Introduction

1. New Testament Titles

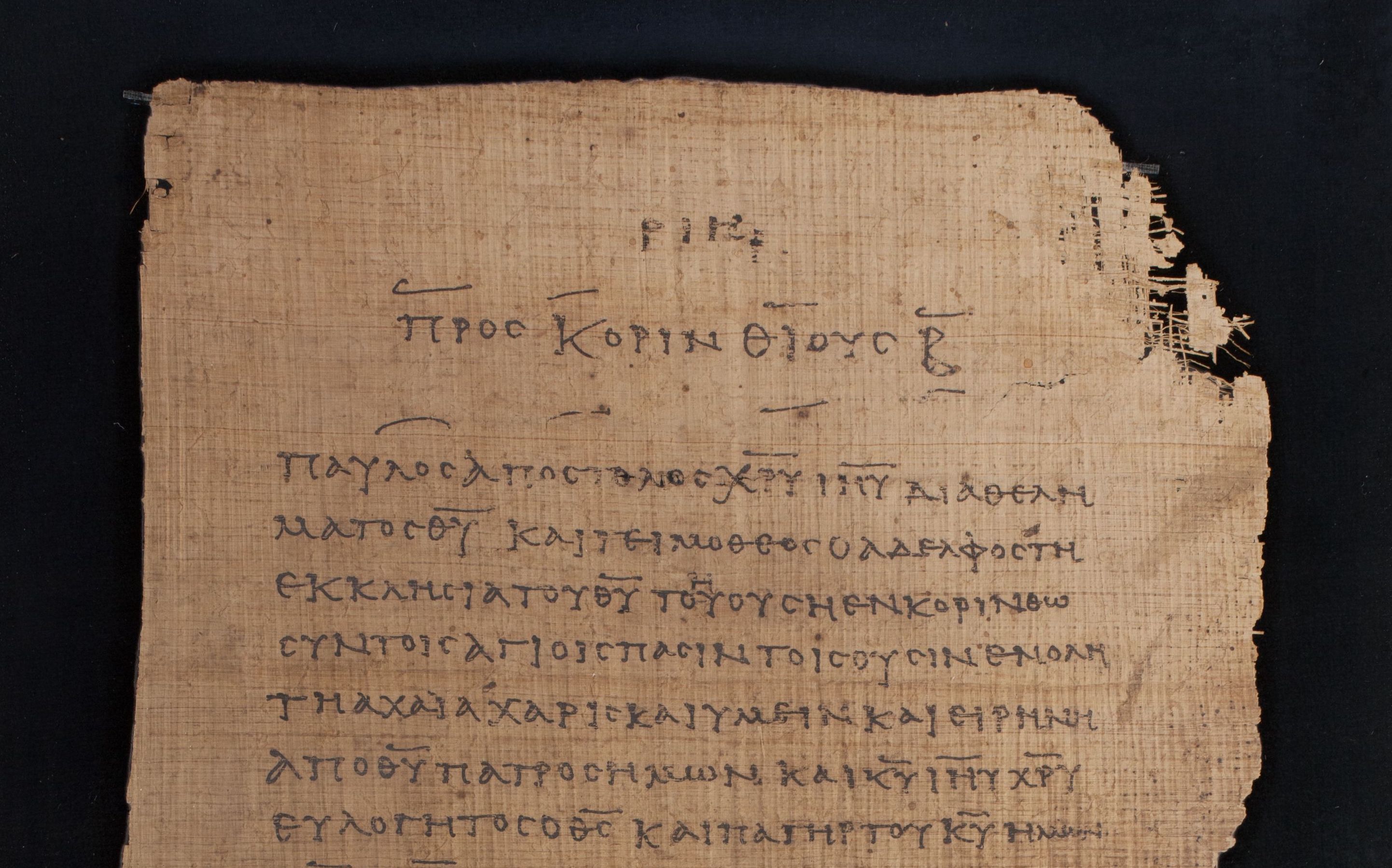

But what exactly are we looking for when we speak of titles? Within the context of the NTVMR, the first forms of the title that the TiNT project seeks to gather data on are inscriptions and subscriptions. These constructions are the most common titular form in the New Testament’s Greek tradition. The inscription is readily familiar to those who read modern Bibles or other books. The inscription to 2 Corinthians, for example, in CBL BP II (Figure 1), perhaps the oldest extant copy of Paul’s letters, is προς κορινθιους β, a formulation that could easily be glossed in English as “To [the] Corinthians 2” or 2 Corinthians. It is situated here between the page number and the start of the text of the letter and is set apart from the main text by its slightly larger script size and the use of intermittent horizontal lines above and below the title. TiNT will aggregate not only the text of this formulation, but these other design features that distinguish the title aesthetically from the text of the work it heads.

