- Intertextuality is the relation between parallel text, in the form e.g. of quotation or allusion.

- Paratextuality is the relation between one text and what surrounds the main body of the text (e.g. titles, headings, and—we may add—graphical devices).

- Metatextuality is the explicit or implicit critical commentary of one text on another text.

- Hypotextuality/hypertextuality is the relation between a text and a preceding hypotext that is transformed, modified, elaborated or extended.

- Architextuality is the designation of a text as a part of a genre or genres.

Focusing now on the cultural products of ancient ‘medical literacy’, while bearing in mind the preceding scheme, we can outline the following main stages of use of reading/writing abilities and communications strategies, i.e. what is sociologically defined as ‘literacies’:

- Written scholarship, producing ‘literary’ treatises. The importance of the written text for ancient medical knowledge is stressed as earlier as in the Hippocratic corpus: “I consider the ability to evaluate correctly what has been written as an important part of the art,” says the author of the Epidemics, stressing however its instrumentality: “He who has knowledge of it and knows how to use it will not commit, in my opinion, serious errors in the professional practice” (Epid. III 16 K. = III 10, 7 ff. L.). [9] Papyrus witnesses of written treatises spread throughout the Hellenistic and Roman times, attesting to both known and unknown ancient medical scholarship. [10]

- Written teaching, performed by compilers producing manuals and handbooks, borrowing from elaborate treatises or other technical books (see below) and influencing, in turn, the following literature. [11]

- Oral teaching, producing hypomnemata (notes) later expanded in book format. In the introduction to the treatise On his own books, Galen himself explains how in the context of the oral lesson one used to take written notes, thence moving to the publication of memoranda that would become the hypomnemata of the lessons heard. [12] Orality also influenced the proper treatises. [13]

- Personal practice, producing annotations of various types. For instance Iatrika grammateia, “medical writings” on tablets (pinakia), [14] refer to the use of writing down the doctors’ personal annotations or clinical files in order to keep medical archives. [15] Some Hippocratic treatises (e.g. the Epidemics) exhibit a listthirddt fig1 here]]earbook 1989–s@mparison here?vious chapters do not. Remove?like format, in a raw syntax, being proper catalogues of diseases, symptoms, therapies, sometimes prognostics and aetiology, apparently derived from the physicians’ personal experience (i.e. from the clinical tablets or similar annotations) and serving as helpful guidelines for the future too. [16] The doctors’ personal practice was also at the origin of integrations and additions to existing treatises [17] and to pharmacological texts (see below and Bonati 2016, 65–66 for the latter instance).

- Textual transmission (the actual copying of physical books), producing interferences and variants. The ancient practice of collating several copies (antigrapha) of medical texts is attested above all by Galen, who noted several degrees of manuscript divergences, ranging from small linguistic variations to major discrepancies in the content, e.g. in the ingredients and quantities, [18] but we know of other cases in which the ancient readers produced “personal” copies that became, by means of reformulations and abbreviations, new recensions of the same text. [19] The fragmentary state of the papyri containing medical texts is an exacerbated form of interference where physical damages and linguistic variations condition the state of the original text. [20]

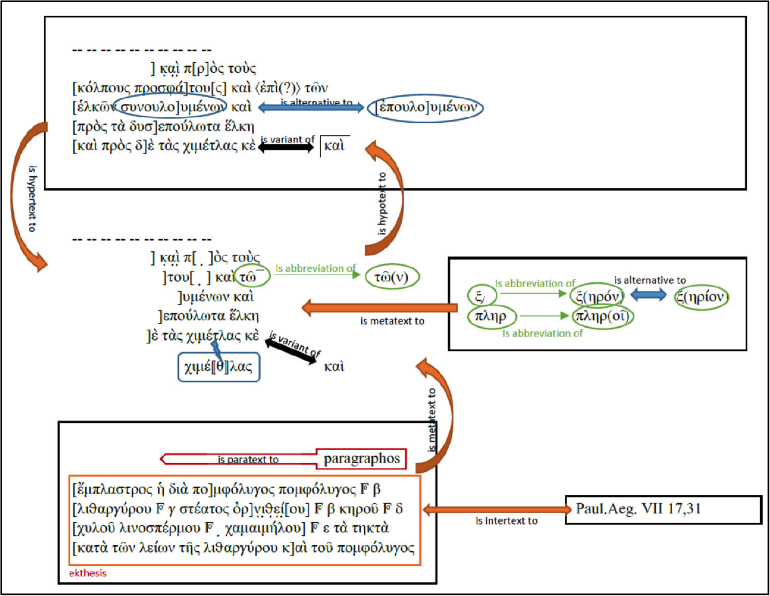

Each one of the abovementioned stages is deeply interrelated with the others. One main transtextual connection is given by intertextuality, i.e. direct or indirect quotations: for example, most of the late antique medical literature is represented by compediasts (Oribasius, Aetius, Paulus of Aegina) who took and interwove excerpts from the earlier authors in order to create composite texts, with the purpose of assembling the best from previous writings. [21] Yet there are paratextual, metatextual, and hypotextual devices that characterise ancient medical writings as technical texts in flux and that clarify the concept of “ancient medical literacies.” The older treatises are annotated, commented, collated often against annotated and commented copies, [22] transcribed with additions, corrections, and updates; the collections of personal notes on clinical cases, therapies or remedies are constantly revised on the ground of practice; prescriptions are transcribed, gathered in the receptaria and passed down; handbooks of different typologies are used to teach again, and so on, keeping written trace of every stage of transmission and use, even of the oral one. Moreover, each transtextual link is deeply rooted in the very meaning of the text itself, which means that the medical texts cannot be understood and appreciated without considering this complex network of connections. [23] Let us take Ann Hanson’s specimina (being both as widespread and basic as technical enough to be perfectly representatives of the ancient ‘medical literacies’) and try to consider them from the perspective of Genette’s textual theory.

Intertextuality, hypotextuality and similar connections merge together, creating a very complex and unique clockwork: “although individual recipes in a collection on papyrus often resemble items in the known authors, each extensive collection on papyrus has thus far proved to be a unique assemblage.” [37] The paratextual function of critical and lectional marks stresses the “composite” structure of the text, acting as a bridge between its oral roots and its later outcomes. [38]

Archaic epic is of course an extreme case. In Albert Lord’s words,

Mutatis mutandis, these considerations apply to ancient medicine, an oral knowledge intertwined with practical know-how and with a deep and complex relationship with writing, and even more to ancient medical texts preserved on papyrus, which attest to a much wider variety of technical, specialised writings. A multitext model, after all, is being successfully applied to different textual traditions than the mere Homeric poetry: namely, the fragments of the ancient historians. [49] Given the fragmentation of ancient medical writings on papyrus, [50] this is an interesting and suitable precedent. According to Monica Berti,

This paradigm can be easily exported to the case of Greek medical papyri, [52] provided that most of the infrastructures (markup, metadata) are already available through the existing and the forthcoming papyrological platforms.