Introduction

1. Transliteration

2. Commentary

2. Translation

3. Analysis

καὶ Πληϊάδες, μέσαι δὲ

νύκτες, παρὰ δ’ ἔρχετ’ ὤρα,

ἐγὼ δὲ μόνα καθέυδω.

The moon has sunk,

and the Pleiades as well, and it’s the middle

of the night, time passes by

but I sleep alone.

The voice of the speaker, which is feminine, does not appear until the last line of this short poem. Up until this point, the poem has progressed by references to temporal markers in space: the moon, the Pleiades (which although mentioned are no longer visible), and then to specific constructs of time: “mid”-night, “hour”. The two verbs before the last line of the poem, δέδυκε and ἔρχετ’, are important in setting the scene. The first is a perfect with practically a stative sense: “the moon has now/is in a state of being set”; the second, however, is a processual or durative present: “time continuously/keeps passes[-ing] by.” The effect of these two lines is then completed by a sudden shift to the speaker of the poem (who turns out to be the focus), described as “sleeping alone.” The two parts of the poem, lines 1–3, and 4, only fit together insomuch as the last line serves as the semantic base for the preceding three lines. One must then infer that the time has all along been connected to the loneliness and sleeping of the woman, whose time it turns out to be. The time, therefore, does not exist outside the frame of reference of the speaker, which is only clear at the appearance of the speaker at the final gasp of the poem, which appears at the same time as it connects.

Up then, I want to make love with you,

In your smooth loins, as you come awake.

How sweet your caress,

How voluptuous your charms,

You, whose sleeping place wafts of aromatic and fennel.

O my loose locks, my ear lobes,

The contour of my shoulders and the opulence of my breast,

The spreading fingers of my hands,

The love-beads of my waist!

Bring your left hand close, touch my sweet spot,

Fondle my breasts!

[O come inside], I have opened my thighs!

(gap, fragmentary lines)

The use of the “I” in the poem would seem to be a simple voice, merely the woman in question, but as B. Foster notes, “she refers to herself in the plural in lines 1–13, but changes to the singular in line 14. Since this usage is otherwise attested of the goddess Ishtar, one may speculate that a goddess is speaking,” (B. Foster 2005:169). [3] This ability of the lyric “I” to transform itself into the voice of the goddess of love, Ishtar, is unusual in that the voice of the person is now simultaneously the human lover, and the goddess of love. This placement of the “I” within both the realms of mortal and divine emphasises the plea of the persona as both desirous and fulfilling that desire. This connection of absence with desire is also seen as a way of making the plea more real, as intensifying the action, and, lastly, of making the time of the poem ambiguous (and so more universal).

What is intriguing about this interruption is its ability to restructure the voices of the duet. Where in Egyptian love poetry the voices existed to complement each other, speaking in turn, the voices of the Song of Songs, can speak out of turn, representing a violation of the traditional model, but also emphasizing one voice over the other. In so doing, it, perhaps, allowed for the further interruption of one voice into complete silence, so to speak, as the duet faded into a monologue.

What is intriguing here is that both of these variations occur to the female voice; it is she who is interrupted and she who is refracted. Thus, she is essentially nothing or a multitude, having the capacity to be both absent and omni-present at once. The need for the one subsumed voice to have its reciprocation, in terms of desire, is then fulfilled by its relation to the female lover’s voice who speaks it (and eventually will gain her satisfaction). In terms of the variation we see later in Sappho, this adaptation and variability of the female voice seems to have had analogical models, which were then used by Sappho to achieve even more pronounced effects.

