1. Introduction

2. Genitive Absolute—How Is It Used and Is It Always Absolute?

Let us begin by examining how the GA construction is defined by the Encyclopedia of Ancient Greek Language and Linguistics (Buijs 2013):

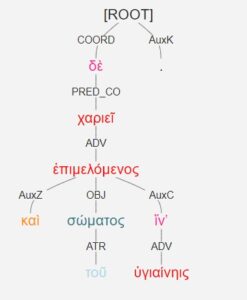

In other words, we are talking about a participial phrase that is independent of the structure of the main clause or the rest of the sentence. [3] It is an optional constituent, and many grammars discuss it within the section of circumstantial participles. An example is from Isocrates 9.56:

The recently published Cambridge Grammar of Classical Greek defines the GA as, “When the subject of the participle is not a constituent of the matrix clause, it must be expressed separately. In this case, both the participle and its subject are added in the genitive case.” It supplements this definition by noting that occasionally the subject is not expressed if it can be easily supplied from the context. [4]

When studying the postclassical Greek featured in documentary papyri, one should always consult Mayser’s grammar. According to Mayser, the GA does not retain all its spectrum in Koine Greek. He also makes the important observation that in papyri, it is used most often in a way that would be unacceptable in Classical Greek and rare in the New Testament (NT); that is, the subject of the GA and the matrix clause coincide. [9] One example from Mayser, which is also in our corpus, is P. Cair. Zen. 2 59245, 1:

Here, the genitive absolute construction has the first-person singular pronoun (μου) as the agent—the subject of the absolute construction. However, the matrix clause predicate is also in the first-person singular (κατέλαβον) and refers to the same person. In Classical Greek, one would instead expect a circumstantial participle in the masculine singular nominative (ἀπελθών) to agree with the subject of the matrix clause predicate (participium coniunctum).

3. Parsed Corpora and Querying

3.1 AGDT

3.2 Gorman Trees

3.3 PapyGreek

3.4 Queries in Kiln Platform

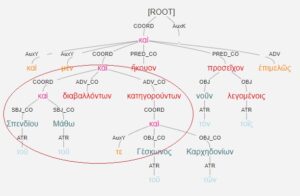

When querying treebanks for any feature, a major challenge is traversing the tree’s structure to find dependencies between the words. In the standard treebank XML structure, these are recorded through the @id and @head attributes, representing respectively the word’s place in the sentence in word order and its immediate governor. Often, however, we are not interested in the head—i.e., in the immediate parent element—of a given word (in cases of coordination, for example) but in the ancestors. Therefore, as a first step in preprocessing the document for querying, the XML is restructured to more closely represent the actual tree hierarchy by making the head ‘word’ parent elements of their dependents. This disrupts the linear structure of the XML and takes advantage of the possibility to query directly using the ancestor-dependent axis, without the need to check each time the words @id and @head to establish the dependency relations between them (see Figure 3).

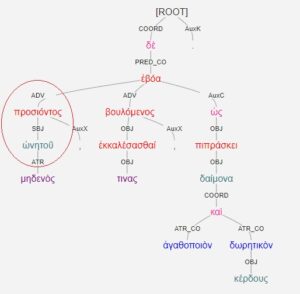

Having standardized and restructured the XML documents, we created additional annotations in order to make the phenomenon more easily discoverable. In devising the query process for genitive absolute constructions, we, first and foremost, had to establish rules regarding the possible configurations of dependencies between the participants in a GA construction within the treebanking framework. As a circumstantial participle, the head of the GA is marked with the syntactic label ADV, and its morphological analysis contains the information that it is a verb, participle, and in the genitive case. Its required dependent is the subject of the participle and is marked with syntactic label SBJ; the only morphological requirement needed is the genitive case. [33] Since the participle and the genitive agent can participate in ‘direct parent’-‘direct child,’ ‘indirect ancestor’-‘indirect dependent’ relations, or, if a coordinator is involved, even be ‘sibling’ elements, “valid paths” were defined from each component of the construction to each other participant, with coordinators factored in as possible “bridges” between them (see below examples of the four different types). Each word satisfying the morphological requirements and able to reach another potential participant in the construction through a valid path of dependency is given a @group attribute, the value of which is taken to be the value of the @id of the first genitive agent in word order (see Figure 4).

4. Parsed Corpora and Genitive Absolute

4.1 Overview

In this section, we will examine the use of the GA construction in two—partly overlapping—corpora of treebanked Ancient Greek literature and then compare the results with our treebanked corpus of Greek documentary papyri. First, some general counts from these corpora in Table 1.

