Mitrea, Mihail. 2025. “Performing Holy Foolery in Late Byzantium: Philotheos Kokkinos’s Life of St. Sabas the Younger.” In “Performance and Performativity in Late Antiquity and Byzantium,” ed. Niki Tsironi, special issue, Classics@ 24. https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HLNC.ESSAY:104135606.

Introduction

A late Byzantine holy fool

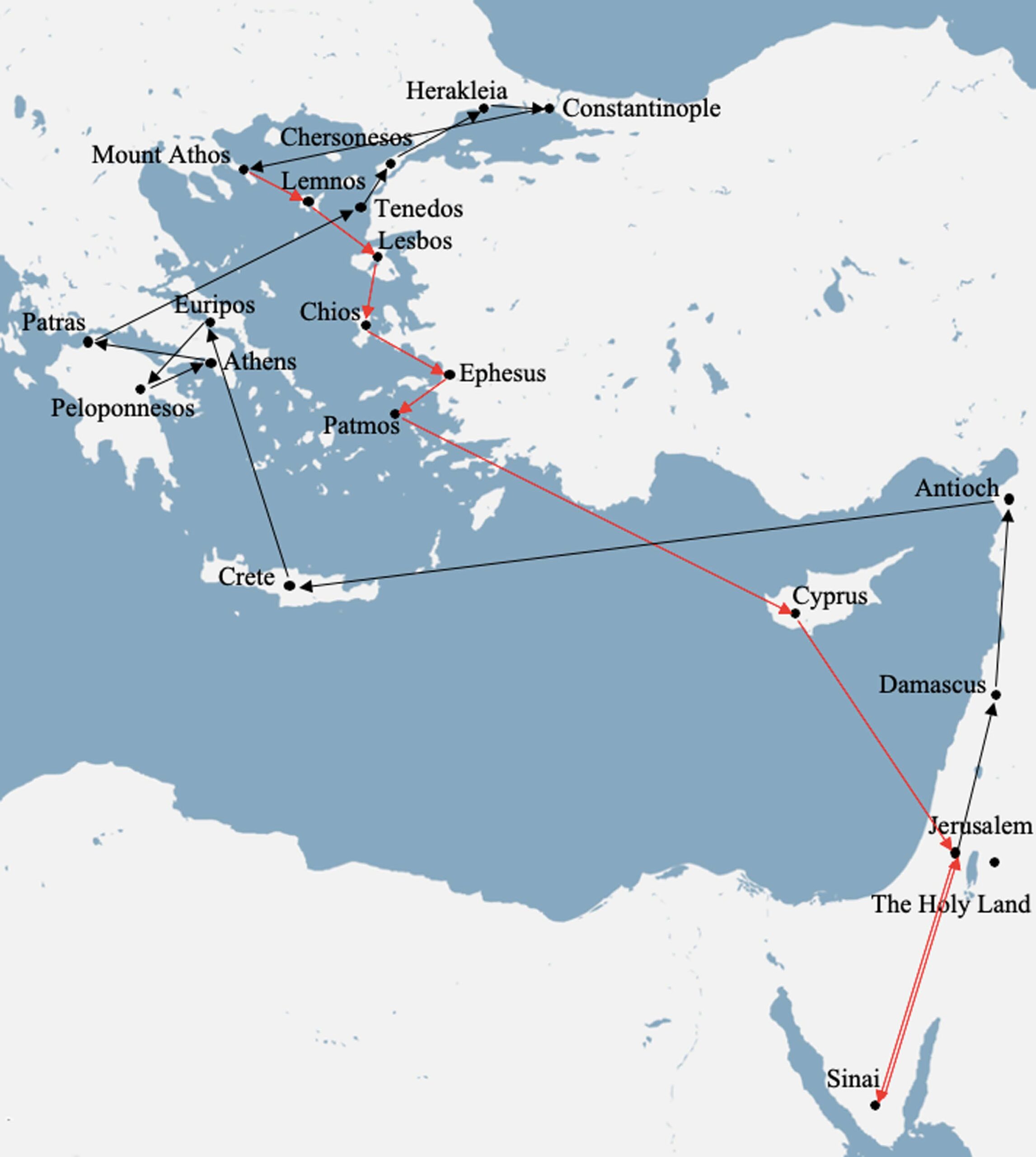

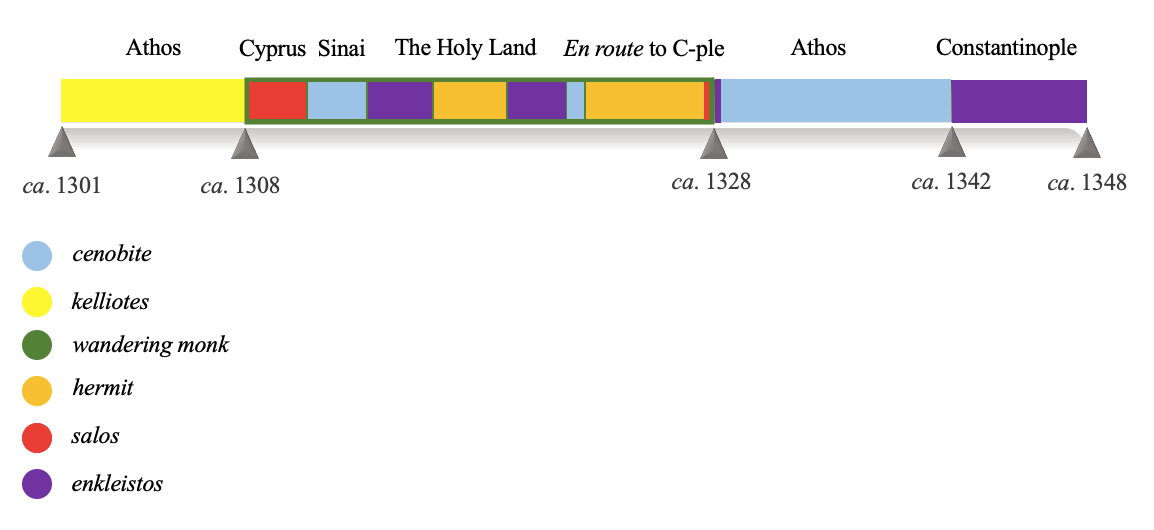

Situating Sabas’s holy foolery within his monastic trajectory serves to better highlight his aims and performance of môria. He reaches Cyprus as a young man in his mid-twenties, after spending around seven years on Athos as a kelliôtês under the spiritual guidance of an elderly monk. Cyprus is his first major stop in a twenty-year long itinerary that takes him as far as the Holy Land and Sinai. Unlike Symeon of Emesa, who assumed the mask of folly when he was already un homme d’âge mûr, at the end of a long career as a hermit, Sabas embraces holy foolery at the beginning of the eremitic stage of his monastic trajectory. However, he only commits to this monastic way of life temporarily. After leaving Cyprus, he pursues many, if not all, other forms of monastic life: he is a cenobite at Saint Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai, a wandering monk throughout the Holy Land, a recluse in several caves (in the Holy Land and Thracian Herakleia) and monasteries (Mar Saba, Saint Diomedes, and Chora in Constantinople), and a hermit. Kokkinos includes an extensive narrative section in which his hero makes explicit his desire to follow every path to perfection, including holy foolery, as dangerous as it may be:

More importantly, as I have argued elsewhere, Kokkinos’s overarching aim in composing a Life for his spiritual father is to present him as the paragon of the hesychastic way of life and turn his vita into a hagiographical argument in support of hesychasm. [21] Consequently, an underlying stream of hesychastic way of life runs through all stages of Sabas’s monastic life, including his holy foolery.

Performing holy foolery

As expected, Sabas’s first act of holy foolery occurs in a public space and entails a physical transformation. While wandering through an urban settlement, we are told by Kokkinos that a local woman admires the beauty of Sabas’s body, which was white, untouched by the harshness of the elements and unmarred by the intensity of his ascetic struggles: “For he was at the beginning of his present [ascetic] struggle, and he had not yet become dark, as expected, by the immediate assaults of the air, nor by the solar and wintry strokes.” [25] To alienate her carnal desires and criticize more generally the worldly concern with outward appearance and “the smoothness of lust,” [26] Sabas performs his first act of pretended folly. Thus, in an ascetic feat of self-humiliation and a symbolic act intended to project his new identity as a fool, he throws himself into a pit of foul-smelling filth. In the evening, he emerges covered in mud and foul odor, his new costume, as it were, in support of his performance, [27] thereby neutralizing his body as a source of lustful temptation. Kokkinos describes Sabas’s public spectacle in detail, activating the imagination and (olfactory) senses of his (extra-diegetic) audience/readers:

