1. Background: What is Textometry? How could it concern Classical Studies?

1.1 What is textometry?

1.2 What is TXM?

1.3 Three (Functions) in One (Digital Edition): Reading, Searching, Analyzing

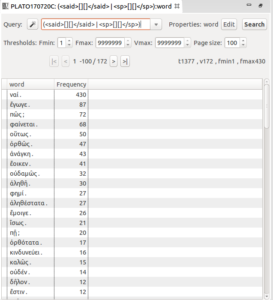

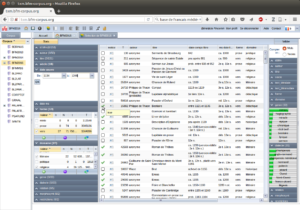

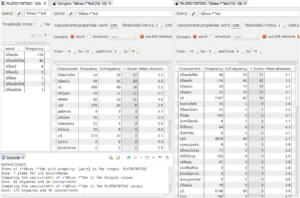

At the same time TXM is a database that manages text documents. Numerous metadata can be associated to each document (such as author, date of composition, text type, etc.), and selection of documents can be built based on the metadata’s values. This can be illustrated by the text selection function in the Base de français médiéval instance of TXM web portal version (Figure 1), [7] which shows very detailed selection panels that are used like database query forms. Furthermore, any textual unit, from words or text chunks to text groups, can be described with metadata information, and then be used to target a selection in combination with any information on any text level. For instance, one may focus on sentences which include some linguistic pattern and which were written within a given time span.

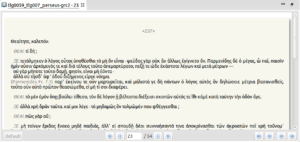

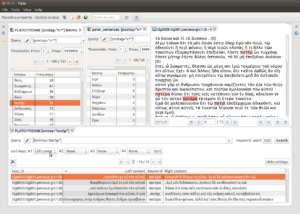

Then, TXM provides a wide range of corpus linguistic functions to process these lexical and textual selections (word frequency lists, KWIC concordance, collocations, keyword analysis, distributions, multidimensional analysis, etc.; see section 1.2). These analytic features can be coupled with a fine text encoding (like XML-TEI), making it possible to record precise philologic information [8] and to build fine-tuned HTML editions to visualize the text (Figure 2). One important feature of the process is the possibility to manage and distinguish information used as text content (words to be searched and counted), and information useful to follow the history of the text, assess its structure, and assist text reading and interpretation (critical apparatus, editorial text divisions, speech turn labels, etc.). If available, facsimiles of source documents can be displayed so that the researcher still has a view on the primary document. Thus one keeps access to information that might have been lost because of necessary digital encoding choices.

2. Corpus Example: Plato’s Work, from Perseus to TXM [9]

2.1 Choice of the texts

2.2 From Perseus TEI encoding to TXM

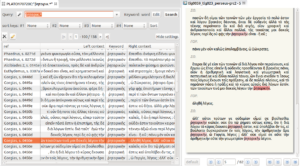

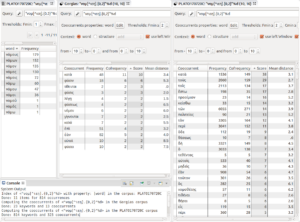

Another XSL stylesheet builds the default references provided for word matches in KWIC concordance view: we chose to show the usual name for the text followed by the Estienne page number (Figure 3). Additionally, we ensured that CTS-URN information, providing unique and standard identifiers to cite digital textual data, is also available at the word level, and can alternatively be chosen for references if needed (Figure 4). The main stylesheet was also used to add page break <pb> elements (with the page number) so as to have the same pages in TXM as in the Perseus edition.

