I. Introduction: The Digital Nestle-Aland

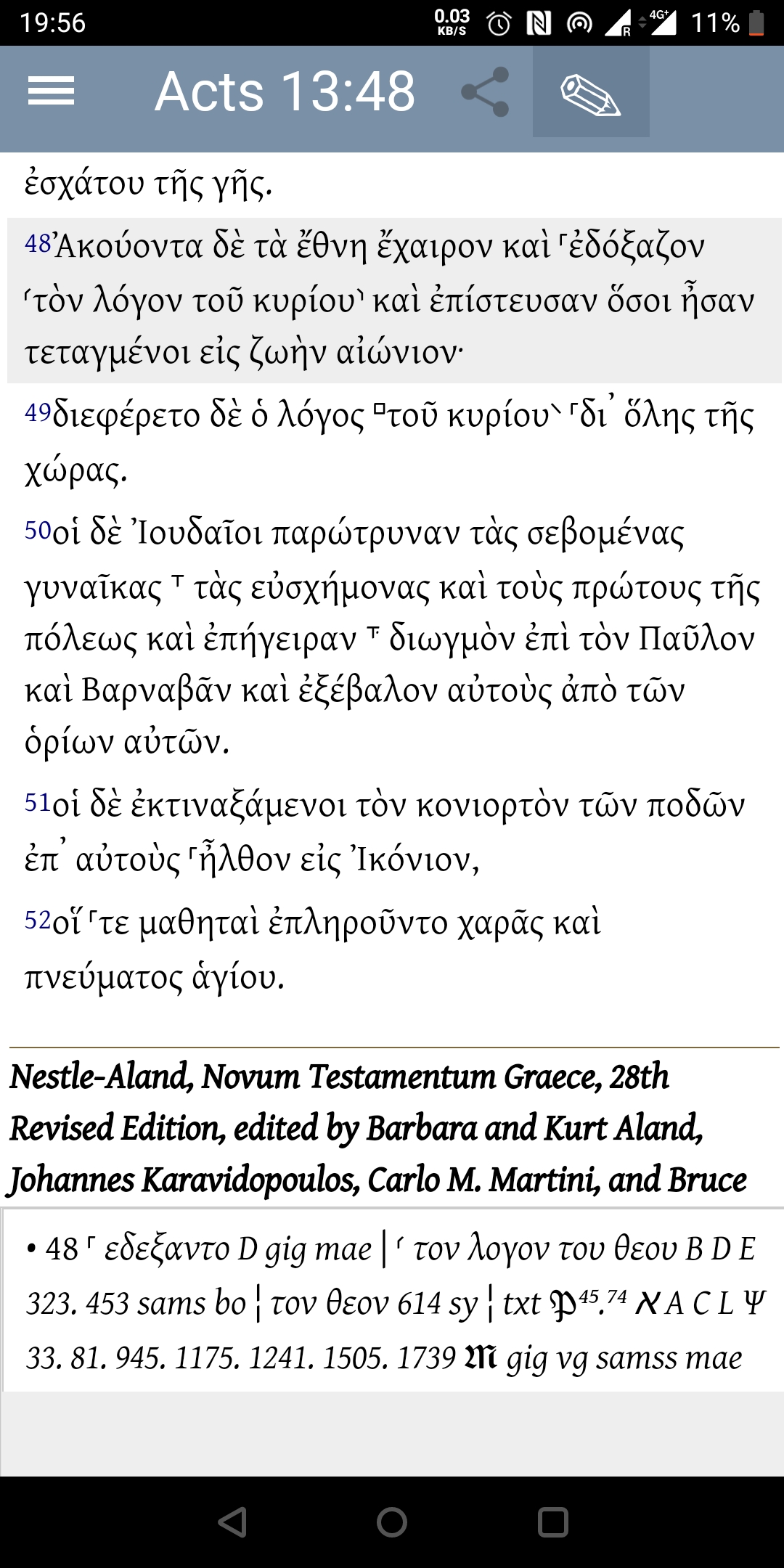

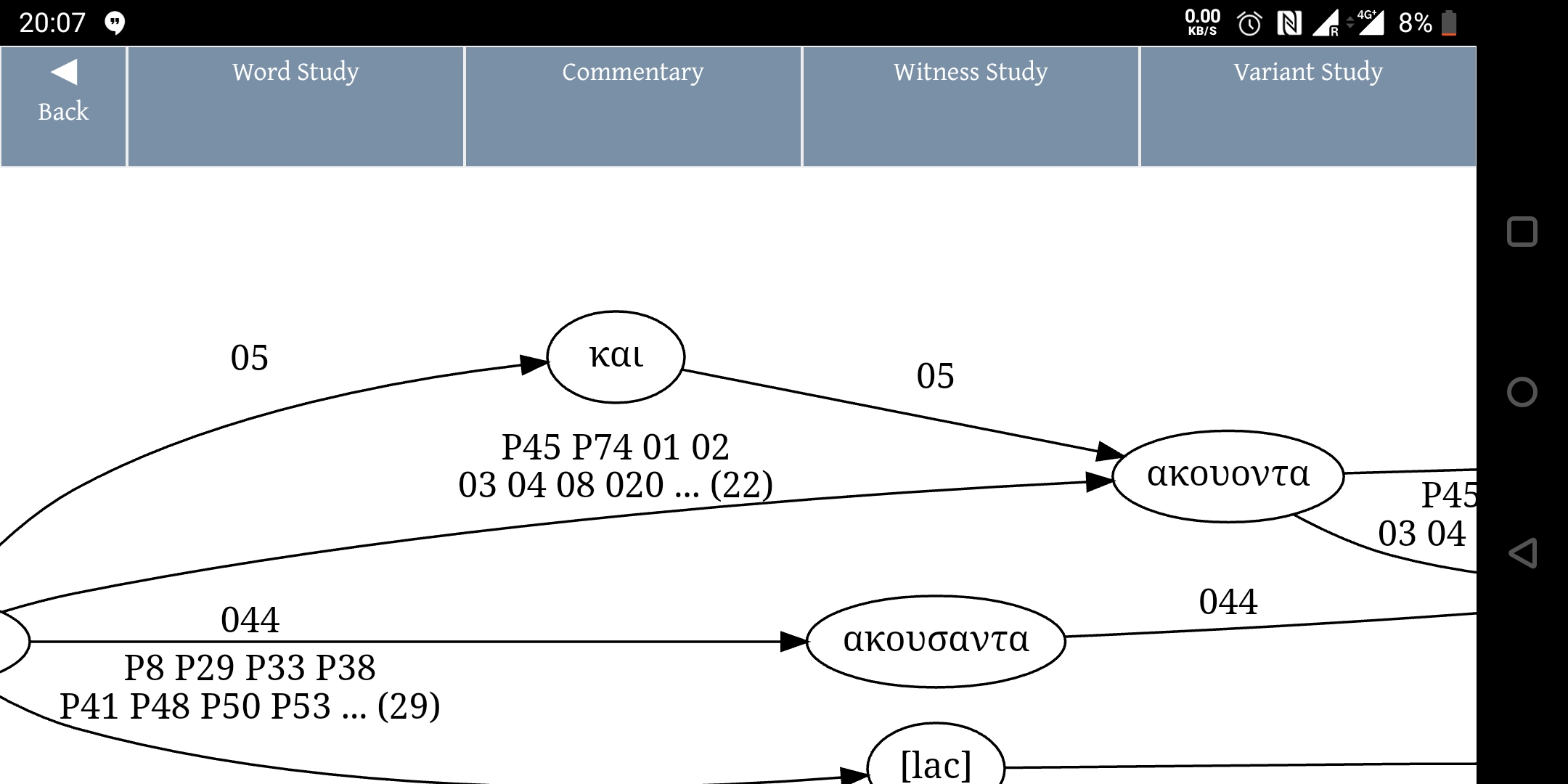

On The SWORD Project you can also pull up graphs that visualize the flow of variants from manuscript to manuscript (Figure 3).

For the time being, these three formats—the PDF, Bible software, and The SWORD Project—are the most direct options to access the NA and its apparatus digitally. But obviously there are other ways to make the NA into more of an interactive digital edition and to equip it with options for personal customization.

The leap forward brought to editing by the digital media is the potential

- to access the evidence live which is hidden behind the sigla in a printed critical apparatus;

- to document the procedures and criteria applied by the editors to construct the apparatus and to reconstruct the initial text;

- to discuss the assessments and decisions of the editors in a forum related to the edition and process them interactively in an individual workspace. [8]

