1. Challenges of application of IT in Humanities

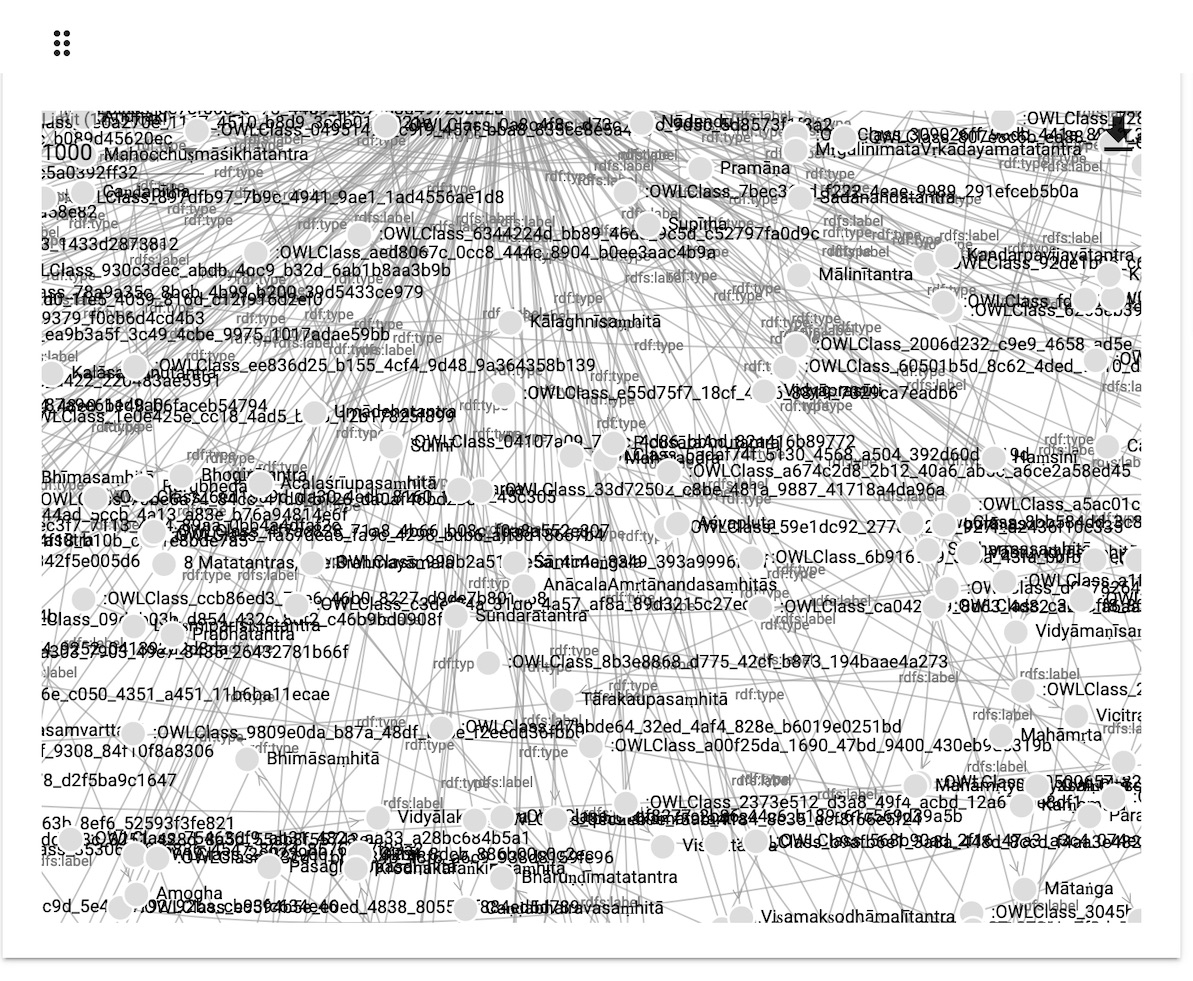

To redress this situation, the humanities should start to follow the path of “precise sciences,” [3] with their strong emphases like collaborative character of research, the main actor is not a scholar versus a source text, but a team of scholars including IT versus the totality of the available data, of which the most relevant is chosen, not retyping the pieces of texts, but querying the databases, and not writing one more “stone,” but redefining the discipline’s ontologies in the global linked data (Figures 1 and 2):

2. Existing IT solutions for Digital Humanities in Switzerland and some successful projects

3. NIE-INE and its product Inseri as an innovative response to the open challenges

How does it all change the way people do DH? To demonstrate the data flow and reuse in the humanities, the following two pictures were prepared (Figures 3 and 4). The first is the “traditional data flow” and the second is a data flow within NIE-INE, based on Inseri and SWT. In the traditional mode (Figure 3), the final product of the scientific work is not different by its very nature from the original input, i.e. a text source.

This very philosophy has naturally grown within NIE-INE and Inseri (Figure 4), where the IT solutions and databases are reused. Each project contributes also to the IT development by providing the questions and the problems and commenting on the proposed solutions.