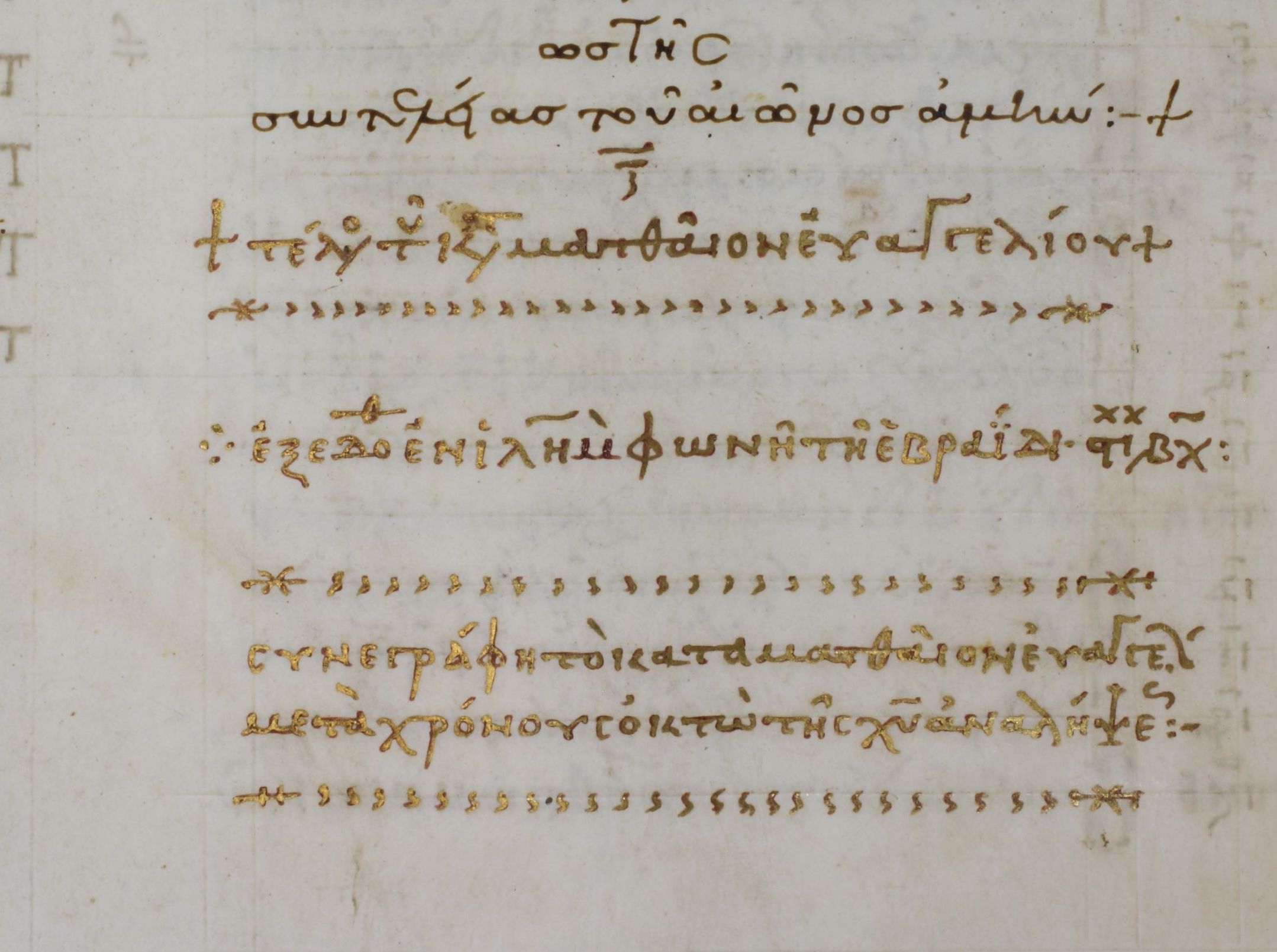

Setting aside the peculiarities of TCD MS 30’s production, subscriptions are also common in Greek New Testament manuscripts, although less familiar to readers in modern print cultures. Not only do these items discriminate between literary works aggregated within a codex, but they also often reiterate, sometimes inexactly, the title of the inscription. For example, the inscription and subscription of Paris, BnF Coilsin gr. 205 (GA 93; diktyon 49345) differ slightly in Revelation: “Apocalypse of John the Theologian” (ιωαννου του θεολογου αποκαλυψις) in the inscription and “Apocalypse of St John the Theologian in the subscription (αποκαλυψις του αγιου ιωαννου του θεολογου). The difference in this instance is not earth-shattering, but it is part of a larger network of fungible titular formulations, which are pliable not only in terms of text, but of positioning, layout, and artistic emphasis. In some cases, the subscription also provides further information on the work, often drawn from commentary or other interpretive traditions. The subscription to Matthew in Dublin, CBL W 139 (GA 2604; diktyon 13571), an early twelfth century Gospel codex, is one example (Figure 2).

τελος του κατα ματθαιον ευαγγελιου

εξεδοθ(η) εν ιλημ φωνη τη εβραιδι

συνεγραφη το κατα ματθαιον ευαγγελιστη

μετα χρονους οκτω της χυ αναληψεως

End of the Gospel according to Matthew

Published in Jerusalem in the Hebrew languages

Written by Matthew the Evangelist eight years after Christ’s Assumption

At the end of this work, three declarative statements are set off from the main text by the use of gold ink, slightly larger script, and strings of non-alphabetic glyphs. The first reiterates the title of the work and signals the work has ended, the second identifies in place and language of composition, and the third identifies its putative author (the governing voice of the canonical gospels is anonymous) and the date of composition. There is an ongoing debate in biblical studies about which parts of this formulation actually qualify as a title—some distinguish between the titulus finalis (the first line) and the subscription (lines 2–4)—but we treat this entire formulation as a title because its aesthetics and positioning coalesce to signify a unified paratextual feature within the manuscript.