II. Steps to an Open Digital Edition: the dECM

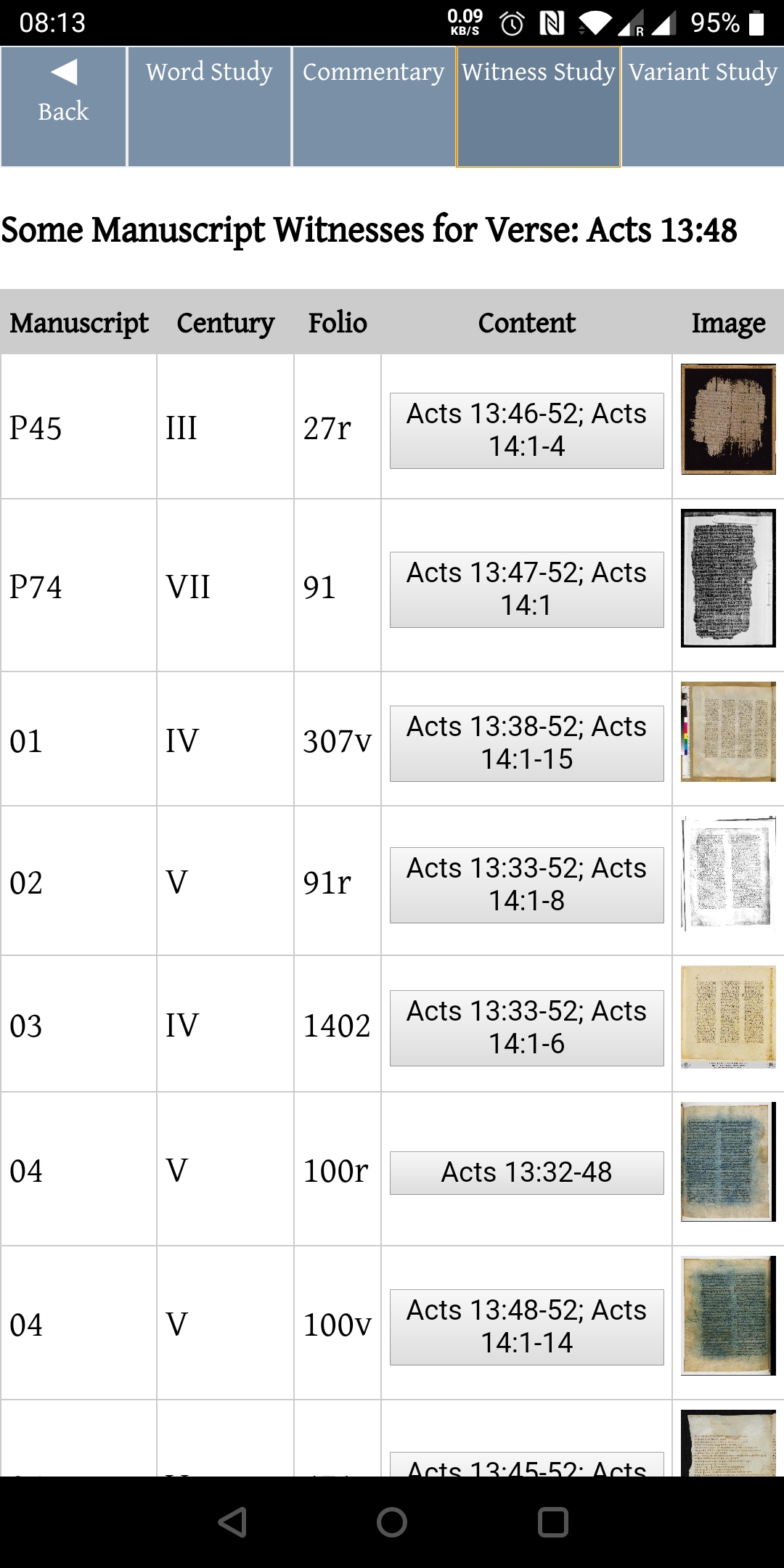

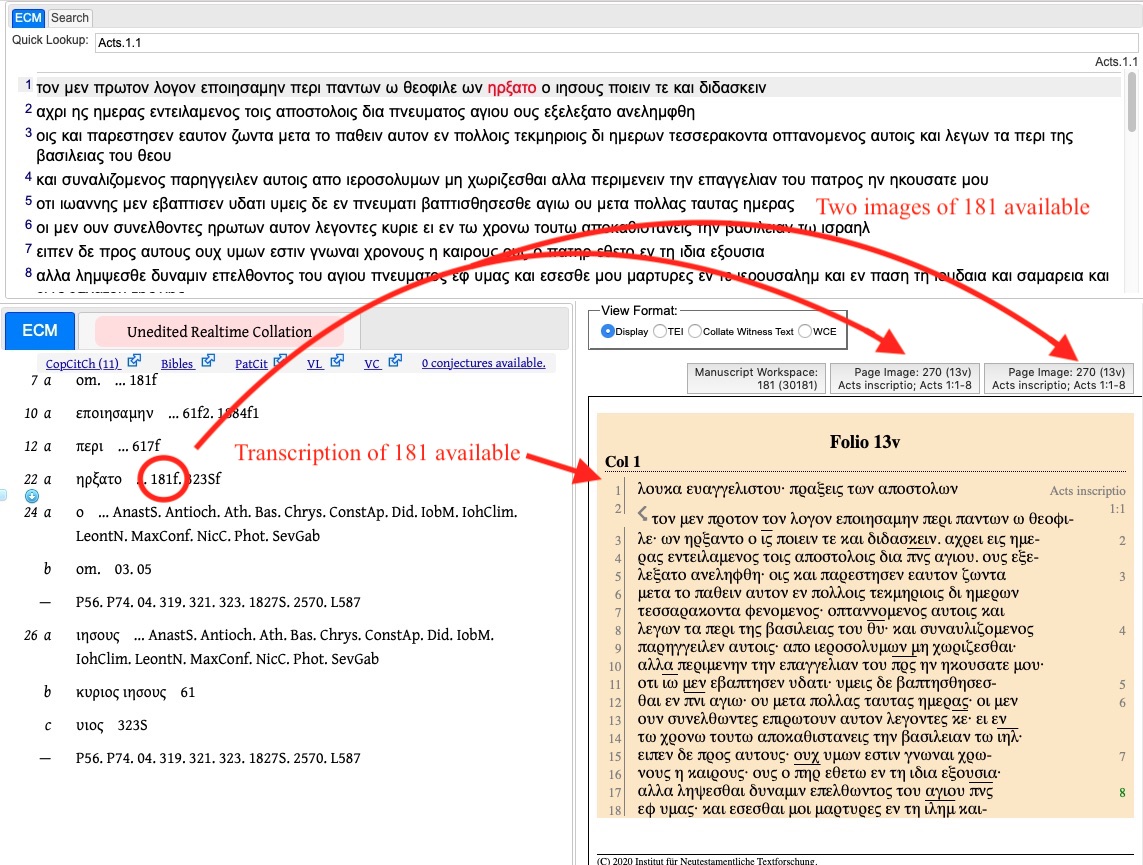

On the NTVMR, the dECM page (https://ntvmr.uni-muenster.de/ecm) defaults to Acts (because so far only Acts is available as a dECM edition). There are a lot of options here. [16] Like The SWORD Project app, clicking on a manuscript, e.g. 181, will bring up its transcription and provide further options for digital images (Figure 4).

This offers a whole new way to explore manuscripts in context rather than having to piece together citations scattered throughout a printed apparatus. [17] The transcriptions in the NTVMR for these manuscripts in Acts are the full transcriptions that were used in the ECM; consequently any mistakes in the apparatus of the ECM will also be found in the NTVMR transcriptions. When a mistake is noticed, it is corrected in the digital transcription here.