| Counts | AGDT | Gorman | PapyGreek: orig (reg) |

| 1. Tokens (all) | 321829 | 605779 | 44309 (44098) |

| 2. Tokens (minus punctuation, gaps, artificial tokens) | 281675 | 540438 | 37215 (37283) |

| 3. Sentences | 18417 | 25731 | 3102 (3103) |

| 4. Sentences with GA | 1200 | 2773 | 131 (142) |

| 5. Total number of GA | 1427 | 3338 | 189 (210) |

| 6. % of sentences with one or more GA (of all sentences) | 6.52 | 10.78 | 4.22 (4.58) |

| 7. % GA / Number of sentences | 7.75 | 12.97 | 6.09 (6.77 ) |

| 8. % GA / Number of all tokens | 0.44 | 0.55 | 0.43 (0.48) |

4.2 Genitive absolute in the literary corpora

When we study the appearance of the genitive absolute construction in the AGDT and Gorman corpora author by author, it is clear that epic and tragedy have the least number of occurrences (see Table 2). This indicates that the genitive absolute was seldom considered to be a suitable linguistic construction in elevated, orally delivered poetry. It would be a stretch to say that it speaks directly to its use in spoken language.

| Author, (AGDT corpus) |

1. Tokens | 3. Sentences | 4. Sentences with GA | 5. Total number of GA | 6. % of sentences with one or more GA | 7. % GA / Number of sentences |

| Aeschylus | 48449 | 3958 | 45 | 46 | 1.14% | 1.16% |

| Hesiod | 19284 | 1183 | 20 | 22 | 1.69% | 1.86% |

| Ps-Homer | 3968 | 255 | 5 | 5 | 1.96% | 1.96% |

| Sophocles | 50094 | 4001 | 53 | 55 | 1.32% | 1.37% |

The second group to be taken as its own entity is formed by the orators or rhetorical writers of the classical period. Some stylistic variations can be observed: for example, Demosthenes favors the GA much more than other authors (see Table 3). As rhetorical texts were also meant to be orally delivered, their use of the GA indicates that it was considered a possible, although not common, spoken feature in the courtroom.

| Author, date (Gorman corpus) | 1. Tokens | 3. Sentences | 4. Sentences with GA | 5. Total number of GA | 6. % of sentences with one or more GA | 7. % GA / Number of sentences |

| Antiphon, 5th BCE | 16433 | 764 | 49 | 52 | 6.41% | 6.81% |

| Lysias, 5th/4th BCE | 22122 | 971 | 63 | 73 | 6.49% | 7.52% |

| Demosthenes, 4th BCE | 58038 | 2134 | 223 | 281 | 10.45% | 13.17% |

| Aeschines, 4th BCE | 15971 | 678 | 36 | 41 | 5.31% | 6.05% |

We will now turn to the documentary papyri to provide a picture of the Hellenistic and Roman periods.

| Author, date (Gorman corpus) | 1. Tokens | 3. Sentences | 4. Sentences with GA | 5. Total number of GA | 6. % of sentences with one or more GA | 7. % GA / Number of sentences |

| Aesop (AGDT) | 5221 | 366 | 44 | 47 | 12.02% | 12.84% |

| Ps.-Xenophon, 5th BCE (Gorman) [36] | 3723 | 170 | 4 | 4 | 2.35% | 2.35% |

| Herodotus, 5th BCE (Gorman/AGDT) [37] | 33150/33102 | 1555/1555 | 132/134 | 154/156 | 8.49%/8.62% | 9.9%/10.03% |

| Thucydides, 5th BCE (Gorman/AGDT) | 32344/25266 | 1204/942 | 124/101 | 151/127 | 10.3%/10.72% | 12.54%/13.48% |

| Xenophon, 4th BCE (Gorman) | 57903 | 2811 | 175 | 205 | 6.23% | 7.29% |

| Plato, 4th BCE Apology (Gorman) | 10457 | 481 | 17 | 20 | 3.53% | 4.16% |

| Plato, 4th BCE Eythyphro (AGDT) | 6349 | 426 | 5 | 5 | 1.17% | 1.17% |

| Aristotle, 4th BCE (Gorman) | 19867 | 871 | 35 | 42 | 4.02% | 4.82% |

| Polybius, 2nd BCE (Gorman/AGDT) | 105693/28271 | 3816/1001 | 648/187 | 803/232 | 16.98%/18.68% | 21.04%/23.18% |

| Diodorus Siculus, 1st BCE (Gorman/AGDT) | 25692/25660 | 991/991 | 245/244 | 308/307 | 24.72%/24.62% | 31.08%/30.98% |

| Dionysius Halicarnassus, 1st BCE (Gorman) | 30312 | 1067 | 135 | 162 | 12.65% | 15.18% |

| Josephus, 1st CE (Gorman) | 24987 | 1039 | 113 | 131 | 10.88% | 12.61% |

| Plutarch, 1st/2nd CE (Gorman/AGDT) | 37203/22124 | 1479/865 | 230/163 | 287/203 | 15.55%/18.84% | 19.41%/23.47 |

| Apollodorus-Ps., 1st/2nd CE (AGDT) | 1265 | 51 | 3 | 3 | 5.88% | 5.88% |

| Appian, 2nd CE (Gorman) | 25665 | 966 | 204 | 248 | 21.12% | 25.67% |

| Athenaeus, 2nd/3rd CE (Gorman/AGDT) | 86219/45585 | 4734/2525 | 340/175 | 376/195 | 7.18%/6.93% | 7.94%/7.72% |