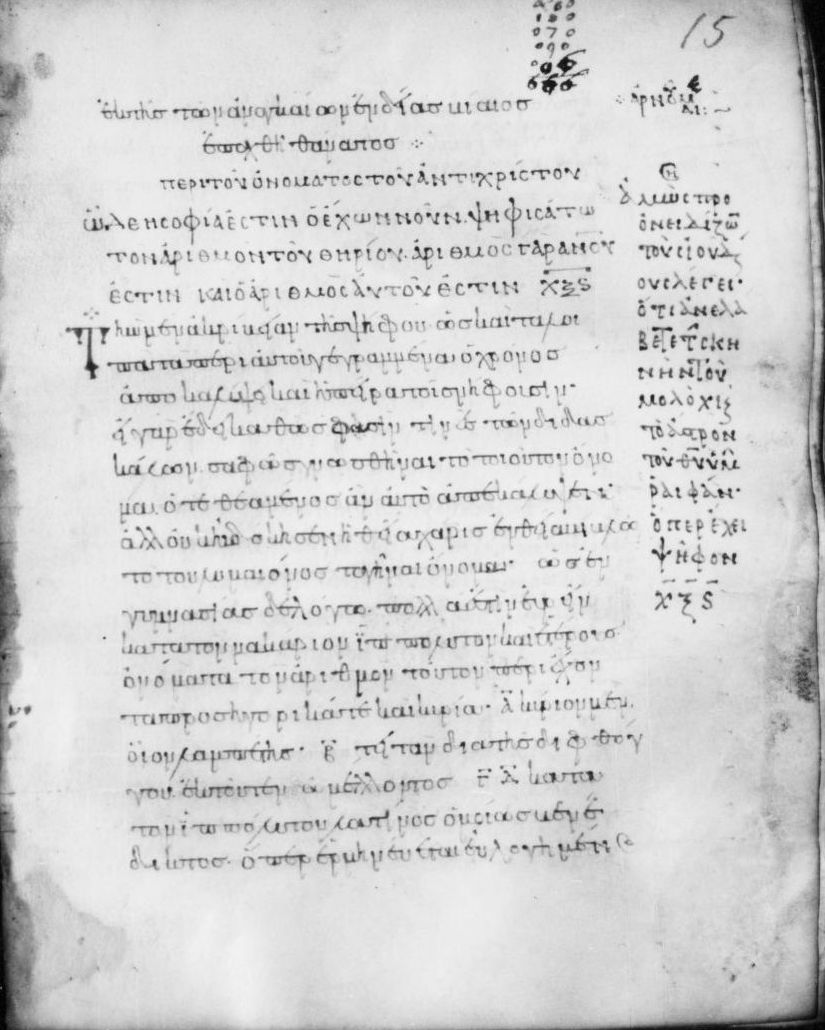

For example, Athos, Pantokratoros, 44 (GA 051; diktyon 29603), a tenth-century copy of the Andrew of Caesarea commentary on Revelation, includes the titles for each of the seventy-two textual segments (kephalaia) into which Andrew divided the Apocalypse. The folio that preserves Rev 13:18, the famous number of the beast passage (15r, Figure 3) contains a number of paratexts, including a lengthy marginal comment connecting the identity of the beast to the figure Raiphan mentioned in OG Amos 5:26, an attempt to do the calculation of the number of the name in the top margin, a short note to “deny me” (ἀρνοῦ με) referring to the antichrist, and a page number added by a later hand. There’s a lot going on here, but the third line of the text is an intertitle that describes the perceived content or significance of the scriptural text (lines 4–6), which is written in an uncial script compared to the commentary that is written in minuscule. The title (line 3) reads “Regarding the Name of the Antichrist” (περι του ονοματος του αντιχριστου), a formulation that directly reflects Andrew’s interpretation of the beast as an eschatological antagonist. The term “antichrist” is not used in Revelation, and Andrew’s interpretation stands starkly against the conclusions of modern scholarship that see this figure and his paronomastic name as a cipher for a historical Roman emperor, perhaps Nero. [14] This titular formulation cues readers to adopt Andrew’s eschatological perspective and to continue to attempt to decode the name of the figure by adding the numeric value of Greek graphemes. Notably, this process continued into the late and post-Byzantine period, where some commentators identify Muhammad as the beast because the graphemes of one form of his Greek name (μοαμετις) and the spelling of Mecca in Greek (μαχκε) equate to 666. [15] Intertitles influence the deployment of reading protocols and processes of interpretation, and they represent another complicating factor for the editing of this material. It may not ultimately be feasible to capture every intertitle in every manuscript, but we intend, at the very least, to focus our attention on intertitles for a particular set of New Testament works, perhaps the Catholic Epistles. [16]