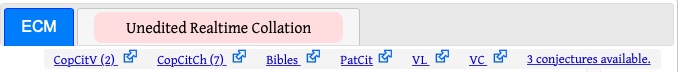

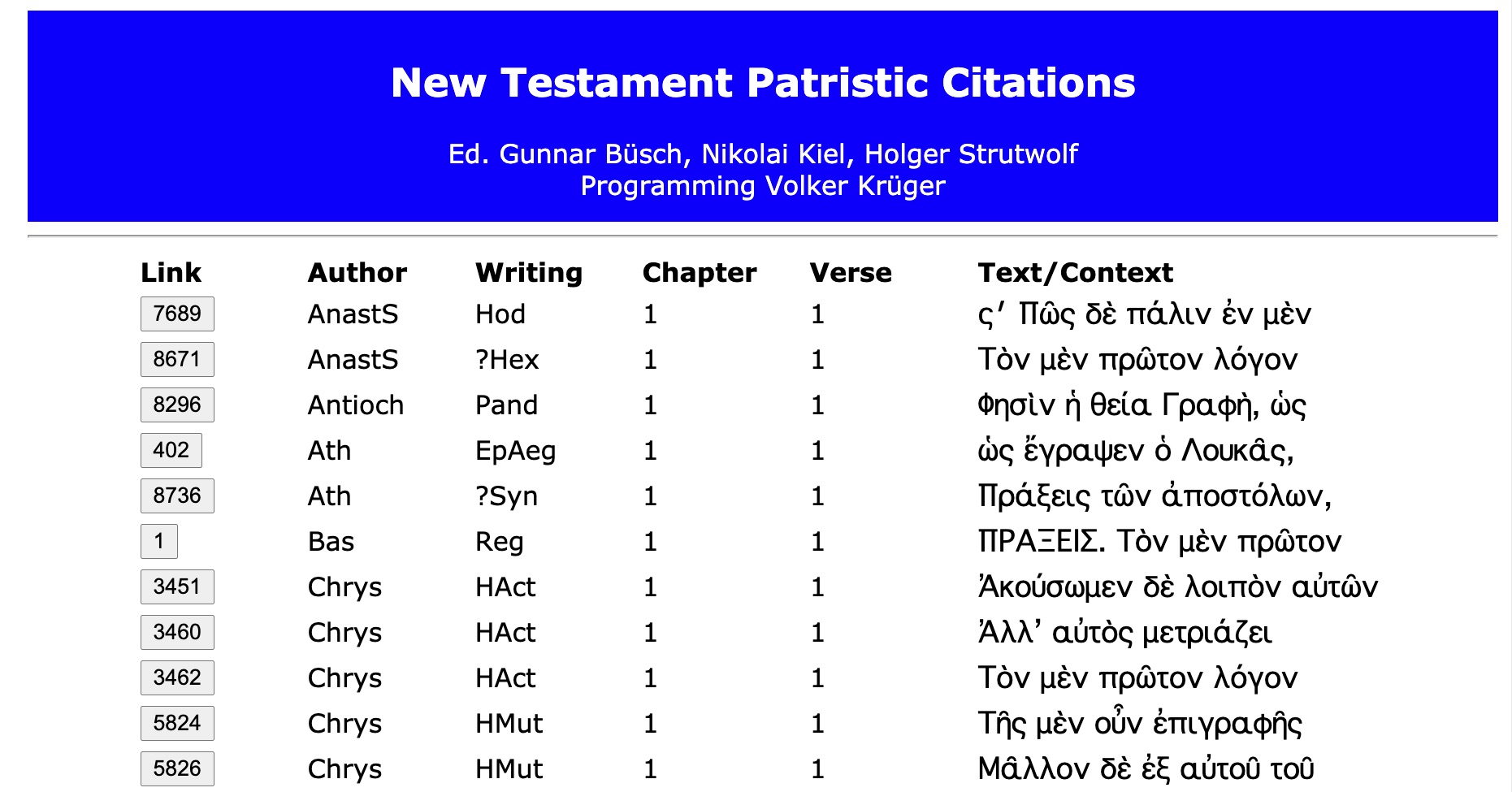

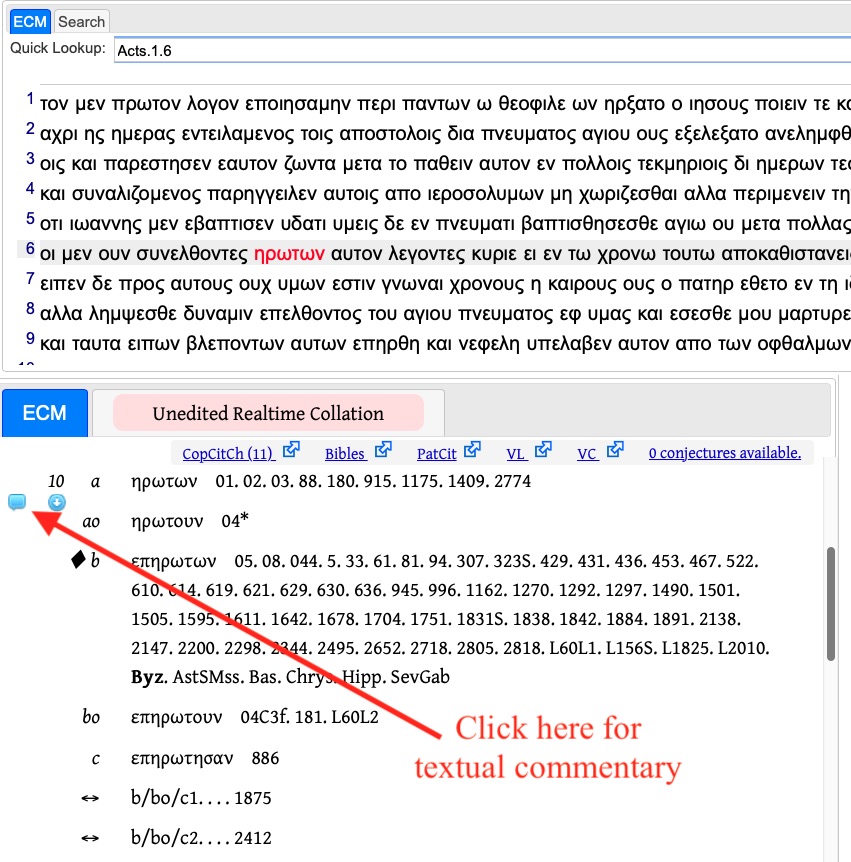

In addition, users have several databases at their fingertips. The ones labeled PatCit, VL, and VC contain the data behind Patristic citations, Latin, and Coptic, respectively, in the ECM (Figure 5). The other databases offer