4. Case Study: Stages of a manuscript-based academic project within the Inseri framework

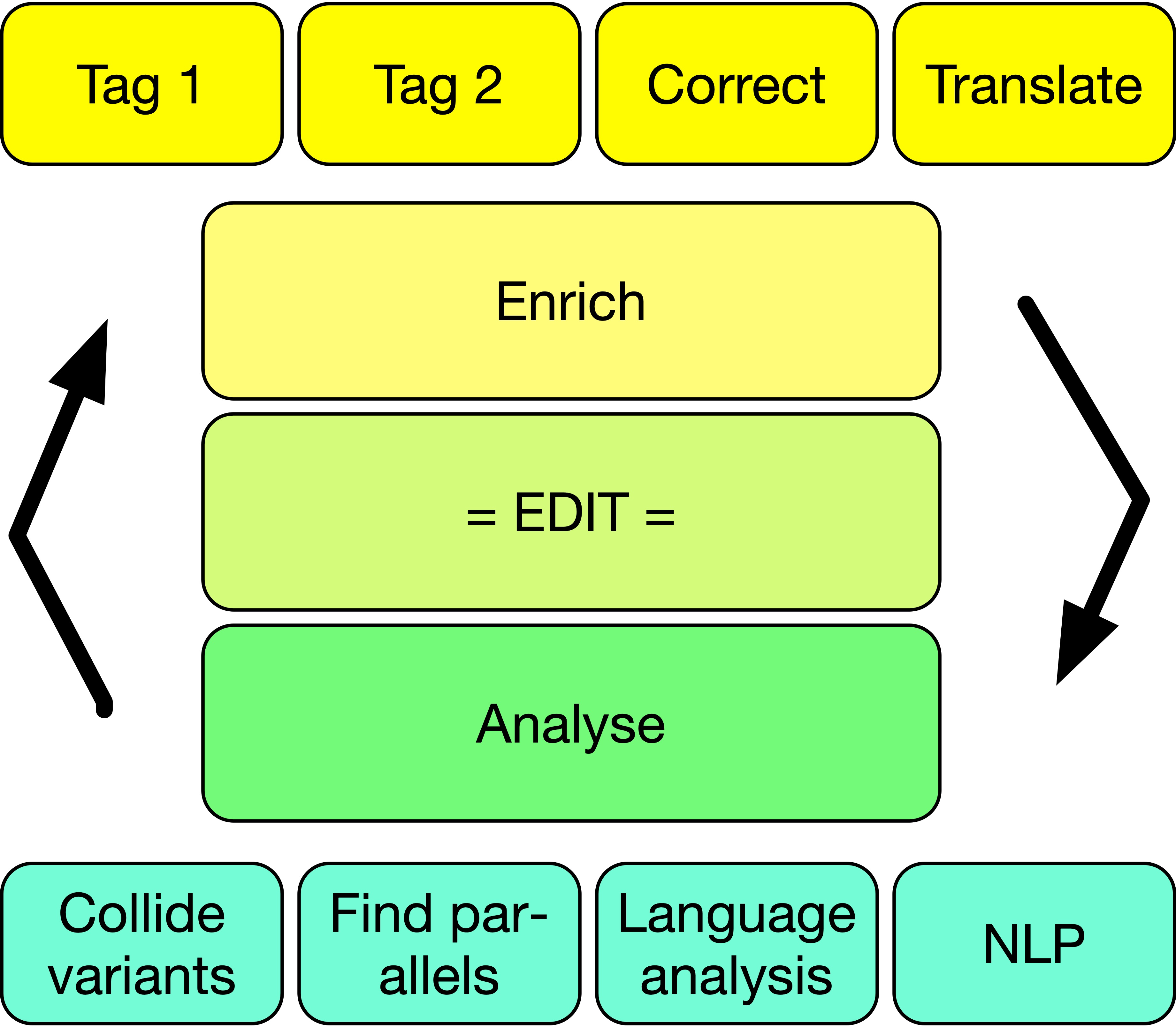

The whole workflow is divided into seven distinct areas (Figure 5). The project might use all seven or only a few. These areas are conceived in such a way as to cover the totality of the academic work, from raw data collection, analysis, and, finally, publication. What follows shall be described in a view to implement Semantic Web Technology, which requires multiple preparatory steps, namely data conversion into RDF.

Sample procedure, A-Z in a few examples

Step 1. Data collection

Inseri provides both the query options if the resources are available online, for example IIIF or any other data with RESTful APIs, such as ARKs, and the simple upload from the user’s desktop. There are about 70 templates already available to query various IIIF institutions. The scholar can work, for instance, with millions of scanned manuscripts pages directly from within the Inseri project by changing a single URL (Figure 6.1). [24]

The environment is similar to that of IIIF viewers but can be fully customised. The user can navigate from page via the arrows in the bottom-left corner of the apps (Figure 6.2) or by using an extended search to have an overview of all pages of the manuscript (Figure 6.3).