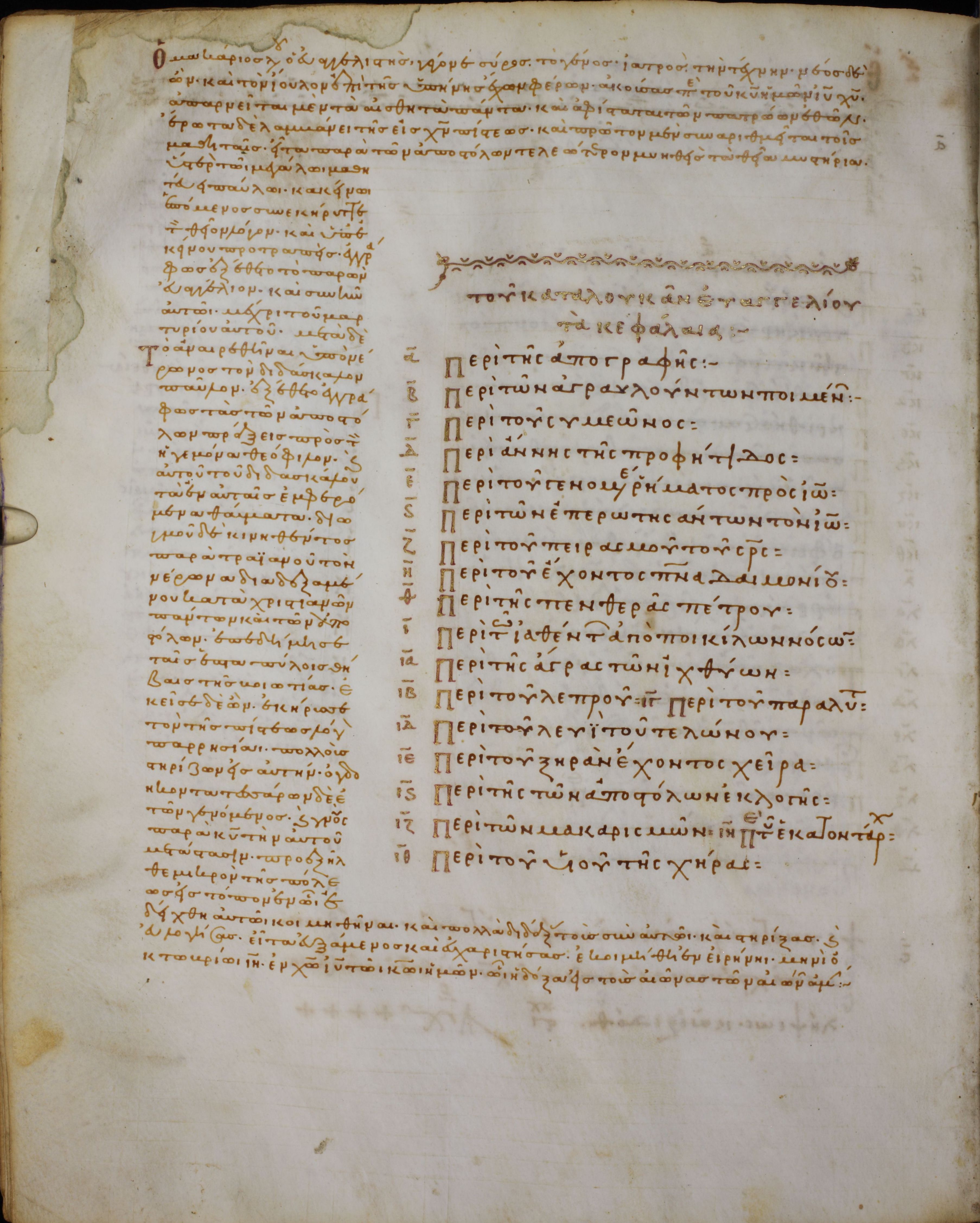

These kephalaia that sometimes segment the text of manuscripts are also regularly collected in tables of contents (pinakes). For example, each of the four gospels in CBL W 139 (GA 2604) are prefaced by tables of contents (and other paratextual prefatory texts) that enumerate the titles of each of the identified textual segments. The pinax that precedes Luke (178v–180r, see Figure 4) is bounded by a hypothesis to the gospel and a lexicon of Hebrew words (179r) and it contains chapter number and title of each of Luke’s eighty-three chapters. The table itself is entitled (“The Chapters of the Gospel according to Luke,” του κατα λουκαν ευαγγελιου τα κεφαλαια) and each entry in the table is a titular formulation that functions as such when it appears in the text. Because most of the titles that appear in the tables are fairly stable in terms of wording, we can build templates for most instantiations and edit them to match the text of the images when necessary. But this complexity of the titular tradition calls for greater flexibility in our editorial tools, data querying, and recall, particularly if we want to link the appearance of an intertitle in a pinax with its appearance among the main text.

2. TiNT Project Digital Workspaces and Other VRE Models

Designing a digital workspace that allows scholars to develop research hypotheses and to explore the richness of the collected manuscripts presents a number of challenges. Researchers in ADAPT have addressed aspects of these challenges in previous digital humanities projects, a track record that informs our approach to developing digital editorial tools for TiNT. A good example is the CULTURA project. [20] CULTURA was a European Commission funded project that ran between 2011 and 2014. It employed personalisation to support the exploration of digital collections (primarily Irish archival manuscripts and other historical sources), the collaboration of users around these collections, and to understand users’ interests in external digital archives with similar content. The CULTURA VRE pioneered the development of next generation adaptive systems that provide new forms of multi-dimensional adaptivity, including:

- personalised information retrieval and presentation which respond to models of user and contextual intent;

- community-aware adaptivity which responds to wider research community activity, interest, contribution, and experience;

- content-aware adaptivity which responds to the entities and relationships automatically identified within the artefacts and across collections;

- personalised dynamic storylines which are generated across individual as well as entire collections of artefacts.

CULTURA advanced and integrated the following key technologies to meet these goals:

- cutting edge natural language processing, which normalises ambiguities in noisy historical texts;

- entity and relationship extraction, which highlights the key individuals, events, dates, and other entities and relationships within unstructured text;

- social network analysis of the entities and relationships within the content, and also of the individuals and broader community of users engaging with the content;

- multi-model adaptivity to support dynamic reconciliation of multiple dimensions of personalisation.