additional tools for research, which is the result of collaboration with other researchers.

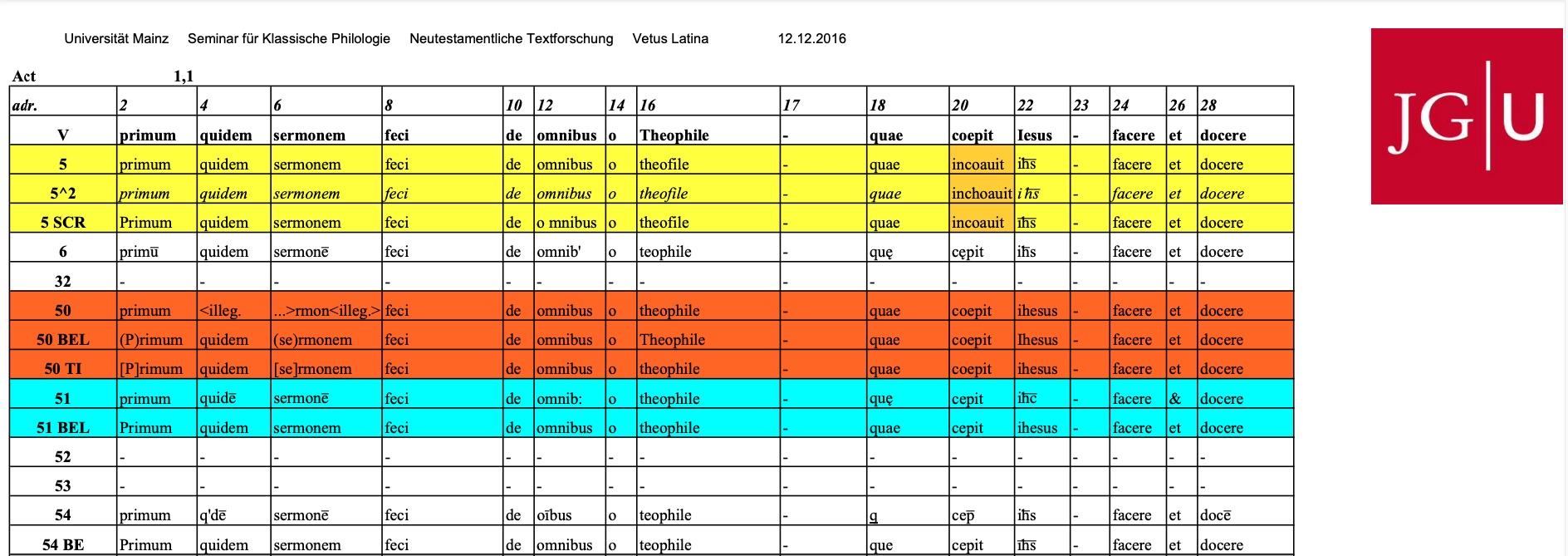

4. The VL link brings users to full transcriptions of Old Latin manuscripts cited in the ECM of Acts (Figure 7). The University of Mainz prepared these transcriptions and kindly allowed them to be used in the ECM of Acts.

