1. Papyrological and Palaeographical Resources

1.1 Trismegistos

1.2 Papyri.info

1.3 Catalogues of collections

1.4 Palaeographical catalogues

2. D-scribes project

2.1 Three case-studies

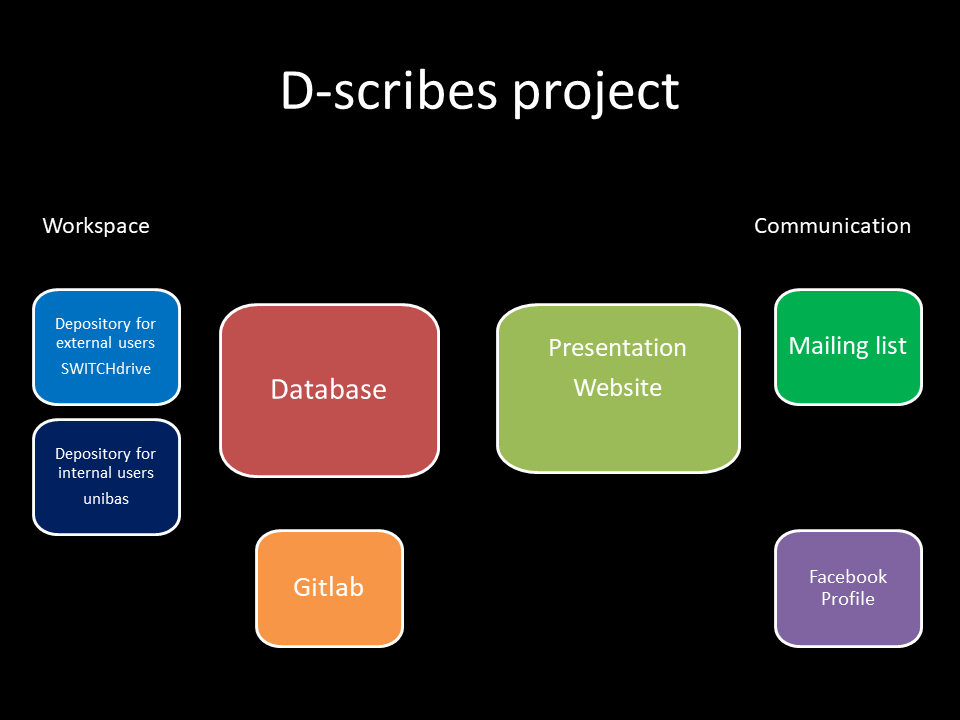

2.2 Infrastructure

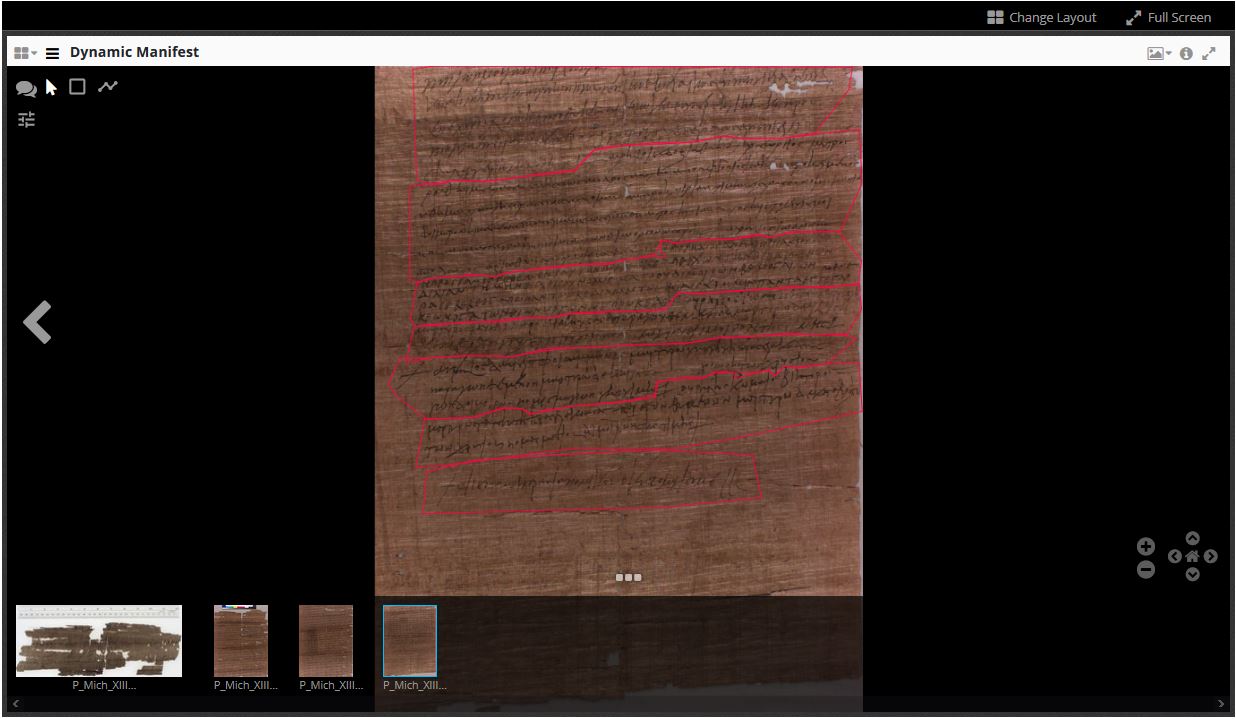

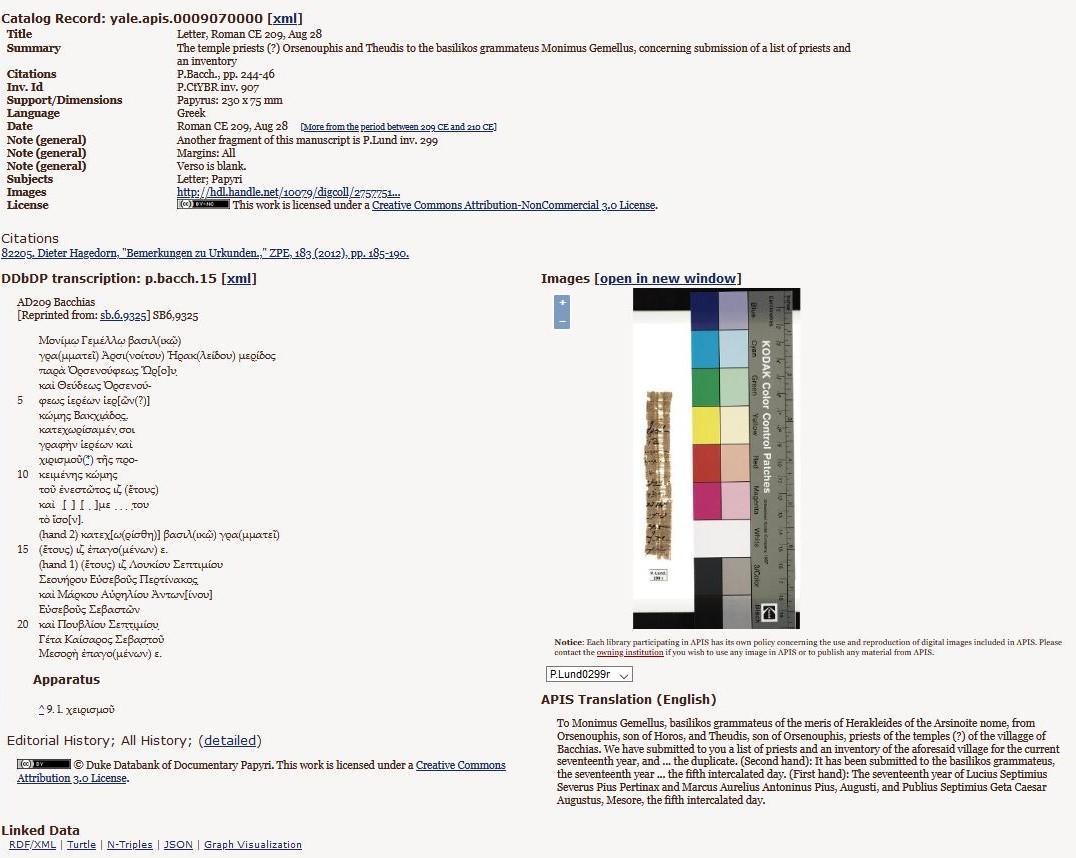

In order to coordinate the teamwork, D-scribes benefits from several resources offered by the University of Basel (Figure 2). Gitlab [24] is used for organizing the tasks, dealing with issues, and documenting processes when the team changes, which is unavoidable since student assistants join the project for a limited period of time. Sharing the data and software prototypes is made possible thanks to two depositories: a folder accessible only for the team members within the University network and a Switchdrive [25] depository to share specific folders with external collaborators. An SQL database has been constructed in the scope of the project. It gathers metadata on each papyrus of the three case-studies, uses the IIIF [26] standard and includes a Mirador [27] viewer to annotate papyrus images. Metadata include links to Papyri.info and Trismegistos (along with TM identifiers for texts and persons) to facilitate future integration.

2.3 Showcase

A showcase is about to be launched that will enable the visualization of all the passages of contracts written by identified notaries in the Dioscorus archive. For each notary, three categories of samples will be displayed: the bodies of the documents that he penned, the signatures (subscriptions) which ascertain his identity, and pieces without signature but assigned to him by specialists based on palaeographical comparison. In a second step, data will be released concerning the other writers encountered in these notarial documents, which are the parties and witnesses (Figure 3). This showcase offers the possibility to catch a first glimpse on the sociology of the act of writing in an Egyptian village by showing samples of handwriting performed by priests, soldiers, and shepherds, among others. A second strand of the showcase will display Iliad papyri illustrating various handwriting styles.