The CULTURA VRE offered users features that enabled them to move seamlessly between four phases of engagement with the materials available: Explore, Support, Guide, and Reflect. These phases have been discussed in detail in another context, [21] but we reiterate them here to show their relevance for the editorial and research agenda of TiNT.

- Explore. In CULTURA, users are offered a range of knowledge-informed exploration features that enable them to examine the entities and metadata features of manuscripts. This allows them to describe the facets that are of relevance to their enquiry. For example, users could express what they are looking for through faceted search dialogues, which supported free and autocomplete text. In the context of TiNT, searchable features may include location on page, style, pigments chosen, and many others. These facets can be supplemented with keyword and entity search to allow users to refine their search protocols. Items discovered could be grouped into projects allowing users to have several parallel explorations. This would allow users to have several concurrent explorations ongoing with resulting documents gathered. Importantly, the historical situation that led to their being gathered would also be captured.

- Support. Recommendations for similar items were included in CULTURA. This allowed scholars to access metadata, textual, and entity similarities even if they did not explicitly search for this material, a process that may lead to new connections between objects. An example of this may be seen in Figure 5.

In TiNT, additional metadata features such as aesthetic considerations could also be factored into such recommendations. Users in CULTURA could control the criteria for recommendations. For example, they could mark a recommended item as not applicable and set the reasons, allowing them to identify which metadata elements led to the match and why. This allowed users, in the scope of a project, to tailor how the system functioned. The various textual, aesthetic, and layout features captured in the TiNT project can function in similar ways.

- Guide. The CULTURA project was designed with non-expert users in mind and allowed a set of manuscripts to be presented as a narrative sequence to users with expert commentary. This commentary could tie into specific entities and metadata, as well as highlighting parts of the text, enriching user guidance for searches. The vision was that such non-expert users could still leave the guidance to explore and be supported in whatever topics piqued their interests. This commentary was represented in a widget alongside the content the user was examining. Even though the data that the TiNT project produces is intended primarily for experts, it could also be arrayed in a narrative fashion. Or, alternatively, project metadata could be used in such a way as to orient users of the database toward the critical questions central to the project’s goals or other lines of enquiry. Part of the process of creating a public, searchable database for the project data is to experiment with these possibilities.

- Reflect. Finally, reflect offers users the ability to see what models CULTURA was constructing of their interests. Their interactions with manuscripts, including searches and clicking of entity links, were implicitly modelled to determine which metadata features and entities they were showing the most interest in. This model was available for users to both scrutinize and control their interactions with the data, pruning unwanted elements and adding others. This gave users the ability, within the context of a project, to further refine and control what was of specific interest to them, informing the system’s support recommendations and offering unique opportunities for self-reflection within the context of engagement with artefacts. Constructing a reflect tool within TiNT’s database will give users opportunities to refine their approach to the material. Of course, before this feature of the database can be built, the project must first gather the requisite data, which will be produced using the project editorial tool embedded in the New Testament Virtual Manuscript Room (see below).

CULTURA offers several examples of how different phases of research and hypothesis generation may be supported, particularly over complex and rich metadata-described content. This has direct relevance to TiNT as users explore the rich diversity of titles across a variety of collections.

As obvious as it may seem, the structure of the knowledge graph itself should be such that it is possible to respond to the kinds of queries we anticipate will be executed over our triples. During these early stages of development, we have performed an information-gathering task by asking historians to submit “competency questions,” which they believed would be asked of the knowledge graph. Examples of competency questions elicited from the subject matter experts for Beyond 2022 include:

- “Are there Birth/Death/Marriage Records in Dublin in 1954?”

- “Who was the Bishop of Galway in 1882?”

- “Were there any [surname] within 20 miles of [place] just before the famine?”

For the knowledge graph, we adopted and extended the Web Ontology Language (OWL) implementation of the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (CRM) [24] because it was considered to be the most appropriate to meet the needs of the project. The historian generated spreadsheets (e.g., for people and places) are stored as Comma Separated Values (CSV) files and transformed into a Resource Description Framework (RDF) graph representation via R2RML, [25] a W3C Recommendation to transform relational data into RDF via a set of mappings. We avail of R2RML-F, [26] which allows us to access the CSV files as relational databases. The generated mappings prescribe how the data contained in those spreadsheets should be transformed into entities and relationships according to our CIDOC-CRM ontology. In later phases of the project, historians will gather and compile CSV files from other sources (e.g., historical census data), which need to be transformed into RDF according to the same ontologies. The use of R2RML thus allows for a scalable and declarative ingestion pipeline. If TiNT adopts a knowledge graph approach to model interconnections between entities (e.g., people and places) to aid scholarly exploration and knowledge discovery, then adopting a similar approach where declarative standards-based R2RML mappings are used to manage and control the ingestion of information into the knowledge graph (perhaps by independent actors or NLP processes) can benefit from the experience of Beyond 2022 project.