ἔμμεν’ ὤνηρ, ὄττις ἐνάντιός τοι

ἰσδάνει καὶ πλάσιον ἆδυ φωνεί-

σας ὐπακούει

καὶ γελαίσας ἰμέροεν, τό μ’ ἦ μὰν

καρδίαν ἐν στήθεσιν ἐπτόαισεν,

ὠς γὰρ ἔς σ’ ἴδω βρόχε’ ὤς με φώναι-

σ’ οὐδ’ ἒν ἔτ’ εἴκει,

ἀλλ’ ἄκαν μὲν γλῶσσα †ἔαγε† λέπτον

δ’ αὔτικα χρῶι πῦρ ὐπαδεδρόμηκεν,

ὀππάτεσσι δ’ οὐδ’ ἒν ὄρημμ’, ἐπιρρόμ-

βεισι δ’ ἄκουαι,

†έκαδε μ’ ἴδρως ψῦχρος κακχέεται† τρόμος δὲ

παῖσαν ἄγρει, χλωροτέρα δὲ ποίας

ἔμμι, τεθνάκην δ’ ὀλίγω ’πιδεύης

φαίνομ’ ἔμ’ αὔται·

ἀλλὰ πὰν τόλματον ἐπεὶ †καὶ πένητα†

He looks to me to be equal to the gods,

that man who sits across from you

and listens nearby to you speaking sweetly,

to you laughing charmingly; that, I vow,

makes the heart leap in my breast;

for when seeing you but a moment, speech fails me,

my tongue breaks, at once

a light fire runs beneath my skin,

my eyes are blinded, and my ears drumming,

the sweat pours down over me, and I shake

all over, sallower than grass:

I feel as if I’m not far off from dying;

but all is to be submitted and endured.

Sappho begins with the male, “he”, as does DM (“your masc. love”), but develops only the female voice. All other actors in the poem are subject to the gaze of the female beloved. Like the Song of Songs, the male and female are represented, along with a third, the competitor. Unlike the Song of Songs, however, the third actor, the other female, is the object of desire; it is she whom Sappho desires, and the male is merely a competing lover, insomuch as he is between the lover and the beloved. The voice is then refracted, as it were, to represent the other voices which are essentially voiceless in the poem. The female beloved and the male who is present with her, we can imagine from the earlier type, should have actually had speaking parts, but Sappho instead directs the listener to imagine the conversation between them. In fact, the male’s part has been completely deleted; at the moment of the female lover’s interference, it is only the female beloved who is reported to speak; the male is merely watching and listening. Like the Song of Songs, the voices which are acted out through the refraction of the female voice necessitate the reciprocation begged by desire, yet as there is only one voice in Sappho 199, that one voice is now entirely dependent upon this refraction in order to stress the reciprocation which it so desires. The use of ἴσος θέοισιν, which amongst the many other references it may have, may in fact be an old remnant of the “my lover is like …” formula which appears in both DM and the Song of Songs. If this is so, there is no doubt that this poem has a further layer, that of epic performance, where the phrase is also used, and which Sappho’s poetry could employ as a means of collapsing genres. Thus, if I am right to assume that DM represents the normal type for love poetry, a duet between female and male, seeing it as the deep structure of Sappho’s poetry reveals a unique insight into seeing the innovation within this genre which Sappho’s poetry displays, not just from a Greek perspective, but within a wider cultural frame.

in the dark,

Through all the long divisions of the night,

those hours

I, spendthrift, waste away alone,

and lie, and turn, awake ‘til whitened dawn.

And with the shape of you I people night,

and thoughts of hot desire grow live within me.

What magic was it in that voice of yours

to bring such singing vigor to my flesh,

To limbs which now lie listless on my bed without you?

Thus I beseech the darkness:

Where gone, O loving man?

Why gone from her whose love

can pace you, step by step, to your desire?

No loving voice replies.

And I (too well) perceive

how much I am alone.

Intriguingly, J. Foster has removed all traces of the male beloved, and focused solely on the female. In addition, the long catalogue of comparison of the beloved to various objects which comes in the following stanzas, and practically for the remainder of the female lover’s part, is also deleted. What remains is what was seen, perhaps, by him to be the most poignant, and the most resonant. Is this the way in which the love poem traveled from one culture to the other? Is this how the female voice was able to be adapted so easily (to say nothing of the male-dominated societies in which it existed)? What caused him to innovate this poem to such an extent? The largely fragmentary nature of DM, as seen above, may have been a factor as well. In that case, is the need to understand, to piece together a coherent whole, (which could have been the case in a song culture which was multicultural and multilingual), allow one to draw from the depth of similar human experiences to achieve that semantic whole? I feel that the answer to this question goes part and parcel with the answer to the questions at large in this paper. It seems, then, that the (re)performance of poetry, as with J. Foster’s translation of DM, may prove to be a better example of how this phenomenon of cultural exchange works when there is so much that is irrecoverably fragmentary.

