Antonopoulos, Andreas P. 2023. “Little Kottalos and the moon of Akeses: On Herodas’ Didaskalos (Mimiamb 3).” In “Γέρα: Studies in honor of Professor Menelaos Christopoulos,” ed. Athina Papachrysostomou, Andreas P. Antonopoulos, Alexandros-Fotios Mitsis, Fay Papadimitriou, and Panagiota Taktikou, special issue, Classics@ 25. https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HLNC.ESSAY:103900195.

| A. PROVERBIAL COMPARISONS | |||

| Nr. | Saying | Line(s) | Speaker |

| 1. | οἶον Ἀίδην βλέψας when he looks at it as if it were Hades |

17 | Metrotime |

| 2. | λιπαρώτεραι … τῆς ληκύθου much more shiny … than our oil-flask |

19–21 | Metrotime |

| 3. | ὄκως νιν ἐκ τετρημένης ἠθεῖ he lets it trickle out as if from a holed jug |

33 | Metrotime |

| 4. | κάθητ᾽ ὄκως τις καλλίης he sits … like a monkey |

41 | Metrotime |

| 5. | ὤσπερ ἴτ‹ρ›ια θλῆται is broken like wafers |

44 | Metrotime |

| 6. | (κατ᾿ ὔλην) οἶα Δήλιος κυρτεὺς ἐν τῇ θαλάσσῃ (τὠμβλὺ τῆς ζοῆς τρίβων) (dragging out his pointless life in the wood) like a Delian pot-fisherman at sea |

51–52 | Metrotime |

| 7. | τὰς ἐβδόμας δ᾽ ἄμεινον εἰκάδας τ᾽ οἶδε τῶν ἀστροδιφέων he knows the seventh and twentieth of the month better than the starwatchers |

53–54 | Metrotime |

| 8. | ἐγώ σε θήσω κοσμιώτερον κούρης I shall make you better behaved than a girl |

66 | Lampriskos |

| 9. | ἐστὶν ὔδρης ποικιλώτερος he is much more subtle than a water-snake |

89 | Metrotime |

| 10. | ἄμεινον τῆς Κλεοῦς ἀναγνῶναι he will read better than Cleo |

92 | Metrotime |

| B. OTHER PROVERBIAL EXPRESSIONS | |||

| 11. | δεῖρον, ἄχρις ἠ ψυχή αὐτοῦ ἐπὶ χειλέων μοῦνον ἠ κακὴ λειφθῇ flay this boy on his shoulder, until his wretched soul is just left on his lips |

3–4 | Metrotime |

| 12. | κἢν τὰ Ναννάκου κλαύσω even if I weep the tears of Nannacus |

10 | Metrotime |

| 13. | ὤστε μηδ᾽ ὀδόντα κινῆσαι so that we cannot move even a tooth [21] |

49 | Metrotime |

| 14. | τῇ Ἀκέσεω σεληναίῃ δείξοντες to show him to Akeses’ moon |

61–62 | Lampriskos |

| 15. | κινεῦντα μηδὲ κάρφος not moving even a straw |

67 | Lampriskos |

| 16. | πρὶν χολῆ<ι> βῆξαι before my bile makes me cough [22] |

70 | Lampriskos |

| 17. | καὶ περνάς οὐδείς σ᾽ ἐπαινέσειεν no one, even if selling you, would praise you |

75 | Lampriskos |

| 18. | οὐδ᾽ ὄκου χώρης οἰ μῦς ὀμοίως τὸν σίδηρον τρώγουσιν not even where mice eat iron equally |

75–76 | Lampriskos |

| 19. | ὄσσην δὲ καὶ τὴν γλάσσαν… ἔσχηκας what a tongue you’ve acquired! |

84 | Lampriskos |

| 20. | τὴν γλάσσαν ἐς μέλι πλύνας may you find your tongue washed in honey! [23] |

93 | Lampriskos |

Table 1. Proverbial expressions in Mimiamb 3.

Sharing the same collective cultural experience with Herodas, his audience would have been familiar with these traditional sayings. But this is not the same with the modern reader, who would find several of them strange and even difficult to comprehend. Perhaps the most challenging of all is case 14, which, I believe, provides important information in favour of and about the staging of this mimiamb. The broader passage reads (59–62):

… Εὐθίης κοῦ μοι,

κοῦ Κόκκαλος, κοῦ Φίλλος; οὐ ταχέως τοῦτον

ἀρεῖτ᾽ ἐπ᾽ ὤμου τῇ Ἀκέσεω σεληναίῃ

δείξοντες;LAMPRISKOS:

… Euthias, where are you,

and Kokkalos, and Phillos? Quickly lift him

on your shoulders to show him to Akeses’ moon.