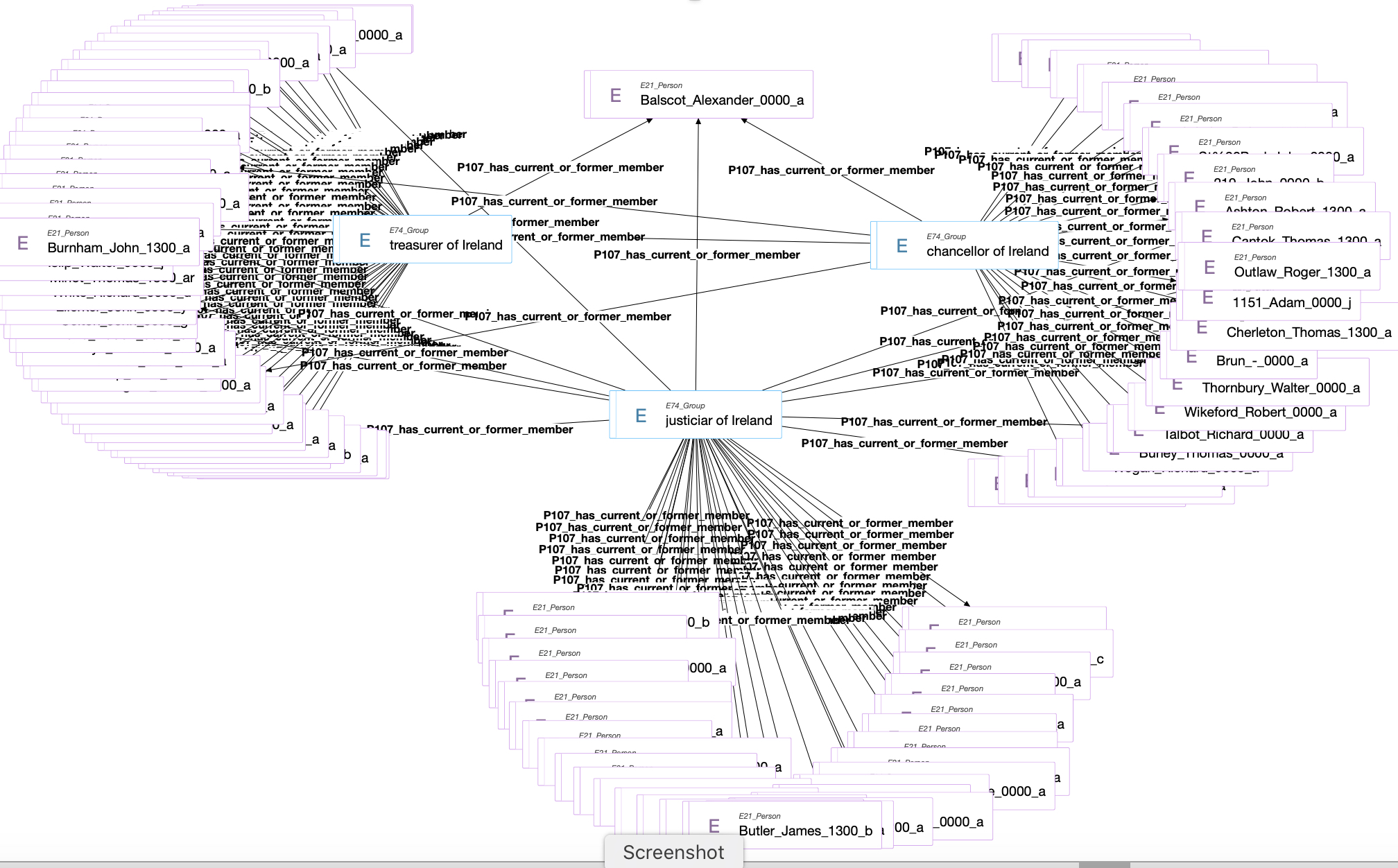

Historians in Beyond 2022 have already seen how one can easily discover the people associated with certain offices (e.g., “chancellor of Ireland”) and the overlap between different offices using Ontodia. In Figure 6, we demonstrate how one can discover people that have filled several positions, with one person being associated with all three, in this case, a certain Alexandre Balscot. [28] The URI of that person can then be used to retrieve a page with additional historical information. [29] Tools like these allow subject matter experts (and other users, for that matter) to discover information that might have taken a lot more time going through manuscripts.