4. Lingering Questions

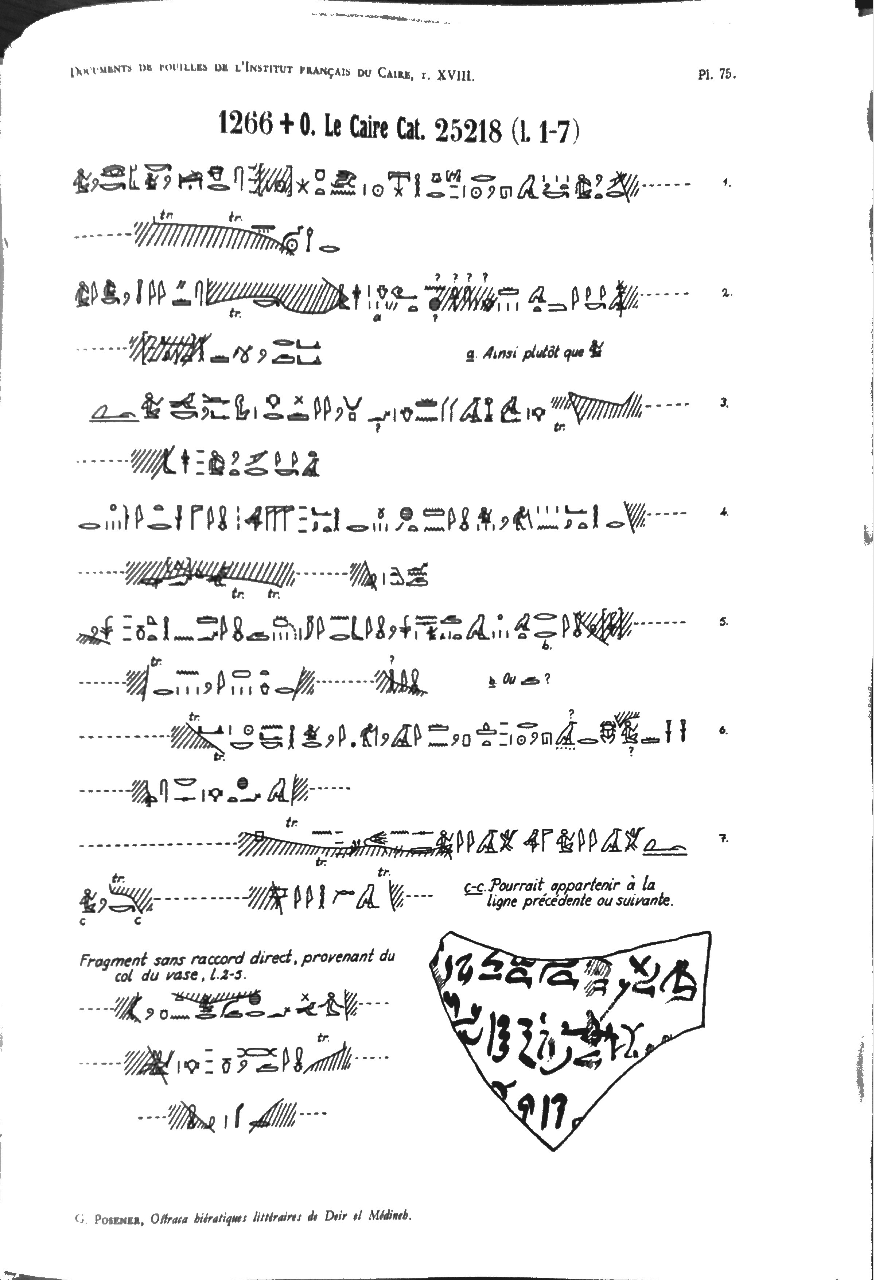