Sabas’s altered appearance becomes a vector for the transformation of the woman and lead to her metanoia. Kokkinos writes that she sheds tears and is healed from her previous lack of self-control. This makes the holy man’s performance successful, since his public, in particular the woman, internalizes the message he intended to convey and is edified:

In the first encounter, which takes place again in an urban setting, in the middle of an unnamed Cypriot city, Sabas crosses paths with a Latin nobleman, who makes an intimidating display of power through his pomp and retinue of personal guards. [33] The nobleman takes notice of Sabas’s scant and peculiar clothing and suspects him of being a spy who uses his rags as a deceptive disguise—a detail which hints to the political undertones of this narrative section of the vita. He therefore orders his guards to seize the holy man and asks him to introduce himself. Bound by his vow of silence, Sabas does not comply with this request. Moreover, he uses a reed to knock off the nobleman’s hat to the ground. Kokkinos explains that Sabas’s gesture of provocation is meant to convey to the arrogant Latin nobleman the message that worldly fame is transient and by no means superior to ashes and dust:

According to the hagiographer, this message is unsurprisingly lost to the Latin nobleman, who perceives the gesture as an insult and consequently orders his guards to beat Sabas. Kokkinos vividly (and somewhat exaggeratedly) depicts the savage beating the holy man receives, which causes pieces of his flesh to fly from his body, crushes his bones, and reddens the ground with the streams of his blood—a hematic and spectacular scene that could easily contend with (and even inspire) those in Hollywood movies:

This scene starkly contrasts the Latin nobleman’s position of power to Sabas’s vulnerability. Kokkinos is careful to underline for his (extra-diegetic) audience the difference between the outward and inner station of the two characters. Although on the lowest rung of the social ladder, Sabas has a hidden noble character, while the Latin nobleman is presented as irrational, angry, and out of his mind (i.e. a madman), despite enjoying a high social status. [36]

Even though the holy man fails to convey his intended message to the nobleman, who cannot grasp past the surface meaning of the gesture, his performance successfully fuses the intra-diegetic audience, who come to his rescue and unanimously condemn the actions of the Latin. The violent spectacle of Sabas’s beating elicits a reaction from the part of the public and draws a number of Orthodox Cypriots, who come together to rescue him from the hands of his aggressors:

Thus, the sight of Sabas’s beatings causes the members of the indigenous Orthodox Cypriots to be fused together, “everyone coming from another side,” as Kokkinos stresses, and act concertedly to save one of their own.