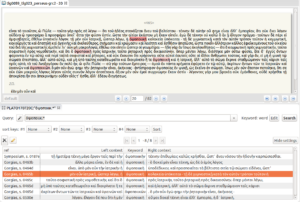

We wanted to keep and show clearly speech turn information and speaker information, without indexing the protagonist’s name as a word to be counted and searched as such. To this aim we declared <speaker> and <label> elements as “Out-of-text-to-edit” element in import parameters. As text encoding in Perseus was heterogeneous, speaker information is also heterogeneous in TXM. Speech turns are defined by either <sp> or <said> element (depending on the text), and speaker is indicated with @who attribute only in <said> elements (but not all of them) for analysis purposes, and is displayed using <label> or <speaker> element content when available (Figure 5).

3. A Typology of Textometric Analyses

3.1 Checking for occurrences and evaluating frequencies

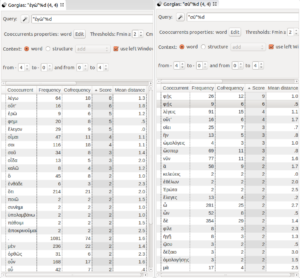

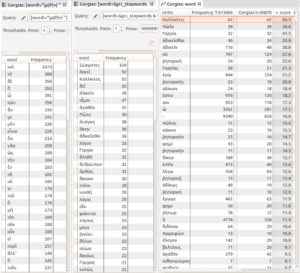

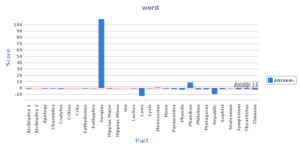

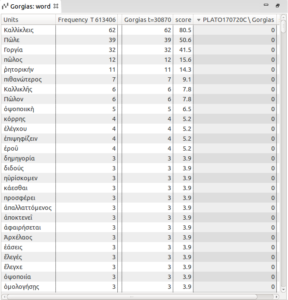

Thus, for Gorgias ‘ vocabulary, we can sort the results either by absolute frequency, or by specificities’ score. In Figure 6, the left panel shows the most frequent words used in Gorgias , which here is useless since the most frequent words of Gorgias are the most frequent words in the corpus of Greek literature: they are “stop-words” like καί, δέ, and so on… [20] If we apply a stop-word filter, [21] we get the most frequent content words of the text, giving account for the main vocabulary used in Gorgias (see middle panel).

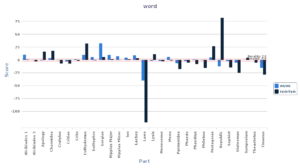

More significant is the fact that they are vocative forms, which are highly frequent in the dialog form: Gorgias is a dialog that is a real exchange (like Laches , Euthydemus , Euthyphro , Hippias Major , for instance), and not the very particular form of platonic dialog where the protagonists do not really interact intensively with each other, which are closer to a series of monologues (like the Laws , the Parmenides , Republic , and the Timaeus ). This “dialogic” aspect of Gorgias became evident at the first sight of the specificities of the dialog: not only the over-use of vocative Σώκρατες, but also such dialog markers as σύ, ἐγώ, ὦ… Those first results show by linguistic means the refutative nature of the Gorgias , which is an attempt to refute sophistic positions and to expose the immoral implications in the hedonist position defended by Callicles. For Socrates, this requires repeatedly questioning the interlocutor (using the vocative), summarizing his argument (by using σὺ + verbs of saying φής, ὡμολόγεις, ἔλεγες, λέγεις…: “you says, you agree, you said…”), and opposing it with his own position (ἐγὼ λέγω, ἔλεγον…) (see also Figure 16 in section 3.4). Admittedly, Gorgias is not the only dialog where we can find those markers; they are common to what the scholarship calls the “Socratic dialogs,” which entails an ἔλεγχος, a refutation. But regarding those features, the textometric approach shows that Gorgias is representative, if not the dialogue par excellence (Figure 7). It reveals that this dialog is paradigmatic, even something of an achievement of this method, since the dialog suddenly ends with a monolog and the acknowledgment that it is impossible to refute those who do not agree with the basic requirements of a rational discussion; that is why it ends with a myth. This analysis confirms the hypothesis that Gorgias is a transitional dialog, where Plato shows the limits of the Socratic method and the necessity to endorse another philosophical method. [23]

