What have our tools done for us?

Text-Centric Tools

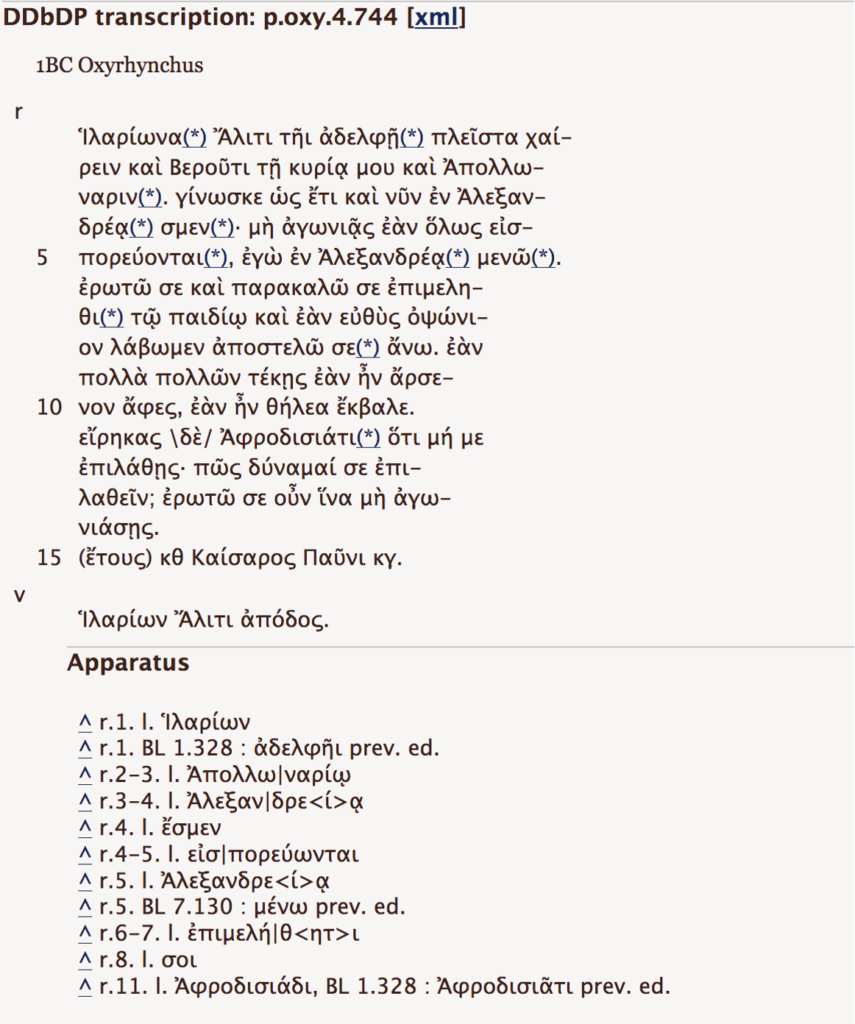

I will start with the text-centric tools. The most important papyrological text resource is the Duke Databank of Documentary Papyri (DDbDP), which began in the 1980s and currently contains over 65,000 transcriptions of mainly Greek but also Latin, Coptic, and a few Arabic texts. [5] It is the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae (TLG) of published papyrological documents, and by “documents” I mean everyday texts, such as petitions, contracts, receipts, private letters, etc., anything but literary and so-called subliterary texts. [6] The DDbDP is a relatively unfiltered corpus with much to offer not only the traditional papyrologist interested in Greco-Roman history (be it political, military, legal, religious, social, etc.), but also Greek philologists and linguists who care about the development of the language outside literary sources preserved in medieval manuscripts. Considered in Unsworth’s terms, the Duke Databank enables more than anything the functions of discovery and comparison, quite often discovery through comparison. Any given search across the databank has the potential to unite the trajectories of two acts: the original entry of the data and the quest of the researcher. The result may be the discovery of information not previously known to the user, but known to others, or the acquisition of new information. Acquisition of new information can take the form of the discovery of new evidence (a hitherto unrecognized fragment of a Roman will, for example), or the establishment of parallels and associations that enable the unraveling of a previously unsolved textual problem, or even the physical joining of two pieces of the same text (not infrequently a philological act confirmed by visual comparison of photos) (Figure 1).