4.3. Genitive absolute in PapyGreek corpus

As seen in Table 1, the percentage of sentences containing the GA construction from all sentences in the corpus is 4.2% for the original layer, and somewhat higher in the regularized layer, as we have more fragmentary or missing branches in the original. The higher percentage in the regularized layer may indicate that the construction is often present in a formulaic phrase that has been easy for the editors to supplement. Nonetheless, with such a small corpus, one should never take these percentages as very precise indicators. However, when we split the corpus down to different text types, one striking tendency can be seen: the corpus consists of mostly letters and petitions, and it is very clear that the petitions contain the majority—roughly 65%—of the GA constructions (see Table 5). [38] Moreover, 80% of petitions contain at least one GA construction. [39] From 278 letters, on the other hand, only 36 contain one or more GA construction. [40] It is, therefore, quite safe to say that the language in petitions—legal and formulaic but also narrative—favors the GA construction, but private letters usually avoid it. One can expect that when the number of contracts rises in the corpus, they have somewhat higher numbers of the GA than the letters—at the moment we see that in texts not yet in the released corpus. [41]

| Text type | Text count | Texts with GA (% of texts within type) | GAs within type (% of GAs within corpus) |

| Letter | 278 | 36 (13%) | 53 (28%) |

| Petition (with attachments) | 59 | 48 (81%) | 123 (65%) |

| Contract | 12 | 1 (8%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Other types | 13 | 6 (46%) | 9 (4.7%) |

| Text type not defined | 4 | 1 (25%) | 3 (1.6%) |

4.4. Comparisons between the literary and PapyGreek corpora

For the purpose of devising queries that encompass all instances of the GA, we created a typology based on the possible dependency relations between the participles and their subjects (agents). Four types of GA were defined (see Figure 6): type 1) single participle governing a single agent; type 2) single participle governing co-ordinated agents; type 3) co-ordinated participles sharing a single agent; type 4) co-ordinated participles governing shared co-ordinated agents.

5. Other Corpora and the Genitive Absolute

5.1. PROIEL

The parallel corpus of the New Testament for several ancient Indo-European languages includes also the Greek New Testament. [48] In addition, the PROIEL project has included parts of Herodotus’ Histories with a larger sample than the AGDT/Gorman corpus and a postclassical work, Sphrantzes’ Chronicles from the 15th century (Table 6). The annotation framework is similar but not identical to the AGDT formalism. [49] The data is available in different formats—e.g., xml and conll) for scholarly use—but it can also be queried directly in the Norwegian CLARIN’s Infrastructure for the Exploration of Syntax and Semantics (INESS). [50]

| PROIEL corpus | tokens | sentences | GA total | GA % (of sentences) |

| Hdt | 85080 | 5446 | 343 | 6.30% |

| NT | 140763 | 11261 | 240 | 2.13% |

| Chron | 24612 | 976 | 140 | 14.34% |

5.2. DUKE-NLP

We decided not to incorporate the Duke-nlp data into the Kiln platform, but rather experiment querying the GA in the Duke-nlp files with DendroSearch because it seemed useful to test the query engine provided by the creators of the data and since some inconsistencies (see below) would have made the data incomparable with the ones we tested with Kiln. [54] The results brought us a large number of possible GA constructions. Since the searches were not done identically with the Kiln queries and since we do not have all the same data for them (such as the sentence counts), and sometimes the automated parsing caused false-positive results, [55] Table 7 should be read with due caution. However, we can say something on the basis of those results: the overall percentage of GA (NB. of tokens, not sentences) is, at 0.28%, lower than what we have in the three corpora seen in point 8 of Table 1, despite the false positives. It is more useful, however, to compare the figures within the corpus itself. The highest percentage—nearly 1%—comes from the file named “administration”; the one called “declarations” is in second; “contracts,” “pronouncements,” and “reports” score more than the letters. This is in line with our earlier observation on the lesser use of the GA in letters. A noteworthy but also expected feature came out when combining a lemma constraint to the search; as mentioned above (note 44), the regnal year dating is expressed with a GA construction. In the query of instances in which the participle is of the lemma βασιλεύω, almost half of the type 2 GA numbers were regnal dating formulae in contracts, but not so much in other document types, and the number was especially low in letters. In the type 1 GA, the lemma had a significantly smaller effect in all document types.

| Duke-nlp corpus (several files joined) |

tokens | GA type 1 (+3?) | GA type 2 [56] | GA% (of tokens) |

| Contracts (1+2+3) | 1030574 | 3156 | 487 | 0.353% |

| Pronouncements | 86993 | 259 | 26.5 | 0.328% |

| Declarations (1+2) | 525445 | 2618 | 162.5 | 0.529% |

| Reports | 284799 | 914 | 61 | 0.342% |

| Administration | 16902 | 164 | 3 | 0.988% |

| Accounts | 37526 | 20 | 1 | 0.056% |

| Labels | 20755 | 3 | 0 | 0.014% |

| Receipts (1+2) | 721445 | 751 | 66.5 | 0.113% |

| Letters (1+2+3) | 841466 | 1840 | 93 | 0.230% |

| Lists (1+2+3+4) | 1310900 | 742 | 22.5 | 0.058% |

| Paraliterary | 14543 | 11 | 0 | 0.076% |

| Other | 235800 | 527 | 57.5 | 0.248% |