3. The TiNT Project’s Editorial Tool

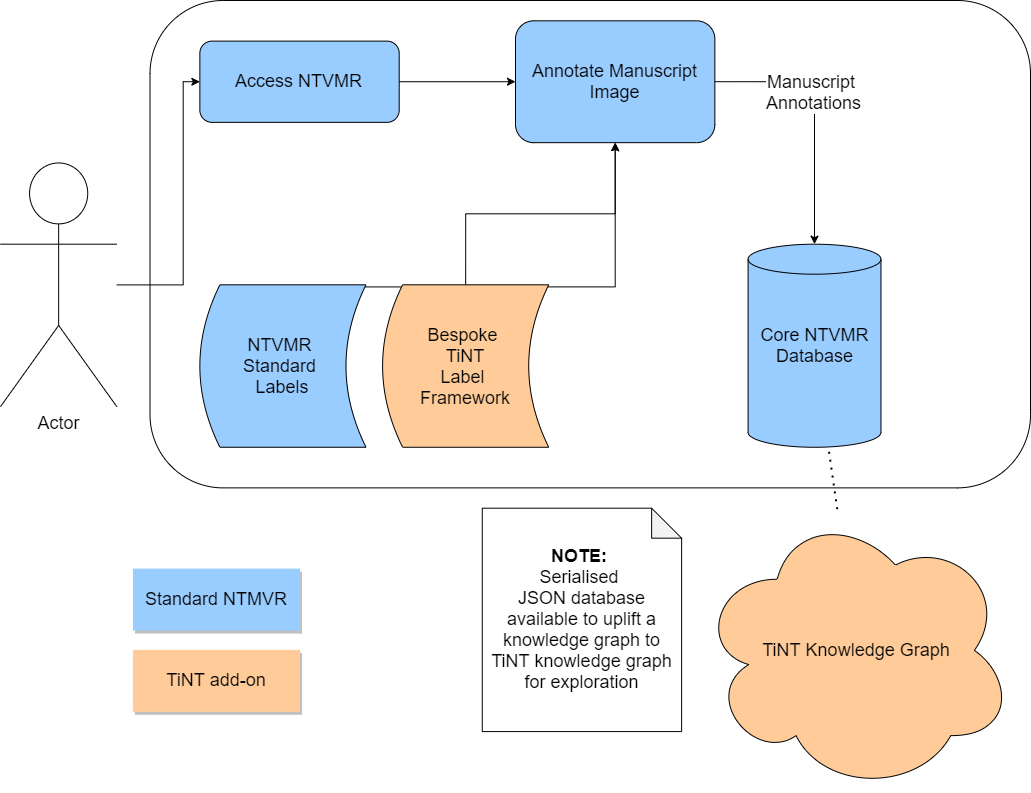

As part of the TiNT project, the ADAPT Centre has been tasked with enhancing the NTVMR editorial tool to better enable archivists’ enrichment of digitalized manuscripts specifically required for this project. The NTVMR already includes functionality to directly add new tags and labels by hardcoding in new label fields. The TiNT project specifies eight high-level information labels with several further nested subcategories. For instance, Title Type includes options for Inscription, Final Title (titulus finalis) and further nested specifications within each option for prologue titles, subscription titles, etc.

This editorial tool is key to the data gathering aspect of the TiNT project, and its relationship to the larger NTVMR VRE and the details of its information labels and their subcategories continue to develop. Nonetheless, this model for data aggregation and retrieval enables efficient editorial engagement with manuscript images and builds a unique set of information that can inform the critical studies of the TiNT project’s core team members. It is clear that for the TiNT project to meet its stated critical goals there must continue to be close cooperation between philologists, computer scientists, and developers, as well as between institutions and academic centers. (The shared authorship of this article is clear evidence of this reality.) To this end, we hope that this article has laid the groundwork for future collaboration, especially the further development of digital tools for TiNT and the continued growth of the NTVMR as a VRE devoted to the study of the New Testament’s Greek manuscripts in all their dimensions.