Step 2. Administration

Step 3. Enrich Data

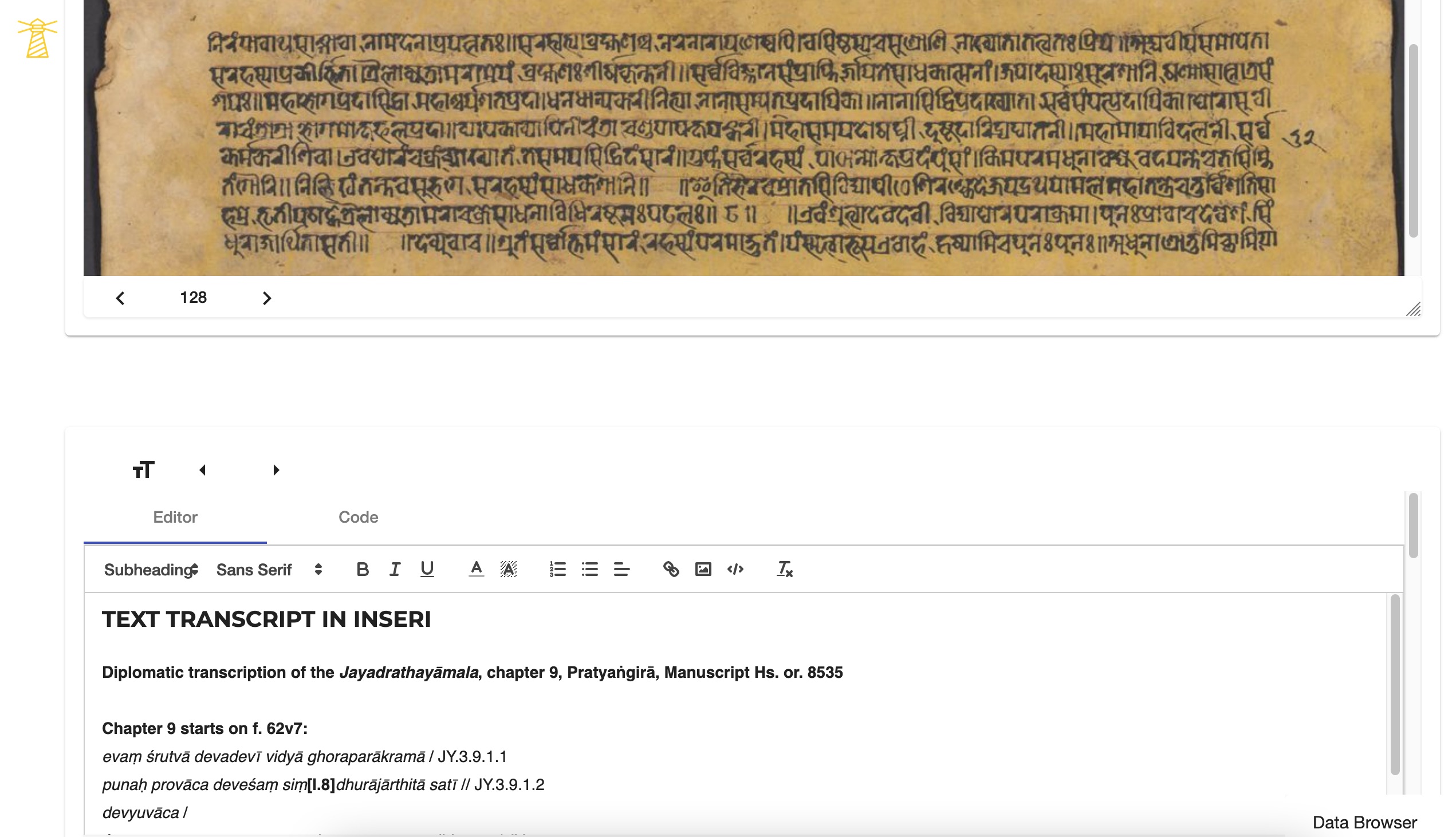

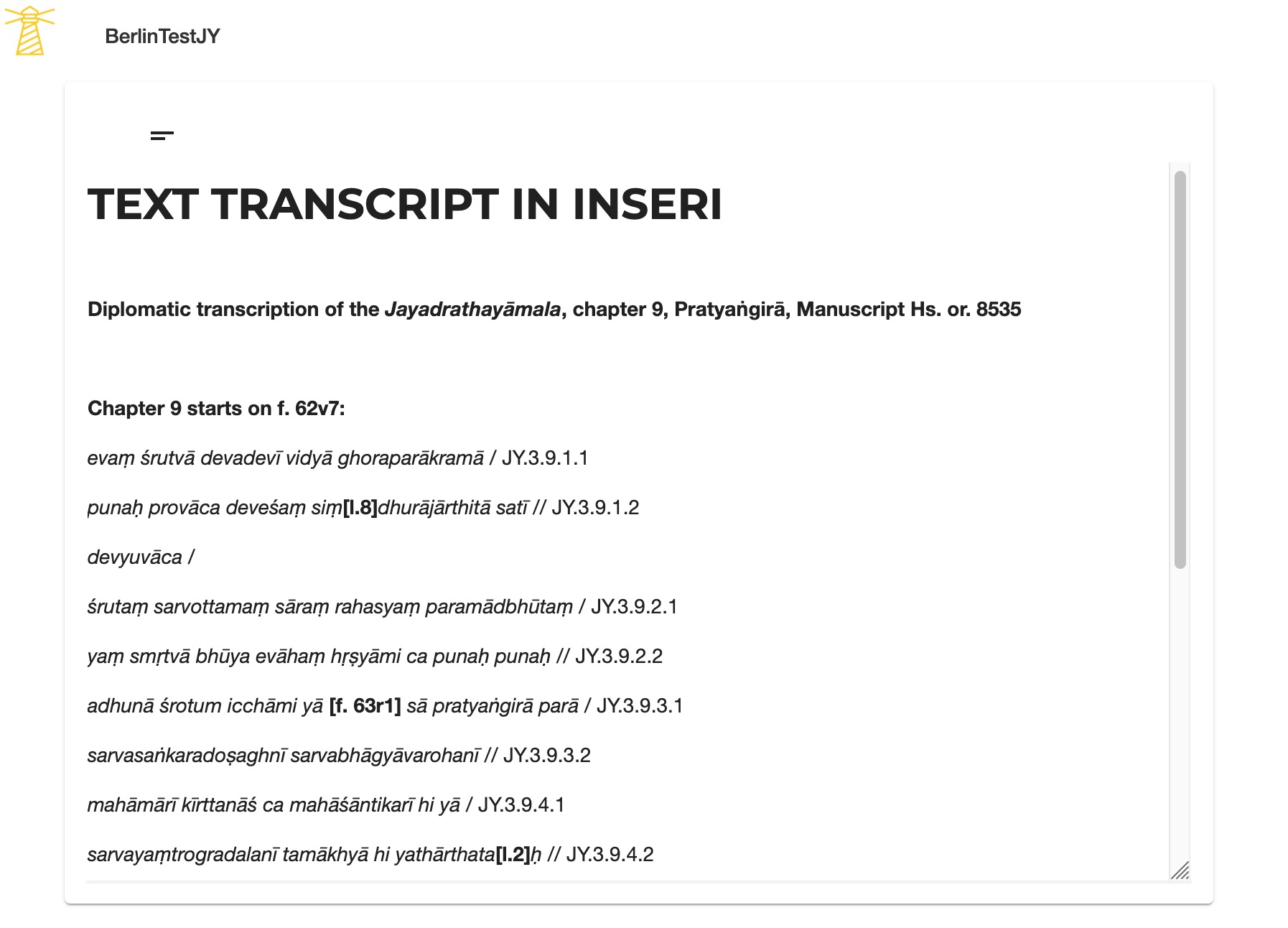

Here the “raw data” (images, for example) in various formats is transformed into stable and clean data (transcribed texts), ready for manual, semi-automatic, and automatic analysis. [25] For the transcript the Text Editor app was used (Figure 7.1).

The Plaintext Viewer app enables the publication of the transcript immediately on the Inseri page (Figure 7.2). In the enrichment part we can also tag according to TEI standards all geographical names, references to kings, time and place, religious traditions, names of people and names of other texts, according to the specificity of the text and planned analysis. [26] When those selected entries are indexed, they are linked to a widely acceptable spelling of proper names and, whenever possible, linked to external data, for example GND and other “authority databases,” including those complied by the projects. All that directly contributes to Linked Data, besides helping to define with precision the date, provenance, and the position of the text being edited.

Only having done this resource preparation, we can already begin to speak about an edition proper. Edition is a process involving two aspects of working with the text: the enrichment via tagging and refining via analysis (Figure 7.3). Both processes lead to corrections, conjectures, and reformulations of the notes; thus the final text cannot be produced until the necessary number of the upgrading rounds has been completed. [27]