3.2 Visualizing the evolution of words or linguistic features

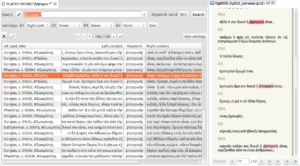

After the dialogic markers, the list of the specificities above shows also what are roughly the main themes of the dialog. The subtitle (which is probably not from the hand of Plato) of Gorgias is “on the rhetoric” (περὶ ῥητορικῆς), and it is well known that the main topic is a critique of the practices of the ῥήτορες, the men who deliver rhetorical speeches and teach rhetoric. Despite this very fact, the word ῥητορική (more precisely, all the forms of the adjective ῥητορικός) [24] appear mostly in the first quarter of the dialog (there are 107 instances in Gorgias , and 85 appear from 448d to 466a, that is, in the discussion with Gorgias himself) (Figure 8).

A glance at the table of frequencies and graph of specificities of the adjective ῥητορικός (all its cognates) in every text of our corpus (Figure 9) shows, however, that ῥητορικός is typical of the Gorgias , for the very reason that it is not very common in Plato’s work: hence, even if Plato does not continually use the word in the dialog, it is nonetheless characteristic of the Gorgias (107 instances, specificity of +108), and to a lesser extent the Phaedrus (21 instances, specificity of +8) (these texts are the only two where the specificity score is greater than +3). [27]

3.3 Refining a word’s meaning with systematic contextual use

Furthermore, the table layout of the KWIC view, coupled with the possibility to sort right and left contexts, reveals the lexical patterns involving the searched word. For instance, sorting on the ‘right context’ of ῥητορική allows one to find the passages where the concept is defined: all the contexts where ῥητορική is followed by the verb εἶμι (to be) or καλέω (to call) (Figure 11).

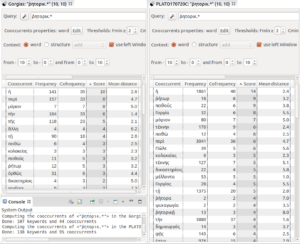

Lastly, to have an overview of the platonic approach of the word ῥητορική, one can have a look at its cooccurrents [31] in the Gorgias : this query shows the words especially used by Plato in proximity with ῥητορική and its cognates (Figure 12). The cooccurrence association score is computed with the same statistic measure as the specificity explained above (the cooccurrence score is precisely the specificity of the cooccurrent word in the part formed by the whole set of contexts of ῥητορική in comparison with its global frequency in the corpus). The common feature of the platonic definition of rhetoric appears within a range from -10 to +10 words: [32] rhetoric is the name of the competence of the ῥήτωρ; Socrates defines it as “producer of persuasion” (e.g. 453a: πειθοῦς δημιουργός, 453d: πειθὼ ποιεῖν); its definition is given through an analogy as part (μόριον) of the art of flattery (κολακεία; e.g. 463b); it is used in the context of the court (δικαστηρίοις)… It is worth noting that those cooccurrents are also the main cooccurents of the word ῥητορική in all Plato’s works.

In the same fashion, the query of the cooccurrents of ἀδικε.* (which matches both ἀδικεῖσθαι and ἀδικεῖν) (Figure 13) instantly points to the passages where Plato makes the comparison between suffering and doing wrong. It is no surprise that the cooccurrents are ἀδικεῖσθαι (because it is most of the time compared to ἀδικεῖν), ἀδικεῖν (for the same reason), τὸ (because the comparison is between the fact of doing or suffering wrong), αἴσχιον, and κακίον (because in the dialog with Polos, the question is mainly whether it is fouler or more evil to commit or to suffer wrongdoing).