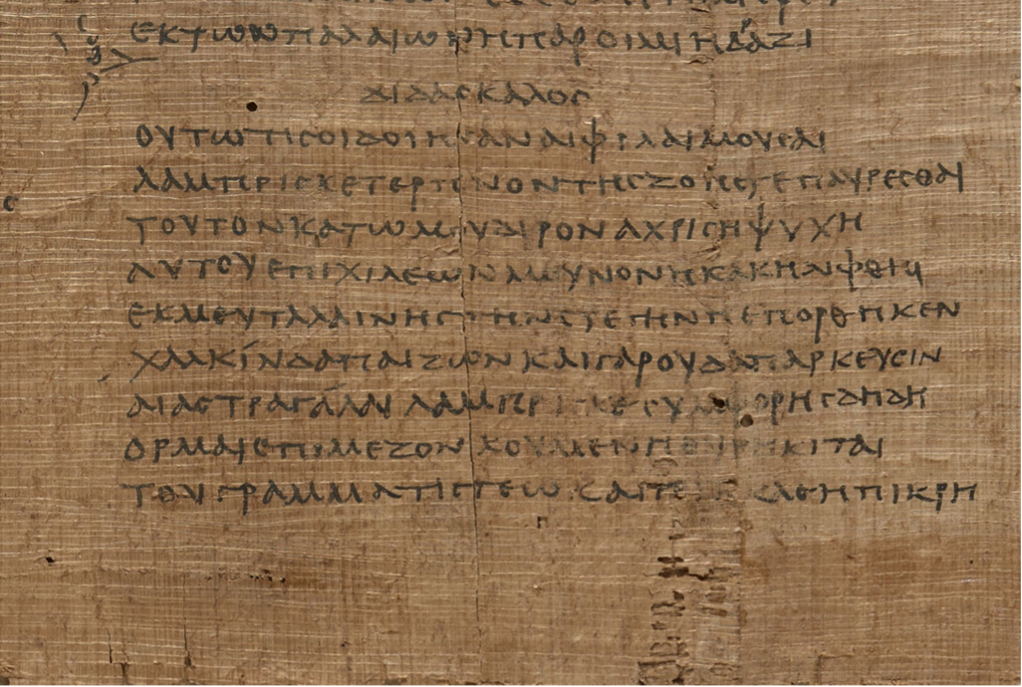

Lampriskos is referring here to a type of punishment common in antiquity; we have visual evidence for it with regard to school-discipline in particular. [24] Our first piece of visual evidence is a fresco from the “House of Julia Felix” in Pompeii, dated to the first century AD (Figure 2). The victim is lifted up on the shoulders of a standing schoolmate, while his legs are supported by another one who is kneeling. His back and buttocks are exposed and presented for punishment to the schoolmaster (most likely), who is holding a whip in his right arm and is ready to strike.

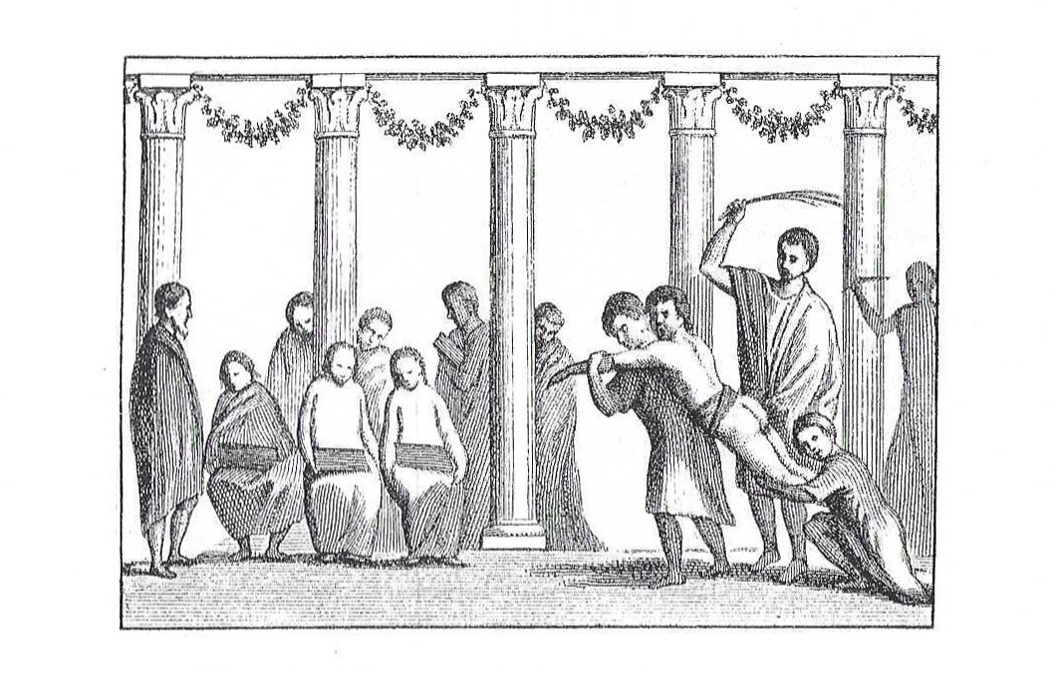

The second visual parallel is from a gemstone of the Graeco-Roman period, Berlin, Staatliche Museen FG 6918 (formerly Stosch collection) (Figure 3). This time the victim is held up in the air in a horizontal position by two fellow students who are standing. The second one, who is holding the victim’s legs with his left arm, is also responsible for the whipping; he is equipped with a whip in his right arm.