Step 4. Data Analysis

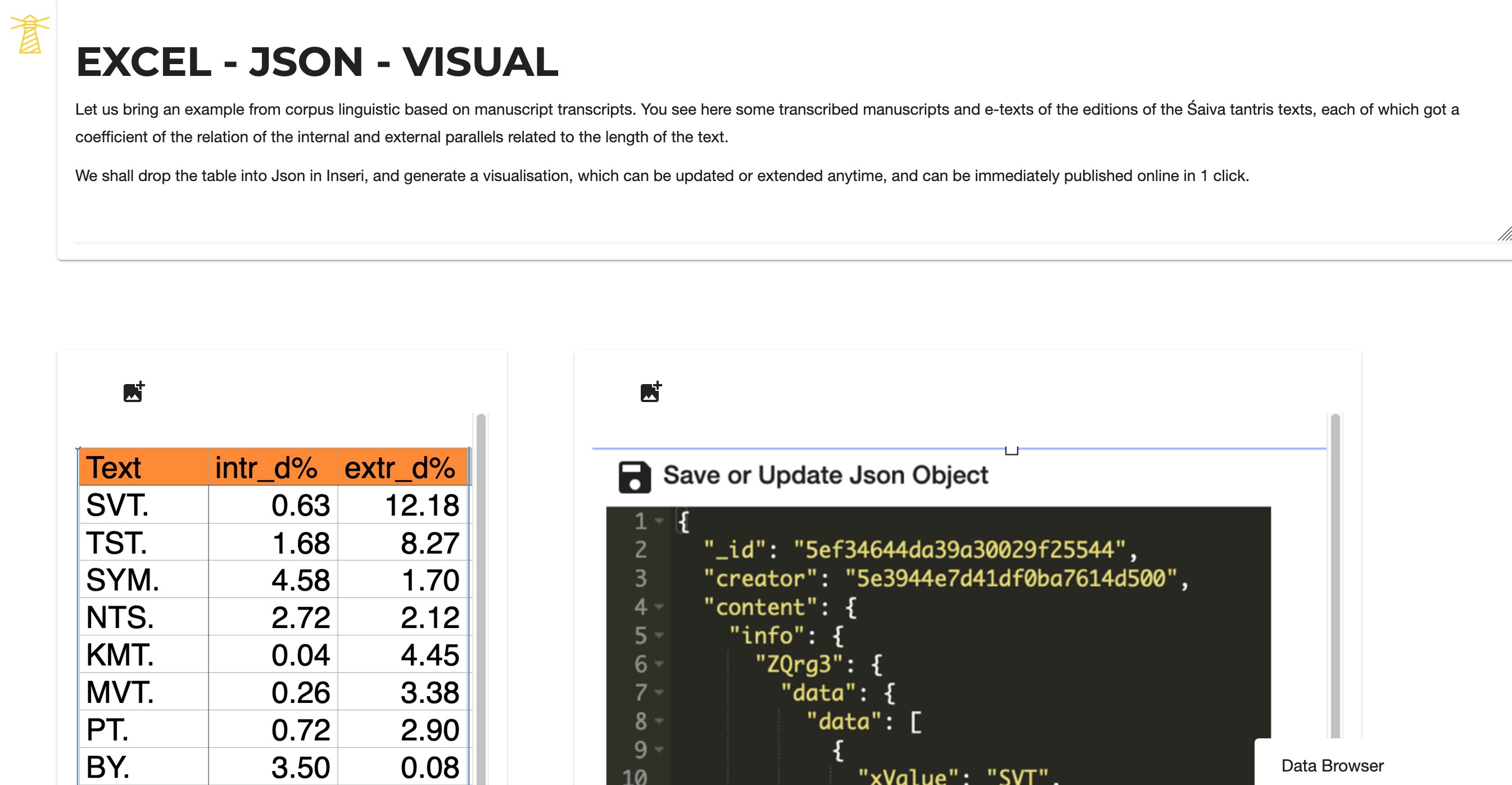

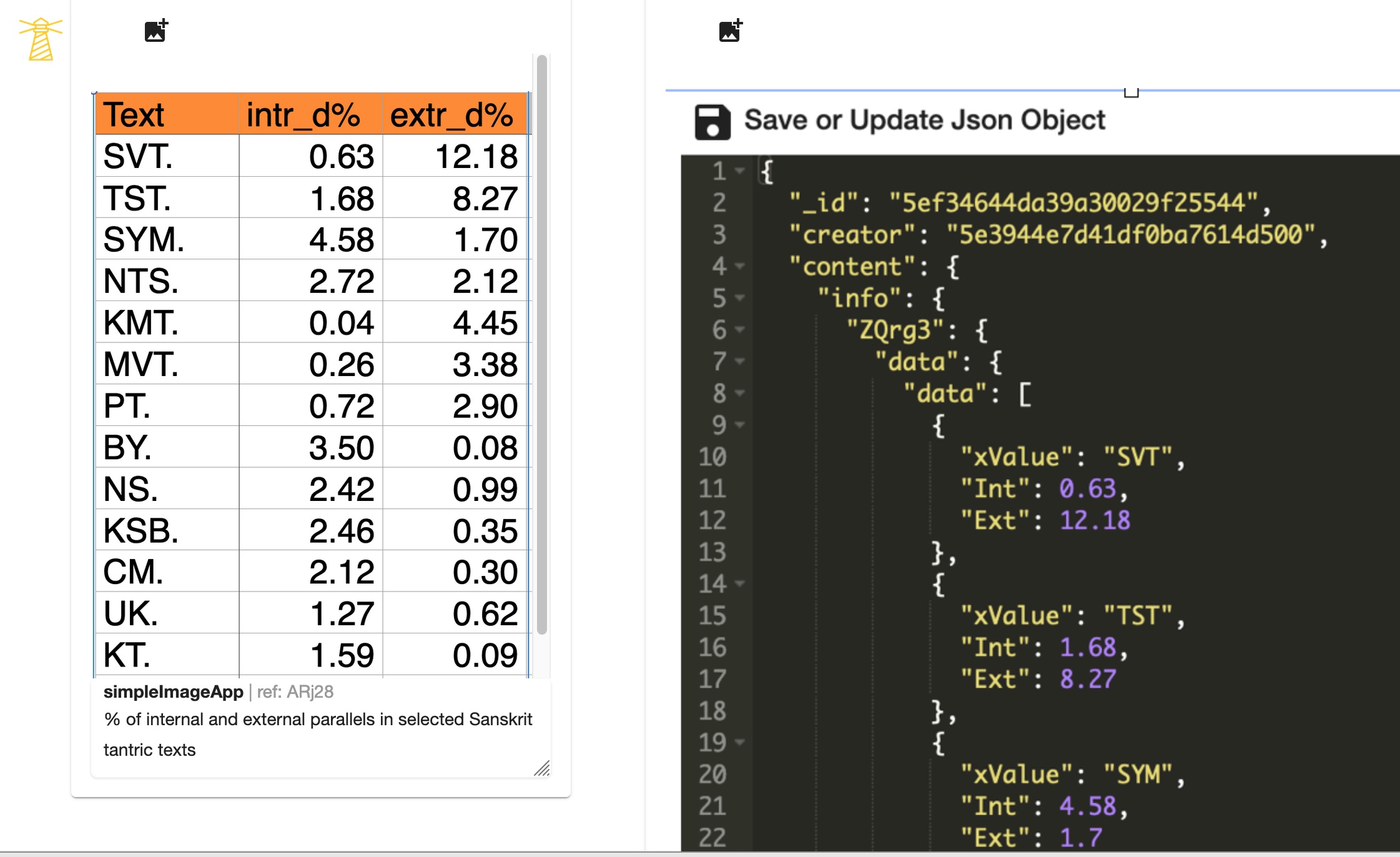

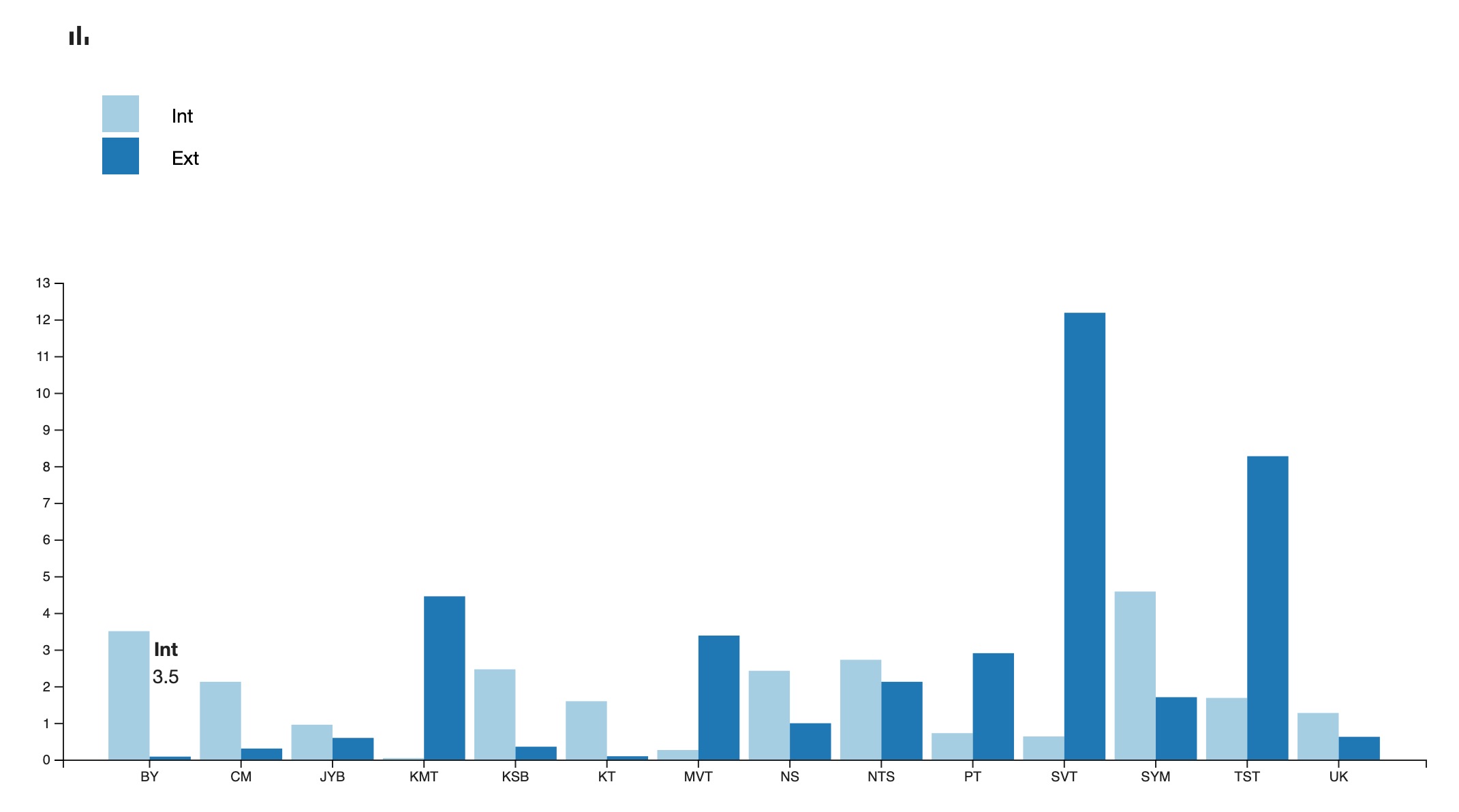

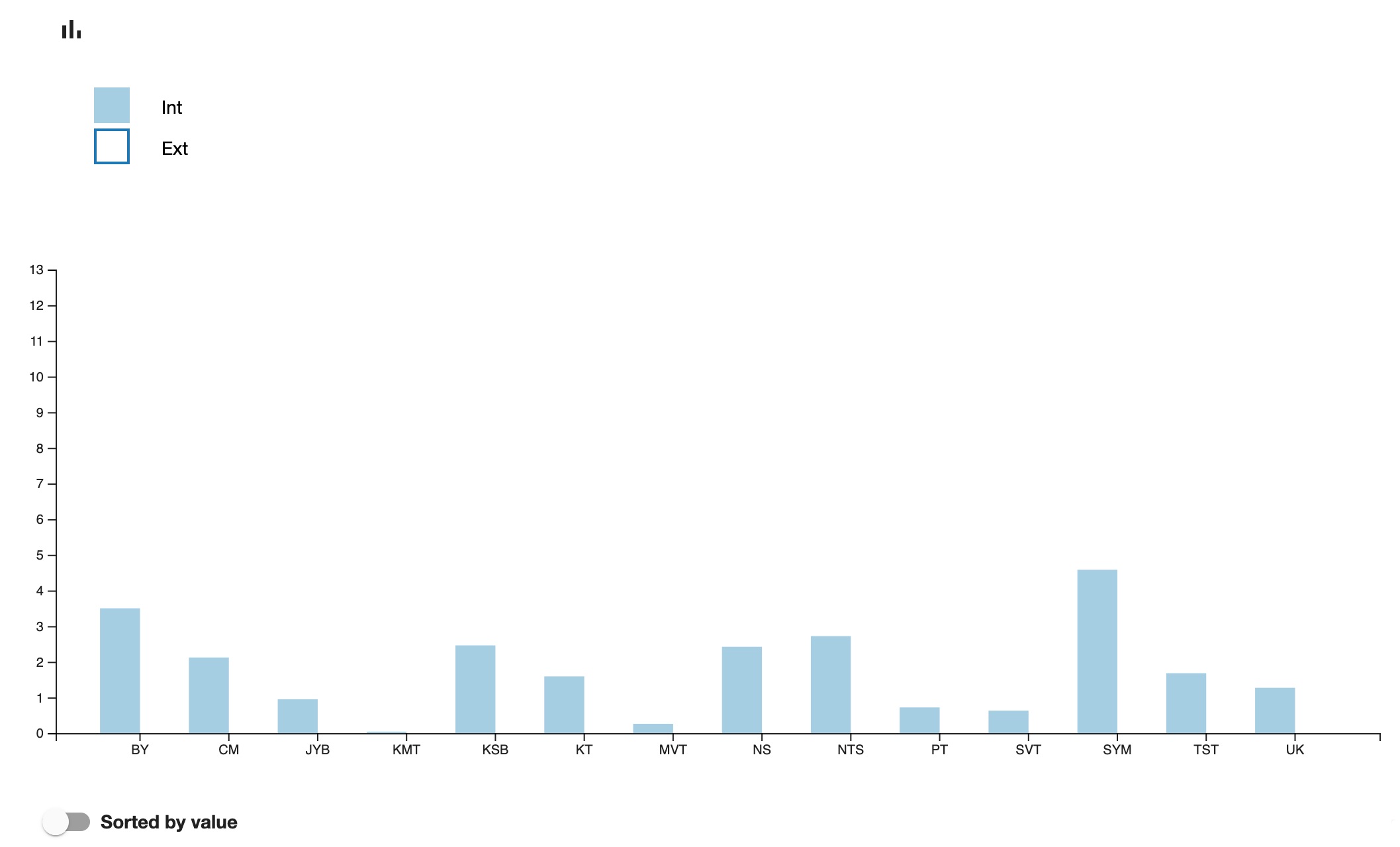

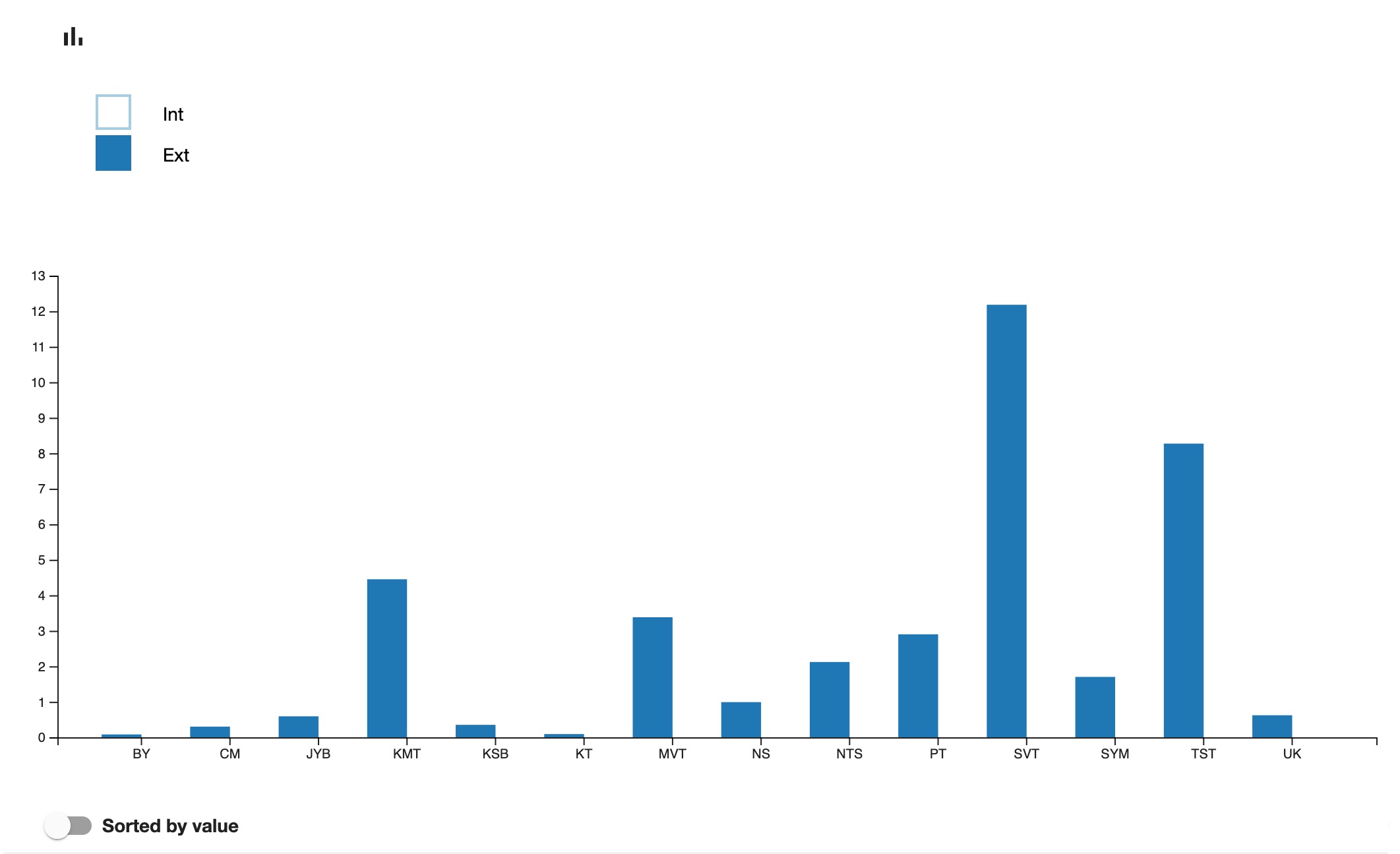

For the Sanskrit Manuscripts Project, I have tested the visualisation within Inseri of the result obtained outside of it (with R). The results of comparison of the 29 Sanskrit texts in relation to their internal and external parallels related to their length and thus expressed as coefficients, were originally stored in Excel. This was converted into JSON, and pasted into Inseri, immediately enabling us to obtain dynamic visualisation (Figures 8.1–4).