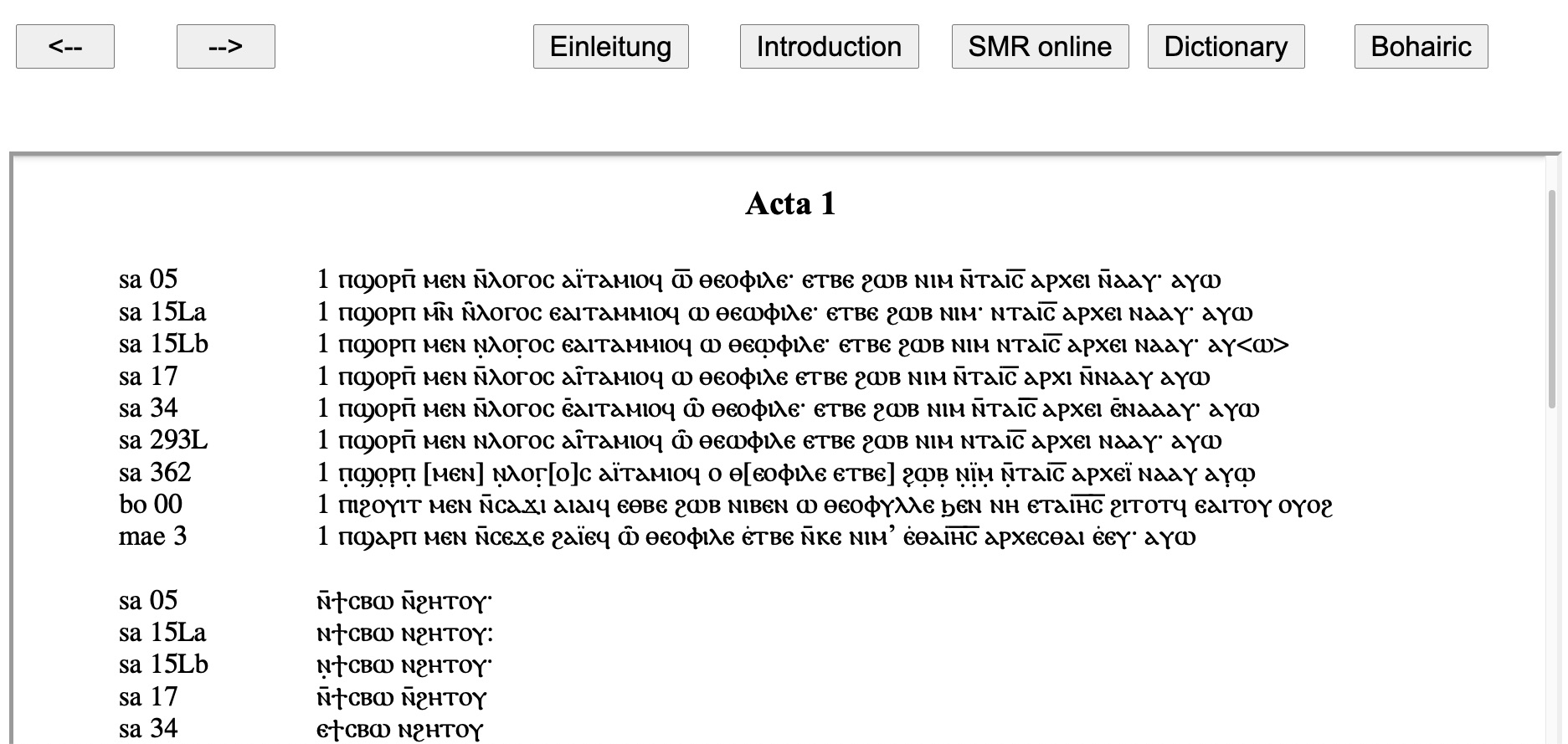

5. The VC link brings the user to full transcriptions of all Coptic witnesses used in the ECM (Figure 8). [20]

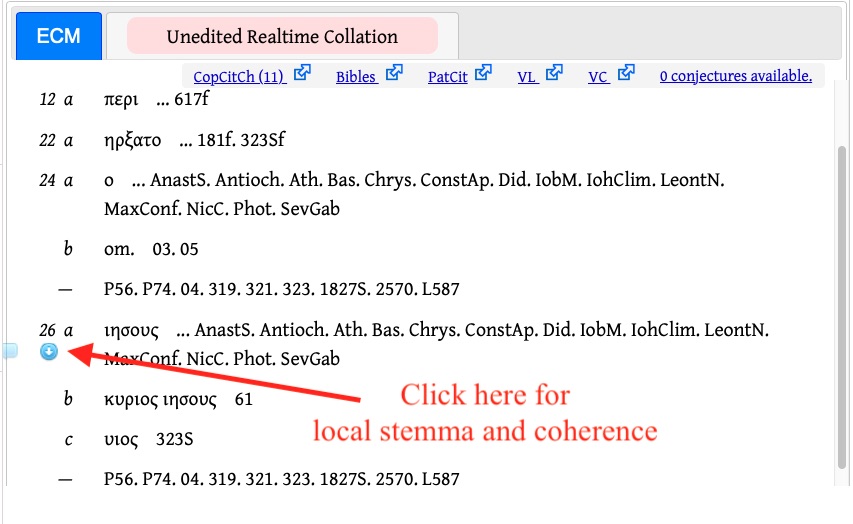

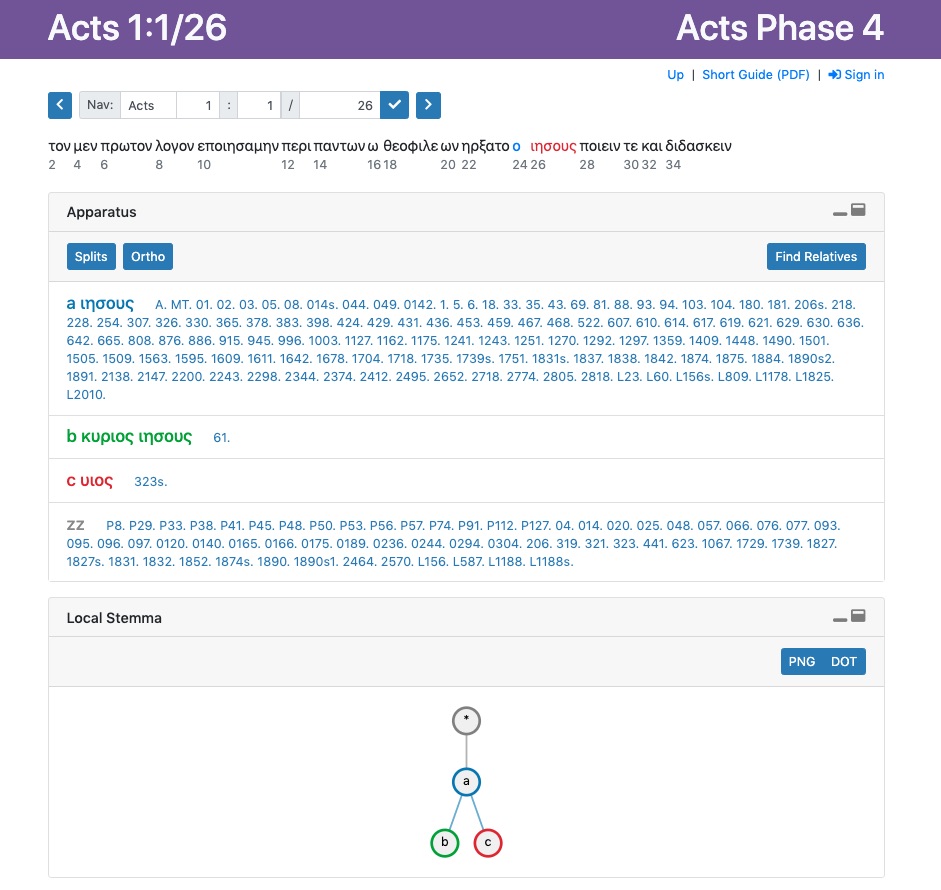

Besides images and transcriptions, the NTVMR also offers access to decisions made by the editorial committee of the ECM. In the dECM, the user can go to any verse in Acts and see the local stemma of texts that the editors have established for a given passage by clicking on the circle with an arrow, [22] which brings the user to the Genealogical Queries portal (Figure 9).

In the field labeled Apparatus, we see there are three variant readings (the manuscripts cited for zz are not included in this passage): (a) ιησους, (b) κυριους, and (c) υιος. In the field labeled Local Stemma, editors’ decisions are visible: variant a is the established text (the Ausgangstext), and variants b and c come from a. (There are more fields to see on this page below but they are related to the editorial method used in the ECM, the CBGM, which is discussed at length in other publications.) [23] Because the editors of the NA have agreed to adopt the results of the ECM, the local stemmata for the ECM can also be applied to the NA. This fulfills the second element on our wishlist for a digital edition, being able to check and assess editorial procedures.

There is also a textual commentary for a selection of Acts passages, e.g. Acts 1:6/10. Clicking on the speech bubble takes the user to the commentary (Figure 11).

The commentary explains why the editors made a textual decision. Users can reply to the textual commentary or pose their own question where there is no existing commentary, which will open up a new discussion (Figure 12).

This forum offers users an opportunity for discussion with the editors of the ECM. Similarly, there is a forum for the NA on the NTVMR (https://ntvmr.uni-muenster.de/na28), and the German Bible Society also fields questions on their site (https://www.die-bibel.de/en/service/contact-us/).

