macrakis, A.L. 1986. “Discovering Teaching as a Vocation.” Radcliffe Quarterly 72:13.

Milliex, R., ed. 1946. A L’école du Peuple Grec (1940–1944). Vichy.

Footnotes

[ back ] 1. All unreferenced information found in this essay is based on fifteen hours of interviews conducted in October 2009, further interviews in September 2011, or on the photographs and papers held in the personal collection of A.L. Macrakis. Further details of her life, not covered in the recent interviews, and which are referenced, can be found in the transcription of a long interview of Lily, undertaken in 1961, while she was a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute, and now housed in the Schlesinger Library (Schlesinger Library, Harvard University, RG XXVIII, Ser. 5.4, Box 7, “Macrakis, Aglaia Lily #8, hereafter referred to as “1961 interview”).

[ back ] 2. “1961 interview,” 8.

[ back ] 3. “1961 interview,” 9.

[ back ] 4. “1961 interview,” 14.

[ back ] 5. “1961 interview,” 3.

[ back ] 6. “1961 interview,” 12.

[ back ] 7. “1961 interview,” 13.

[ back ] 8. “1961 interview,” 17.

[ back ] 9. “1961 interview,” 20.

[ back ] 10. Lily’s mother actually knew Michael Sakellariou’s family as well, because he, too, was from Patras; and he later married Lily’s husband’s cousin.

[ back ] 11. “1961 interview,” 31.

[ back ] 12. “1961 interview,” 29.

[ back ] 13. “1961 interview,” 37.

[ back ] 14. “1961 interview,” 15.

[ back ] 15. “1961 interview,” 16.

[ back ] 16. “1961 interview,” 43.

[ back ] 17. “1961 interview,” 47–48.

[ back ] 18. “1961 interview,” 47–48.

[ back ] 19. “1961 interview,” 53.

[ back ] 20. “1961 interview,” 63.

[ back ] 21. Schlesinger Library, Harvard University, RG XXVIII, Series 1, Box 1, “The Institute for Independent Study, Radcliffe College, November 17, 1960.

[ back ] 22. Schlesinger Library, Harvard University, RG XXVIII, Series 1, Box 1, “Radcliffe Institute interim report,” July 15, 1962, 2.

[ back ] 23. Schlesinger Library, Harvard University, RG XXVIII, Series 1, Box 4, undated memo from Deane Lord to Constance Smith.

[ back ] 24. New York Times, November 20, 1960.

[ back ] 25. Schlesinger Library, Harvard University, RG XXVIII, Series 1, Box 4, undated memo from Deane Lord to Constance Smith.

[ back ] 26. New York Times, June 5, 1961.

[ back ] 27. The quote is written on the background notes used by the psychologist doing the interviews of Radcliffe Institute fellows that Lily took part in, in 1961 (Schlesinger Library, Harvard University, RG XXVIII, Ser. 5.4, Box 7, “Macrakis, Aglaia Lily #8).

[ back ] 28. Michael Macrakis was named for his great-uncle, Mihailos Macrakis, a professional Cretan nationalist and party boss for Venizelos in Iraklion. The family held an extensive collection of letters between Venizelos and Mikhailos and his brother Yiannis, Cretan cheiftains and Therisso fighters from Ayios Myron.

[ back ] 29. Schlesinger Library, Harvard University, RG XXVIII, Series 1, Box I, “Revised press release for the Friday morning papers of June 2, 1961;” and The Observer Weekend Review, January 14, 1962.

[ back ] 30. Schlesinger Library, Harvard University, RG XXVIII, Series 1, Box 6, “Data on fellows, 1961–66.”

[ back ] 31. Newsweek, “Women of talent,” October 23, 1961.

[ back ] 32. “1961 interview,” 70.

[ back ] 33. Manchester Guardian, Mary Shivanandan, “Mainly for Women,” January 19, 1962.

[ back ] 34. Not only did she receive a stipend, but Radcliffe paid for her tuition as well (RG XXVIII, Series 1, Box 6, “1961–1962 fiscal year”).

[ back ] 35. Schlesinger Library, Harvard University, RG XXVIII, Series 2, Box 1, “Seminar schedule 1962–1963,” and Series 1, Box 1, “Radcliffe Institute Interim Report,” July 15, 1962, p. 4.

[ back ] 36. Schlesinger Library, Harvard University, RG, XXVIII, Series 2, Box 1, “Former scholars 1961–1963 backgrounds and activities.”

[ back ] 37. Schlesinger Library, Harvard University, RG XXVIII, Series 1, Box 6, report of July 14 1966.

[ back ] 38. Regis Today (Fall, 1998), 25.

[ back ] 39. Demetrios Katos, “Lily Macrakis,” presented March 1, 2011, Hellenic College.

[ back ] 40. Katos, “Lily Macrackis.”