Step 5. Visualisations

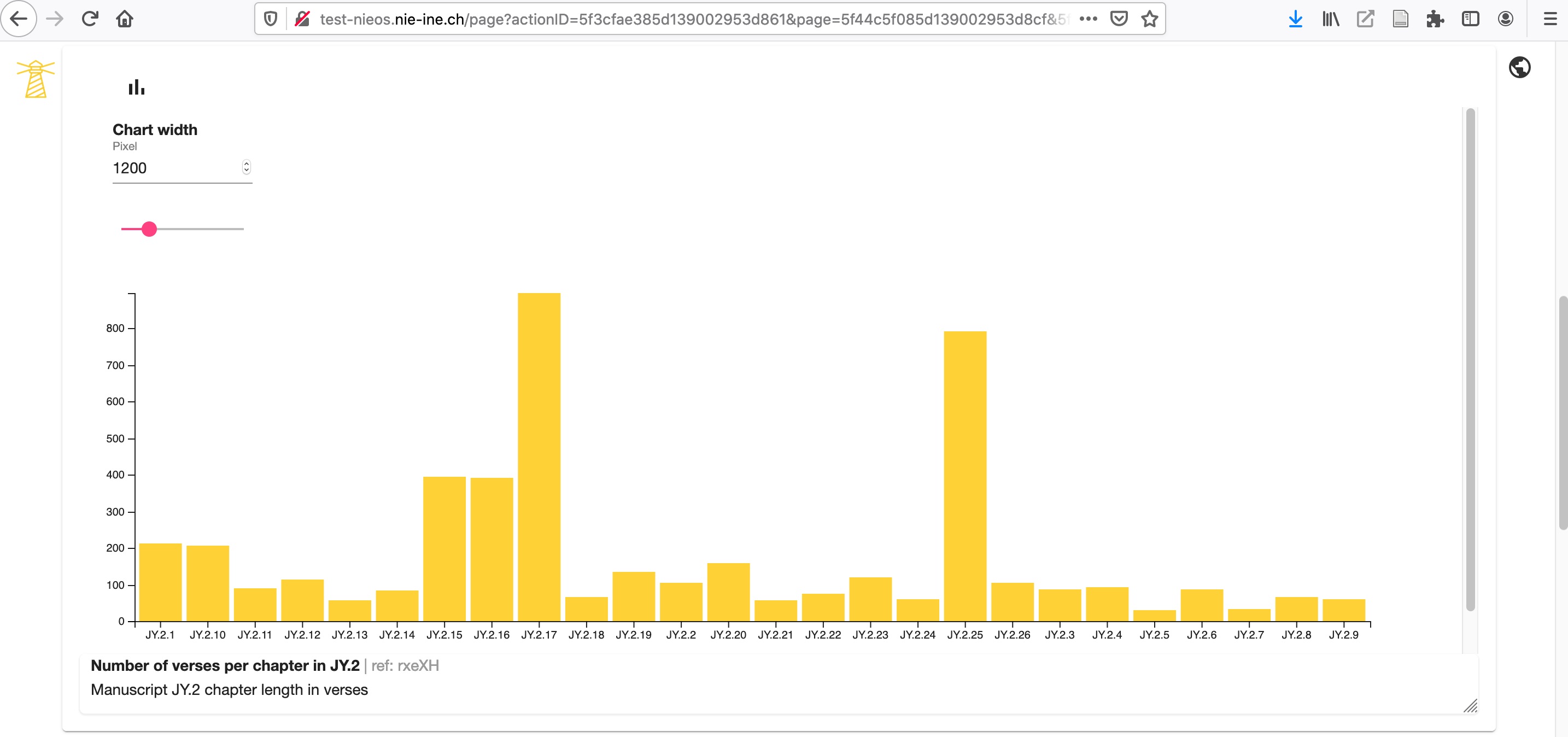

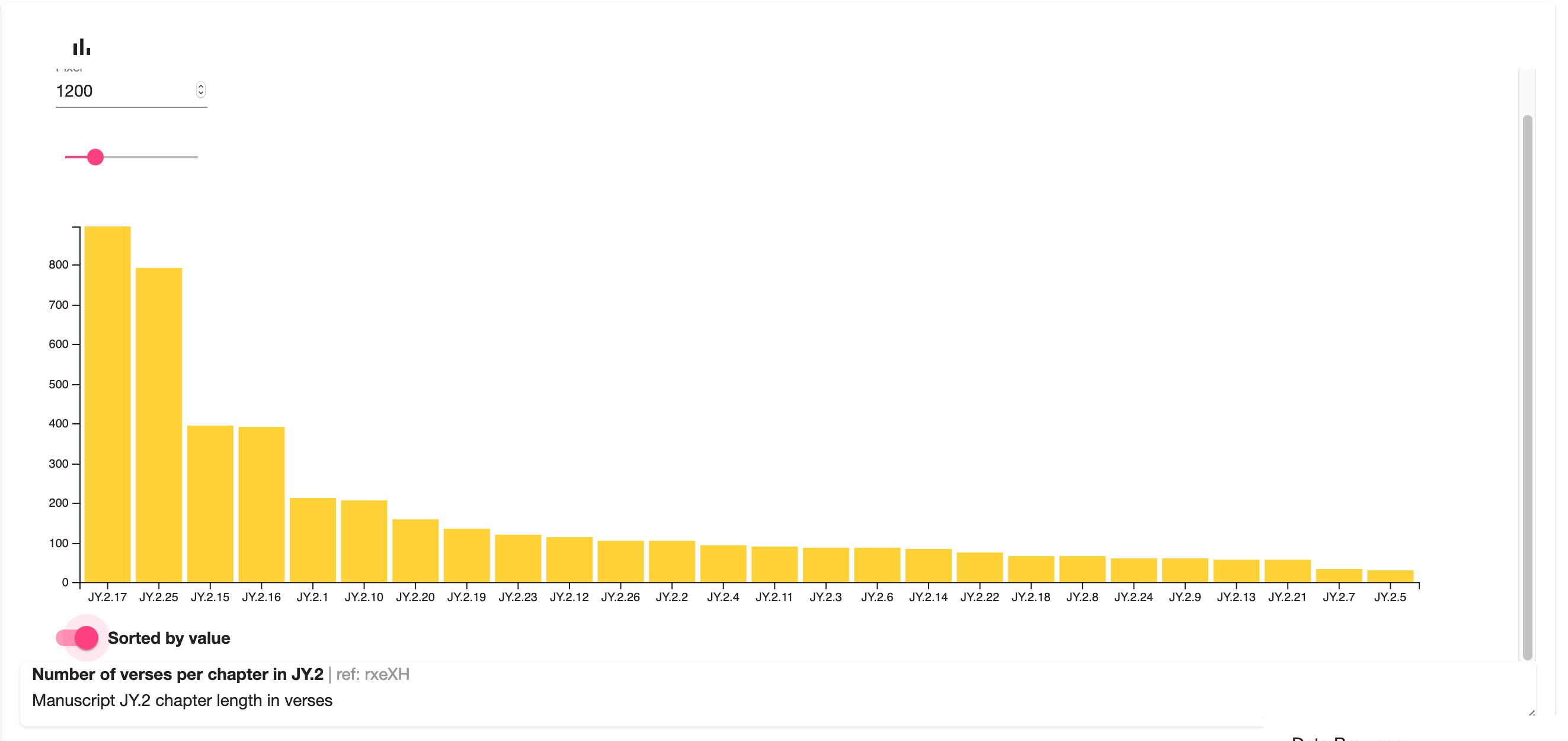

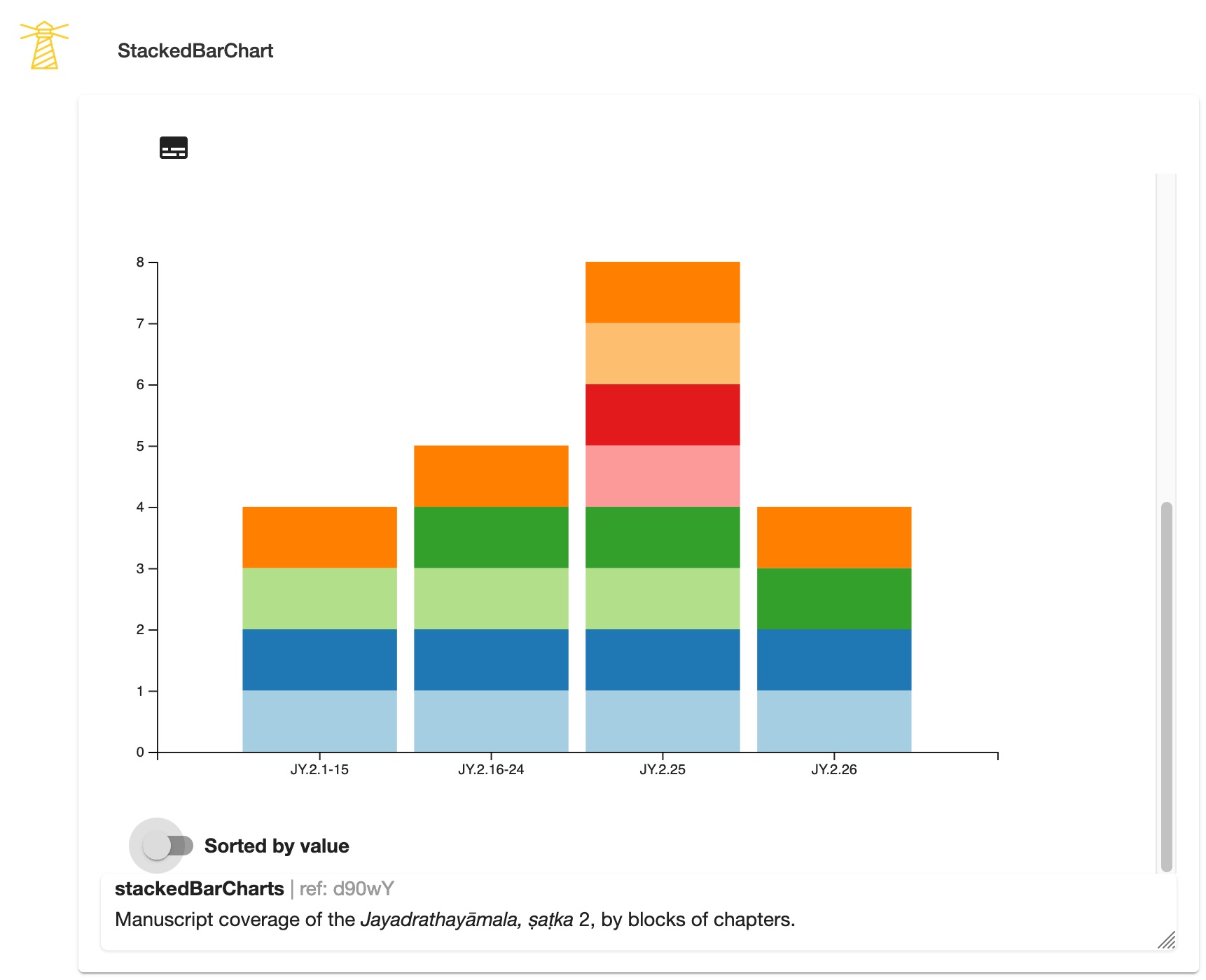

Let us provide two simple examples of visualisations (Figures 9.1.1–2 and 9.2.1–2). It is a visual representation of the length of the chapters in verses, and of the manuscript coverage of the same text, Jayadrathayāmala, ṣaṭka 2, both of which can be easily sorted by value.

