0. Lexicology and Textometry

1. Textometry and Latin Databases

Today, the LASLA Classical Latin database has reached about 2,500,000-word forms and is aiming to involve, one day, the entire classical Latin literature—from Plautus to Apuleius. In addition, the LASLA team is working on some later texts—such as the Historia Augusta—and has already analyzed a large corpus of Late and Medieval Latin Hagiographical texts. In order to allow textometric studies of this corpus, LASLA has developed a joint project with the UMR 7320: “Bases, corpus, langage” at the Université Côte d’Azur (CNRS). Both laboratories adapted together the new Hyperbase Web Edition platform to handle the LASLA Latin files, distributed in various databases—a general one with all the LASLA files, another with the major works, and several corresponding to various genres or authors. The Hyperbase-L.A.S.L.A. Web Edition (http://hyperbase.unice.fr/hyperbase/?edition=lasla) allows not only documentary mining but also statistical research. The user can perform searches on any word form, lemma, morphological tag, syntactic tag or string consisting in a combination of word forms, lemmas and tags—with, if needed, gaps between the units of the string. From a statistical point of view, Hyperbase allows numerous forms of statistical research—reduced deviation, tree-analysis, correspondence analysis—not only on the distribution in the corpus of all the above-mentioned items but also on their collocates. As far as the semic analysis is concerned, distributions of words belonging to the same semantic field can already be instructive, as illustrated by Figure 1. According to this distribution histogram, the lemma supplico appears to be characteristic of Plautus and some of Cicero’s speeches. On the contrary, the lemma precor is mainly found in poetry and tragedies. This seems to indicate a specialization of the two lemmas related to text genres. However, such a distribution histogram does not allow pinpointing, which semantic features of the two lemmas can explain this specialization. With this aim in view, we have to use a more sophisticated method, relying on the analysis of the specific collocations of both lemmas.

2. Latin Lexicology and Specific Collocations

3. Specific Collocations with Hyperbase Latin

These two examples show that the method applies successfully not only to concrete words but also to abstract words. Two other cases will exemplify the various search possibilities offered by Hyperbase: the case of uirtus and that of teneo.

4. The Virtus Case

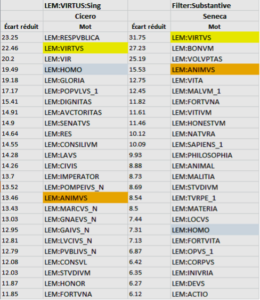

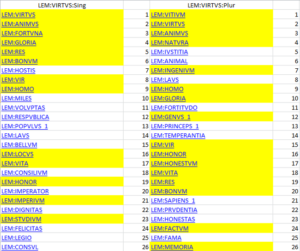

As we also know from modern languages—such as, “liberty” versus “liberties”—it is sometimes necessary to distinguish between the singular and the plural forms of a word to establish its various definitions. As Hyperbase allows choosing a lemma associated with a tag as “pivot,” it is easy to study collocates of the singular and plural forms of the same word. The behavior of the word uirtus is, in this respect, particularly exemplary, as shown in Figure 3.

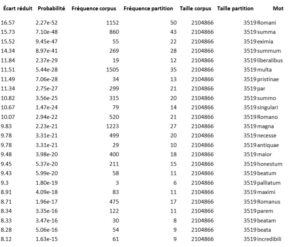

The study of adjectives functioning as collocates of uirtus is also very instructive. We have used a text span of three tokens in order to study specifically the adjectives preceding or following the occurrence of uirtus (Figures 4 and 5). We have only taken into account adjectives that can agree with the feminine singular. The results for the specific collocates of the singular forms of uirtus—summa, eximia, multa, pristina, par, magna, antiqua, singulari, maior, beata, incredibili—are consistent with what we noticed for the substantives. For the plural, the list of adjectives likely to agree with uirtutes, uirtutum, or uirtutibus is more limited and more general: pares, ceterae, grauissimae, and similes are all adjectives used to compare one uirtus to others, which means that the plural use stays in the philosophical domain.

uirtus.

It is also clear that the singular uirtus, which is related to public life and war, and the plural uirtutes, which have a philosophical meaning, do not appear in the same text types. However, we wonder in what kinds of text the singular uirtus does appear and if it is always endowed with the same meaning. A study of the distribution of the singular forms of uirtus (Figure 6) shows that uirtus is not only characteristic of historians, such as Caesar and Sallustius, but also, especially, of Cicero and Seneca.