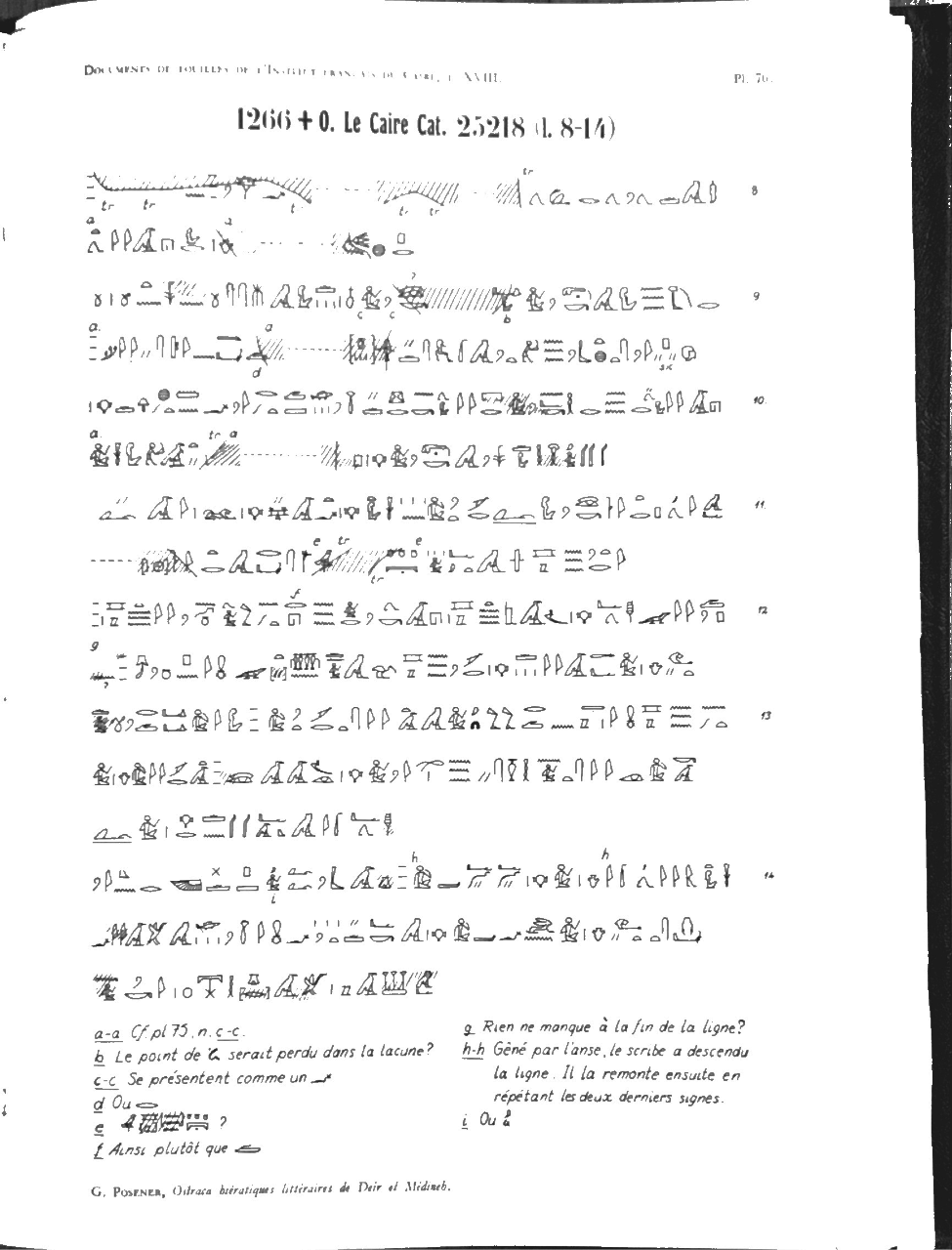

Appendix 1: Hieroglyphic Transcription (Posener 1972)