Step 6. Semantic Web Technology and machine reasoning

Step 7. Sharing the project results, publishing

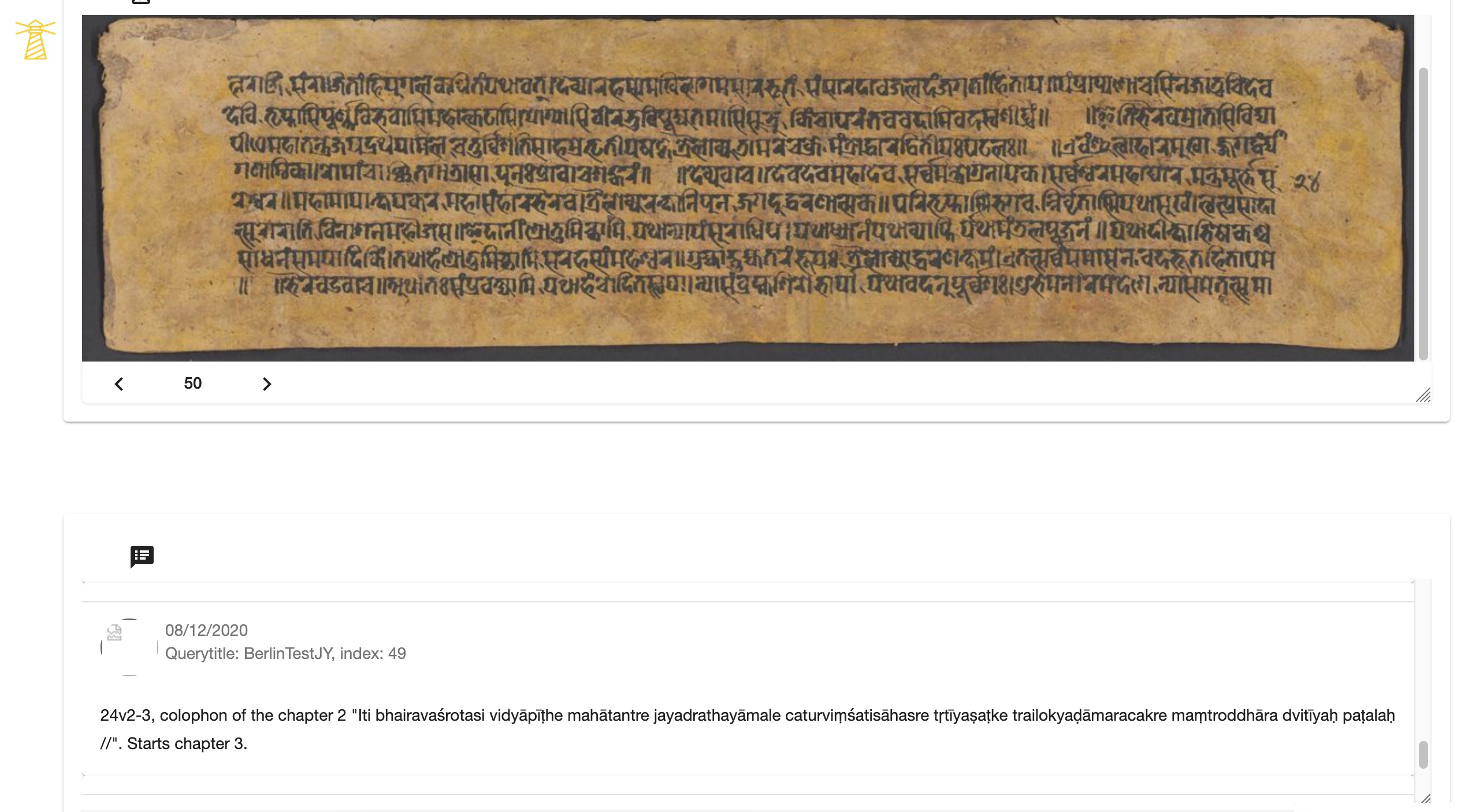

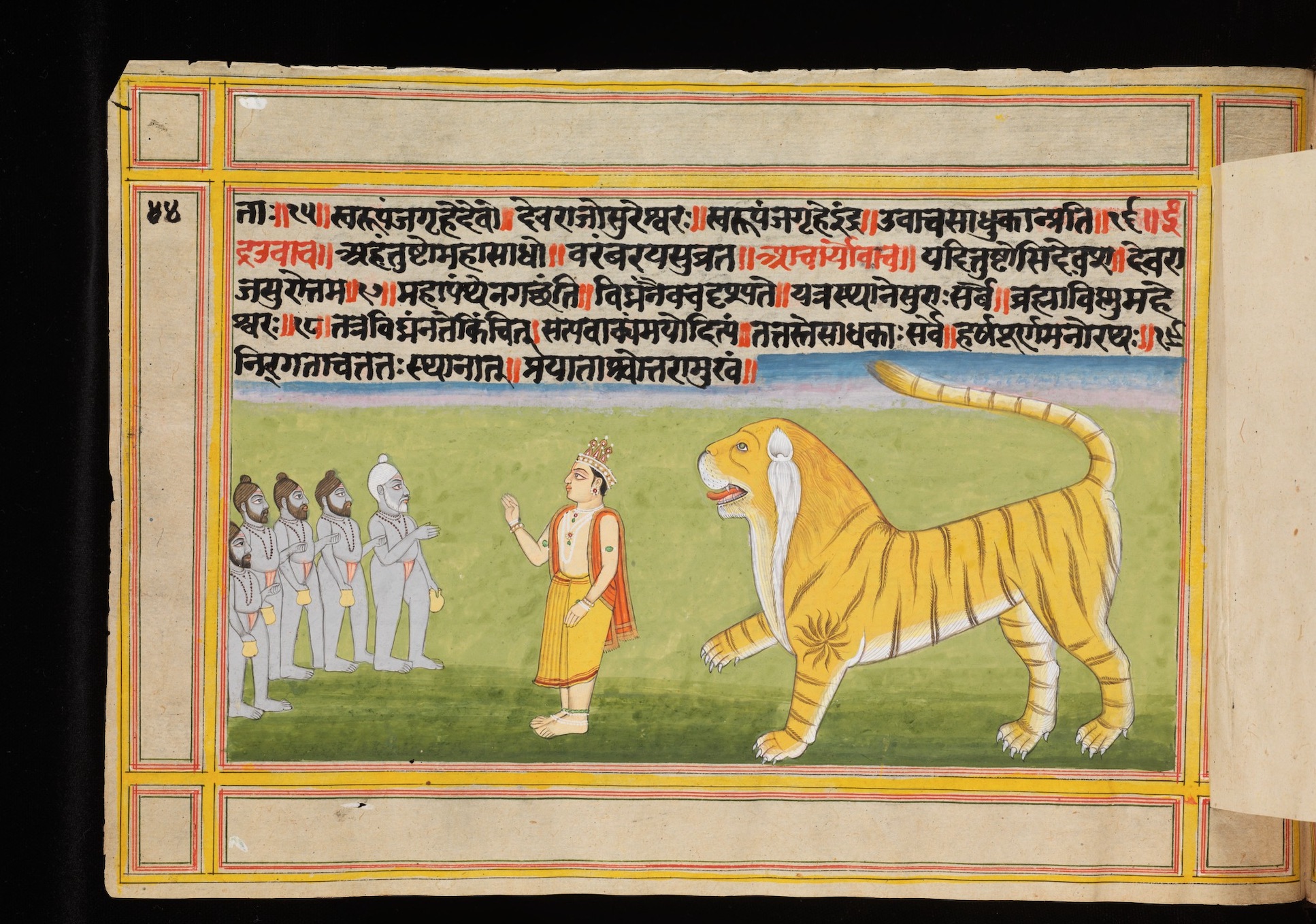

Here is an example of a complicated web page layout bringing together the query to IIIF (E-codices), the image (Figure 11), and a description of the image made by a researcher. [35] The globe sign in the top-right corner signifies that the page has been published. The scholar can thus combine the “tiles” containing the materials from different provenance and of various formats with utmost ease.

5. A new academic paradigm in the humanities?

Figure 12 is a simplified representation of the Inseri Framework, as of October 2020, adapted to edition projects, but it can virtually incorporate any research project regardless of the discipline. Only minimal details and interconnections are given here, and the full arrow line stand for the existing and working connections, while the dotted and other incomplete lines represent areas for further development.