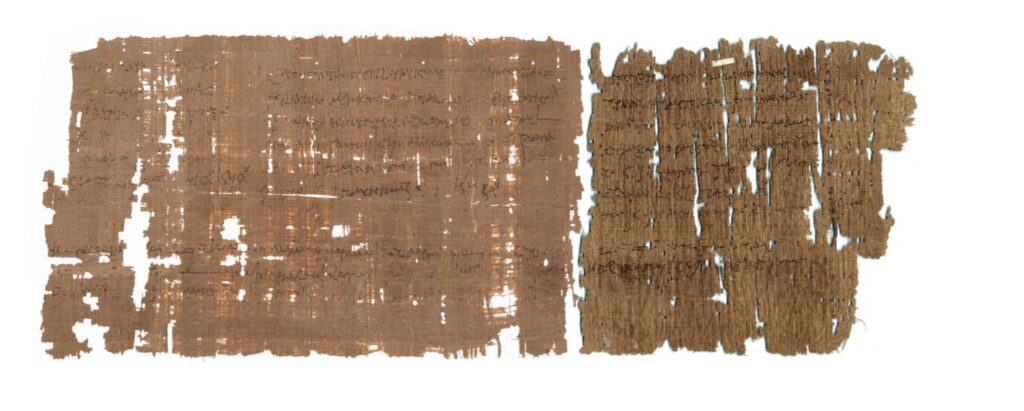

The importance of the refining benefit of the Databank cannot be overstated, and I wish to linger on it for a moment. The renowned papyrologist Herbert Youtie wrote in 1963 that the papyrologist “knows that if he could guarantee the perfection of his transcriptions, he could hope to be forgiven even the total omission of all the rest,” meaning the commentary, general summary, etc. [7] What is implicit in Youtie’s statement is the fact that in a majority of cases, the papyrologist, no matter how good he or she is, cannot totally ensure the perfection of his or her transcription. Papyrus documents are fragmentary and lacunose, and the script can be highly cursive and therefore difficult to decipher. Things like orthography and syntax are usually below classical standards, sometimes far below, so it can be hard to understand what a text means. Throw into the mix the absence of context, poor word choice, and the occasional hapax legomenon, and one can appreciate the difficulty that goes into deciphering a papyrus document. Achieving full comprehension of any given witness can be a continual process involving more than one scholar over a long period of time. And many texts are never fully understood (Figure 2).