An interesting case arises when cooccurrences in the Gorgias happen to be quite different from the cooccurrences in the whole corpus, that is, instances in which a word gets a distinct meaning in the Gorgias . This is the case for νόμος (Figure 14): in the Gorgias ὁ νόμος is mainly used in the discussion with Callicles in the context of the opposition between what is κατὰ νόμον (“according to convention”) and κατὰ φύσιν (“according to nature”). In the other dialogs (and mainly in the Laws ) the cooccurences of νόμος emphasize the description of what will be the law, or conform to the law (ἔστω κατὰ νόμον), or the political action of the law (κείσθω νόμος).

3.4 Computing corpus-based paradigmatic series

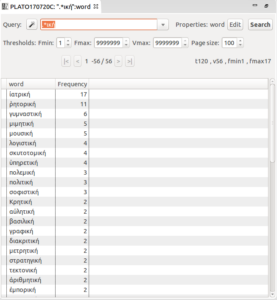

Schiappa emphasized “Plato was a prolific coiner of words ending with -ική denoting ‘art of’” (Schiappa 1990:464). We can have a look at our data to get the set of these kinds of words (Figure 15).

In section 3.1 above, we noted that in the Gorgias , Socrates frequently uses the pronoun σύ with verbs of saying, and ἐγώ with verbs expressing his own position. We can get a rough but systematic summary of verbs more frequently used with ἐγώ and σύ in the Gorgias by computing their cooccurrences in a narrow context window (5 words right and left) (Figure 16).

Another kind of paradigmatic set can be computed on the basis of textual structures. For instance, we can have a look at every one-word answer in the corpus, and thus explore the different ways in Plato’s dialogs to express agreement or disagreement (Figure 17).

Our first example deals with morphosyntactic annotation. The Euthyphro corpus was built from the TreeBank AGDT2 and has morphosyntactic tags, so we can list the verbs occurring in the same sentences as πατήρ (Figure 18).

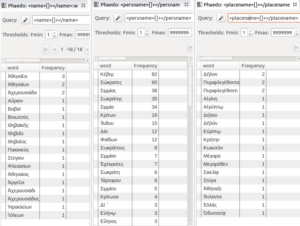

Obviously, all encoded information can be used to define what will be returned. Our second example uses semantic information. In our Plato corpus, one text (the Phaedo ) has been tagged for named entities; we can use this annotation to see precisely which places or people are mentioned in Phaedo (Figure 19).

3.5 Local contrastive analysis of a corpus: Identifying what is typical in a part

As a complement to statistical processing, another way to look at the particularities of the Gorgias ’ vocabulary is by simply listing the words that appear only in Gorgias [33] (Figure 20).

Another word form occurring only in Gorgias is ὀψοποιική (scil. τέχνη, the art of cookery), which is not a common word in ancient Greek. If we consider all the forms of this word, [34] Plato uses it once in the Symposium (187e), when the physicist Eryximachus pronounces that his craft “set high importance on a right use of the appetite for the dainties of the table, that we may cull the pleasure without the disease.” But in Gorgias the word occurs 7 times, mainly in the well-known passages where he makes a comparison between rhetoric and the art of cookery, precisely to show that neither are arts, but kinds of flattery (Figure 21).

3.6 Overall contrastive analysis of a corpus: Identifying the main dimensions structuring a corpus

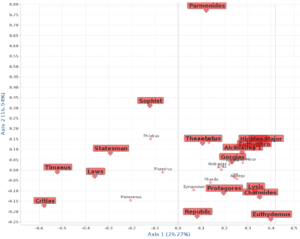

We have generated such an analysis on the Plato corpus. We focused on the 200 most frequent words, which are mainly grammatical words. Each text is represented by the frequencies of its use of these words, which makes a kind of grammatical or stylistic profile (few lexical words). As explained in section 5.2, the x-axis and y-axis represent complex quantitative “mixtures” of words, and they are used to select the best 2D-perspective in the geometric representation of the data. The map (Figure 22) illustrates the relative positions of texts among one another, the main structural associations and oppositions they draw.