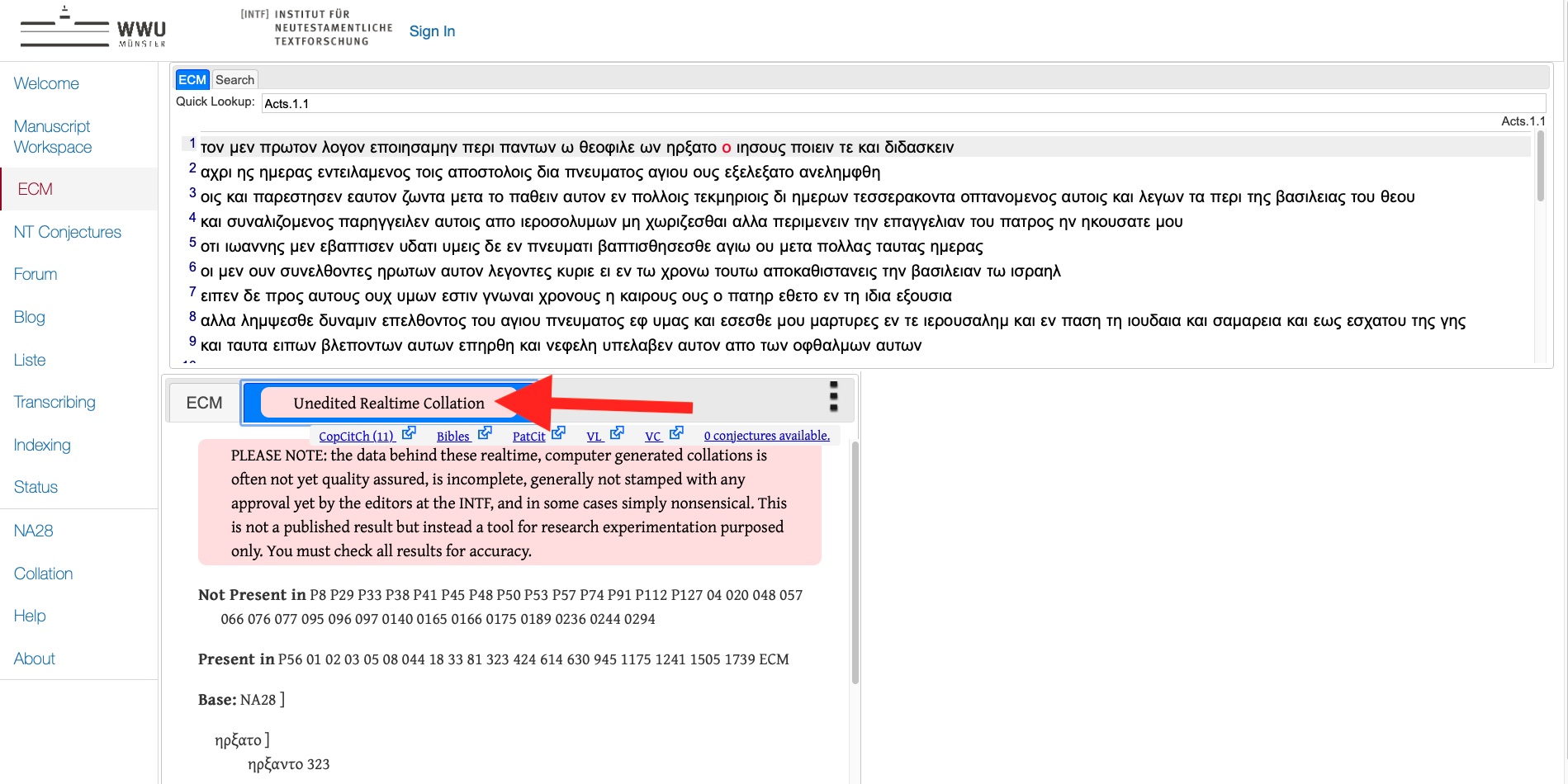

III. Digital Editing on the NTVMR: Unedited Realtime Collation [25]

When using the dECM website, click on the Unedited Realtime Collation tab to begin creating your own edition (Figure 13).

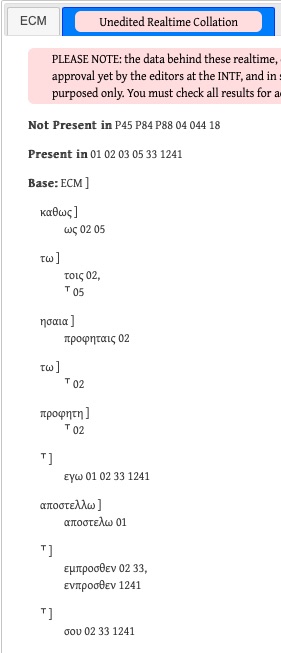

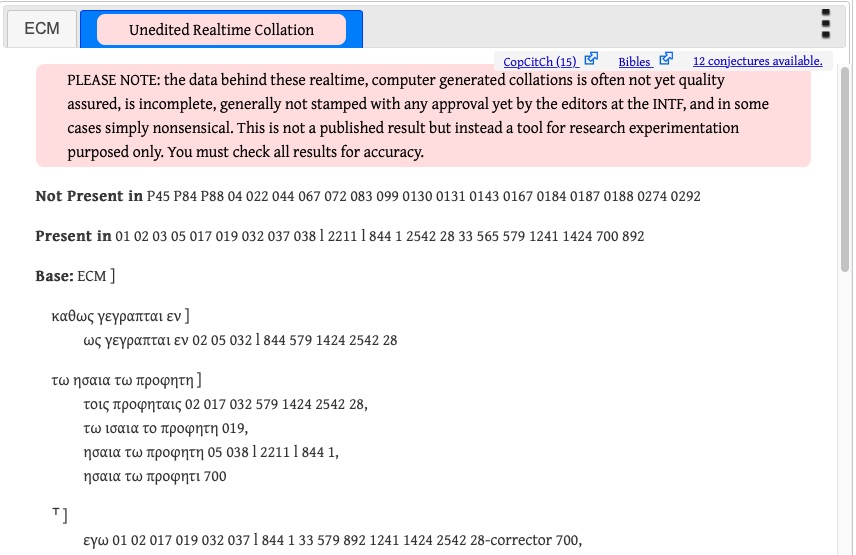

By default you see an automatic collation of all the New Testament papyri (up to P128), many majuscules, and a few minuscules against the NA28 [26] (this base text is labeled as ECM). [27] In the NTVMR, transcriptions are created in an editor developed by the University of Trier. [28] CollateX, a software component that is used to construct critical apparatuses, [29] is a core component used to provide the “realtime” collation. [30] The transcriptions are sent to CollateX and this results in the Unedited Realtime Collation. (ITSEE’s apparatus editor is used primary to produce the edited non-realtime apparatus on the ECM tab.) Because the Unedited Realtime Collation produces an unedited collation, the initial results are not always perfect. See for example the automatic result of Mk 1:2 (Figure 14).

But all of this can be perfected and the program is customizable. The NTVMR lets a user add rules before sending the data to CollateX and re-collate to see the result of those rules. After taking the necessary steps (explained below), the collation can look like the results in Figure 15. [31]