Metadata-Centric Tools

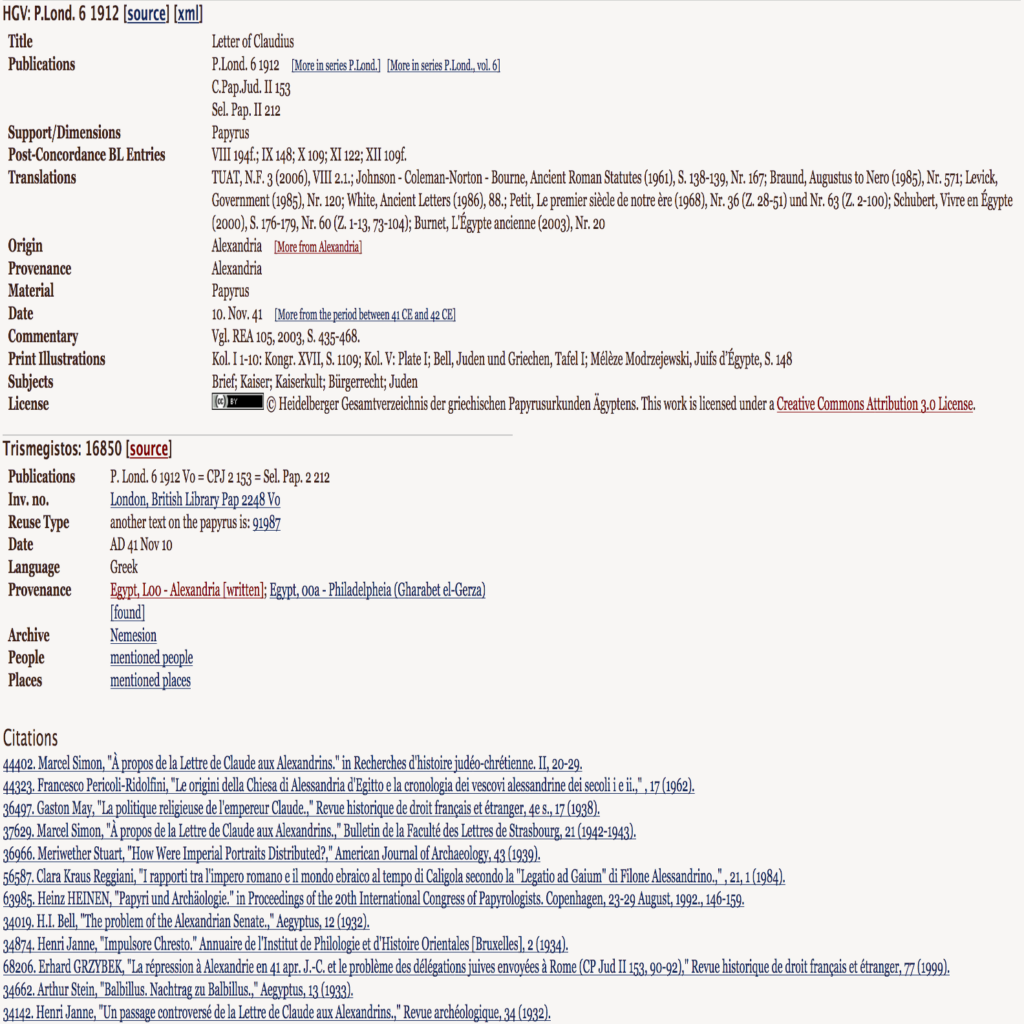

Metadata-centric tools developed along a parallel track to the Duke Databank. The Heidelberger Gesamtverzeichnis (HGV), which was started in the late 80s, and the more recent Trismegistos (TM) Texts, are two important examples of this genre. [10] They might be imagined as the curricula vitae of papyrological manuscripts (Figure 3).

