Teegarden, David A. 2023. “The Athenian Empire and Resistance to Tyranny.” In “The Athenian Empire Anew: Acting Hegemonically, Reacting Locally in the Athenian Arkhē,” ed. Aaron Hershkowitz and Michael McGlin, special issue, Classics@ 23. https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HLNC.ESSAY:103490527.

Abstract

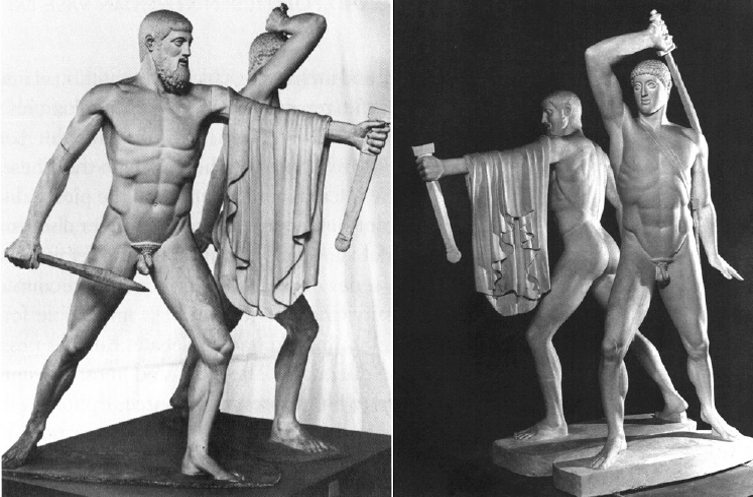

1. The Tyrannicide Staters from Kyzikos

2. Spreading the Fame of Harmodios and Aristogeiton

2.1 Direct intervention in a city

The only evidence in support of the suspicion that the Athenians might have promoted Harmodios and Aristogeiton by means of direct intervention in an allied city is the fact that the well-known Erythrai Decree contains a clause (lines 32–34) that refers to “the tyrants.”

- IG I3 14 (following the facsimile first published by Böckh in CIG I, p. 891) prints these lines as follows: ἐὰν δέ̣ [τ]ις [‐‐‐‐‐‐|‐‐‐‐‐] το[ῖ]ς τυράννοις [‐‐‐‐] ᾿Ερυθραί[ον] καὶ [‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐|‐‐‐‐] τεθνάτο [‐‐‐‐] πα̣ῖδες [h]οι ὲχς [ἐ]κέν[ο ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐. Note that the words “the tyrants” are in the dative case. A quite adventurous restoration of these lines is Syll.3 41: ἐὰν δ[έ] τ̣ις [ἀ]λ̣ô[ι προ|διδ]ὸς τοῖ̣ς τυράννοις τὲμ π̣ό̣λ̣ι̣ν̣ τ̣ὲ̣ν̣ ᾿Ερυτηραίο̣ν καὶ [αὐτ]ὸς [ν|εποινεὶ] τεθνάτο κ̣α̣ὶ̣ παῖδες̣ [ḥ]οι ἐχς ἐκ̣εί̣νο. “If someone is caught betraying the city of the Erythraians to the tyrants, both he and his children shall be put to death with impunity.”

- Georgia E. Malouchou [11] (following a recently discovered facsimile contained in the notebook of Kyriakos S. Pittakys) prints the lines as follows: ἐὰν δέ̣ τ̣ις [.]ΒΟ[‐‐8‐‐]|ΟΣ[..] τὸς τυράννος ΤΕΜΝΑΝ[1–2]ΟΣ ᾿ΕρυθραΙΝ καὶ [αὐτ]ος [‐ca. 6‐]|ΧΑΓΙ τεθνάτο [κ]α̣[ὶ] παῖδες̣ ḥοι ἐχς ἐκ̣ένο̣. Note that according to this facsimile, the words “the tyrants” are in the accusative case. Malouchou suggests (in her apparatus criticus) that ΤΕΜΝΑΝ[1–2] might be restored as τεχ̣νά[ζει] (‘contrives’) and that its object infinitive might have preceded the words “the tyrants.” She does not provide a suggestion for that infinitive. But, if her suggestion is correct, the essence of the sentence would be something like: “if somebody [contrives to X] the tyrants, … both he … shall be put to death and his children.”

Whatever the correct grammatical case of the words “the tyrants,” the Erythrai Decree is not direct evidence for the Athenians promoting (Athenian style) tyrannicide ideology within their arkhē. Most obviously, there is no reference to killing a tyrant in the decree. In addition, all standard articulations of tyrannicide ideology refer to a singular “tyrant” or the abstract “tyranny.” This is the case for the known tyrant-killing laws and decrees: the decree of Demophantos, the tyrant-killing laws from Athens (Eukrates), Eretria, and Ilion, and the Philites decree from Erythrai. [12] This is also true for Athenian oaths and proclamations: the Heliastic oath (Demosthenes 24.149); the traditional proclamation made at the City Dionysia (Aristophanes Birds 1072–1075). [13]

2.2 Promotion at Athenian festivals

2.3 Promotion by vase painters