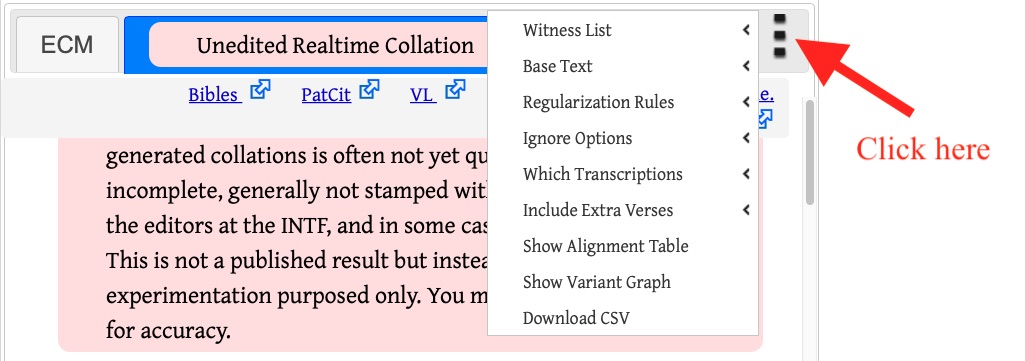

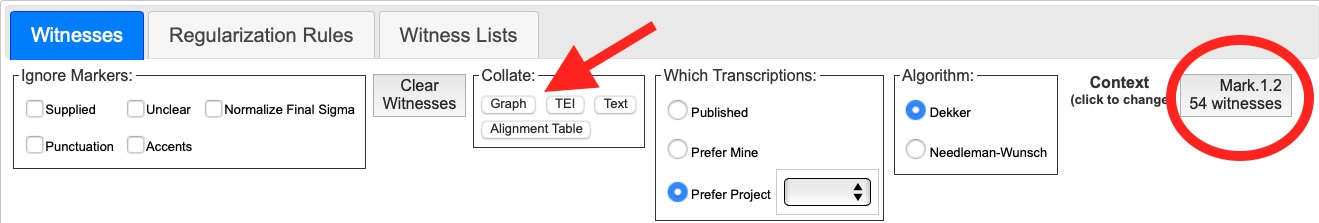

C. Customization: Here are the options for customization (Figure 16).

- 1. Witness list

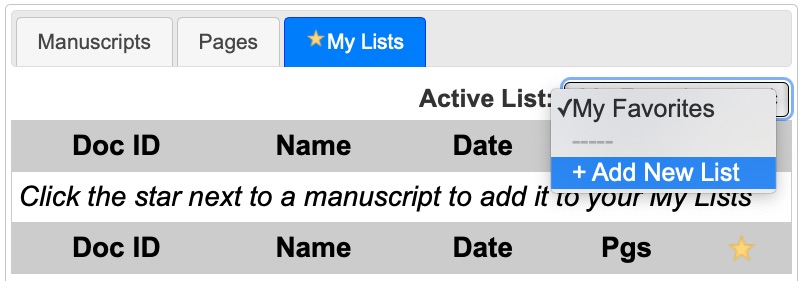

- Create your own witness list in Manuscript Workspace by clicking on Active List and then + Add New List (Figure 17). [32]

- 2. Base text

- You can use anything that has a transcription in the NTVMR for a base text.

- 3. Regularization Rules

- Regularization Rules are any customizations you have made to orthography or other spellings, as well as adjustments to collations (the latter is explained below in Show Alignment Table). After you make your own rules, the setting should be changed to Personal; otherwise your rules will not appear.

- 4. Ignore Options

- You also have the option to include or exclude punctuation, brackets, underdots, and accents in the transcriptions.

- 5. Which Transcriptions

- A benefit of using the NTVMR is the availability of many transcriptions. The option “Always Use Published” will give you what was used for the ECM volumes. Every manuscript used for the ECM of Acts has transcriptions available, as well as some of the well-known manuscripts such as Codex Sinaiticus, Vaticanus, Bezae, and some papyri which have transcriptions available for the whole New Testament (where they are extant). Another advantage of using the NTVMR is that if you disagree with a transcription it is possible to change it yourself and then select “Prefer mine if present.” With this setting, any transcription you have done will be present (as long as you have selected this manuscript in your witness list, see step 1 above). Thus, this can enable you to conduct fresh research based on your own work.

- 6. Include Extra Verses

- Sometimes sense units or variants span more than one verse. With the option to include extra verses, one to four verses can be added to the beginning and end of a given verse for collation.

- 7. Show Alignment Table

- The alignment table is where fine-tuning of the automatic collation takes place. The collation will not automatically resemble the variant units in the NA. As a default, the collations are divided into one-word units. By selecting a beginning and end of a unit in the alignment table, a “parallel segmentation rule” can be set that will now combine these words into one unit (this can be thought of as a variation unit). [34] If you wanted, you can set the words together to resemble the variation units in the NA.

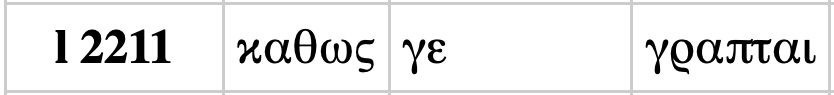

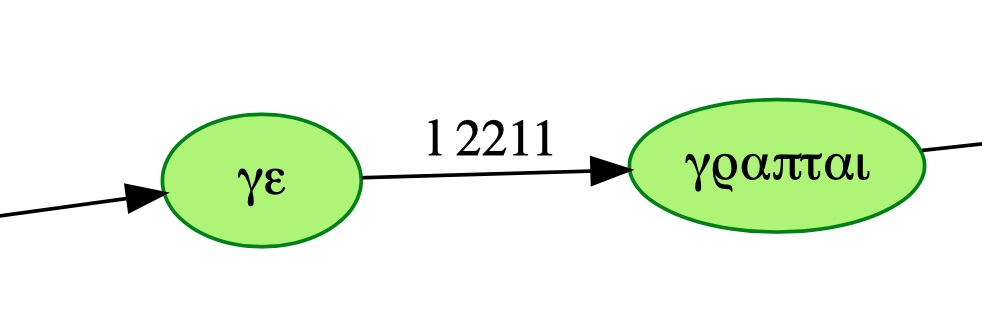

Any misaligned or problematic collations can be fixed here. Take for example the incorrect word split in L2211: γε and γραπται in Mk 1:2 (Figure 18).

This can be fixed on the Collation page, which can be found in the side menu. [35] Once you are in the Collation tool, on the right side of the window select the verse you want to work on. Then click on the Witness Lists tab and scroll down to select your preferred list. Now on the right column, select Use Witness List for Collation.

Go to the Witnesses tab and then on Graph inside of the Collate box (Figure 19). [36]

Click and drag to move the graph or zoom in or out. A close-up of the resulting graph shows the problematic collation (Figure 20):

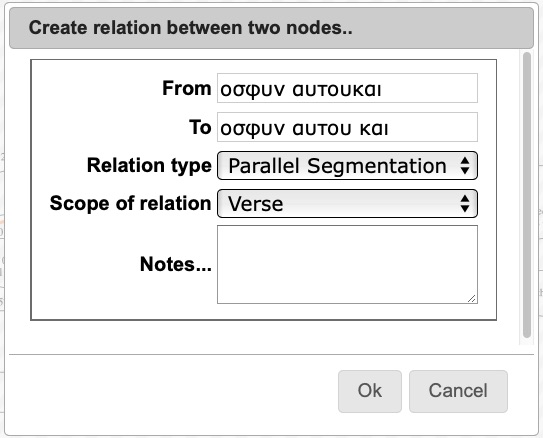

After you click on the pen icon in the top left corner, the graph becomes interactive, meaning you can now click and drag words together to combine them. After dragging two units together, you will be prompted to set the unit how you would like (Figure 21). [37]

Refresh the dECM page in your browser to see the results of your work on the Collate page.

Words that are incorrectly joined together can also be split in the interactive graph. For example, GA 28 in Mark 1:6 reads “αυτουκαι.” Click and drag either the preceding or following word onto αυτουκαι. You will be prompted to input the correct segmentation (Figure 22).

This process can be repeated until you get the desired collation for your project.

- 8. Show Variant Graph

- This was briefly mentioned as it pertains to the Collation page, but in the Unedited Realtime Collation page, the Variant Graph is not editable. It offers a static visual diagram of the flow of segmentation units for each manuscript.

- 9. Download CSV

- Finally, the Alignment Table can be downloaded.

And that is the basics of building and customizing an edition.