A similar punishment is mentioned in Apuleius Metamorphoses 9.28. In this case an angry old baker is having a teenage boy flogged for committing adultery with his wife:

Still, the reference “showing him to Akeses’ moon” is puzzling. First of all, δείξοντες with σεληναίῃ [28] (“showing him to the moon”) is metaphorical and must refer to the body position of Kottalos, with his back and buttocks looking towards the sky. The similarity with Figures 2 and 3 is immediately apparent. The expression itself is illustrated with the help of Macho fr. 10. 110–111: [29]

πιὼν …… having shown the kylix to the sun

he drunk (the wine) quickly…

It is obvious that τῷ θ’ ἡλίῳ … δείξας means that the drinker turned his kylix bottoms-up. The reference to the “moon” in our case rather than the “sun” was prompted by the mention of Akeses. [30] The “moon of Akeses” was a proverbial expression and our passage is in effect our only ancient example of it being used in context [31] —no wonder it has caused difficulty to modern interpreters. Elsewhere it is found in the form of a lemma in paroemiographers. There are two main versions:

a) Diogenianus 1.57, who was reproduced by Apostolius 1.90:

b) Pausanias Att. τ 26, who was reproduced by Photius τ 585, Suda τ 512, and Apostolius 16.44):

a) It was based on Headlam’s misunderstanding of the paroemiographers. Confused by the juxtaposition of Akeses’ moon to indefinite pledges for the Laconian moon in Diogenianus 6.30 (see n. 32), he argued that:

But this is not what our sources say about Akeses. He became proverbial for his laziness and tardiness, not for the certain fulfilment of his promises and his sense of responsibility. The emphasis cannot be on him, but should rather be on the moon.

c) There is no plausible explanation as to why Lampriskos should ever have delayed punishing Kottalos. He is so brutal, methodic and impatient with regard to punishments that one feels he could hardly have resisted beating Kottalos at the first opportunity, as becomes apparent from lines 68–69:

ᾦ τοὺς πεδήτας κἀποτάκτους λωβεῦμαι;

with which I mutilate those whom I’ve fettered and the ones I’ve set apart? [39]

It is amazing that Lampriskos even maintains different groups of pupils for punishment, apparently in accordance with the gravity of misconduct: πεδῆτες and ἀπότακτοι are not really what one would expect to find at a school, even an ancient one! Such a sadist character would show no mercy to someone like Kottalos.

And, most important, d) Kottalos has indeed experienced the variety and violence of Lampriskos’ punishing instruments; in lines 71–73 he is begging him to choose for him “not the piercing one, but the other (whip)”:

καὶ τοῦ γενείου τῆς τε Κόττιδος ψυχῆς,

μὴ τῷ με δριμεῖ, τῷ ’τέρῳ δὲ λώβησαι.

There are two interesting parallels from Old Comedy. The first contains a hyperbole with regard to the prolongation of punishment and comes from Aristophanes Equites 69–70:

… εἰ δὲ μή, πατούμενοι

ὑπὸ τοῦ γέροντος ὀκταπλάσιον χέζομεν.

… if we don’t (i.e. pay bribes to Paphlagon), the master

will pound on us till we shit out eight times as much. [40]

In the latter, Aristophanes Acharnenses 80–84, the full-moon features as a marker of an excessively long time period:

ΠΡΕΣΒΕΥΤΗΣ:

ἔτει τετάρτῳ δ᾿ εἰς τὰ βασίλει᾿ ἤλθομεν·

ἀλλ᾿ εἰς ἀπόπατον ᾤχετο στρατιὰν λαβών,

κἄχεζεν ὀκτὼ μῆνας ἐπὶ χρυσῶν ὀρῶν.

ΔΙΚΑΙΟΠΟΛΙΣ:

πόσου δὲ τὸν πρωκτὸν χρόνου ξυνήγαγεν;

τῇ πανσελήνῳ;

AMBASSADOR:

So, after three years we got to the royal palace,

but the King had gone off with an army to a latrine,

and he stayed shitting for eight months upon the Golden Hills.

DIKAIOPOLIS:

And when was it he closed up his arsehole?

At the full-moon? [41]