Image-Centric Tools

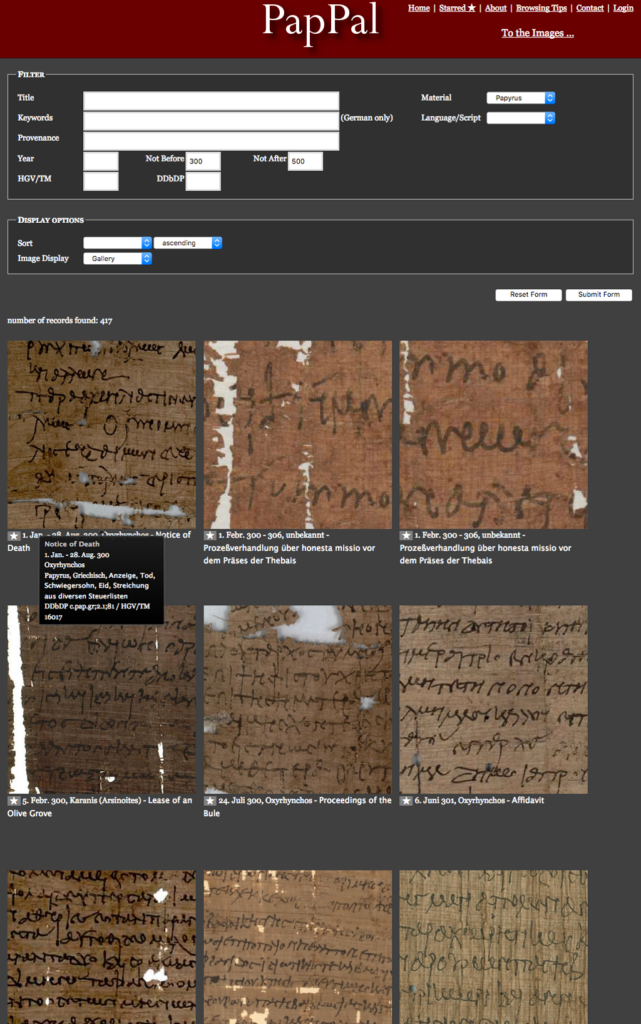

The third type of tool that has proved essential to our discipline is image-centric, and it has been the least exploited. Universities and museums have over the past two decades published thousands of photos online via a number of collection-based projects. Besides allowing papyrologists to verify readings or confirm physical connections between texts, which used to require significant time and cost, these projects have opened up new avenues for performing the same functions of discovery and comparison that text initiatives such as the Duke Databank have fostered. They have permitted researchers to start treating images like texts that can be mined and sorted. Sorting and comparing has been the goal of PapPal, for example, which gathers paleographical samples of dated documents (Figure 4). [12]

From Scholarly Aid to Curatorial Environment

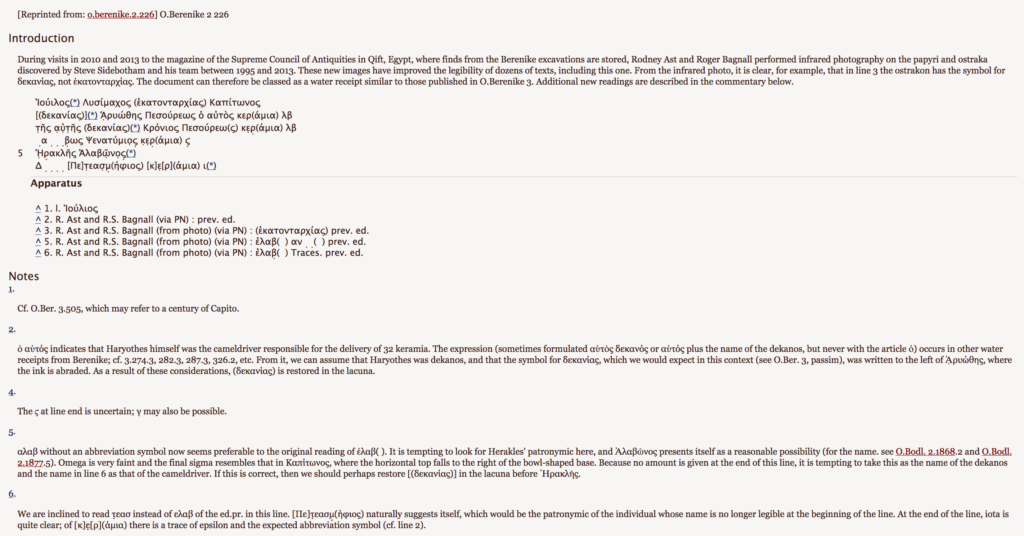

I will show you what I mean by a superior digital text with the example of an ostracon from the Red Sea harbor town of Berenike in Egypt’s Eastern Desert, which preserves a receipt for water delivery. It was originally published in the second volume of ostraca from Berenike (O.Berenike 2.226) under Miscellaneous, because the editors had not recognized it as a water receipt. After members of the Berenike project found dozens of similar texts in 2009, which Roger Bagnall and I published in the third volume of Berenike ostraca under the heading of Water Archive (O.Berenike 3.274–455), we realized that this earlier text was of a similar type. [16] Moreover, we could confirm this on the infrared photos. We were thus able to improve on the text of O.Berenike 2.226 enough that we created a substantially better digital edition. Because of our revisions, the text received an entirely new publication number, ddbdp;2016;2 (Figure 5). [17]