Simone Zenzaro

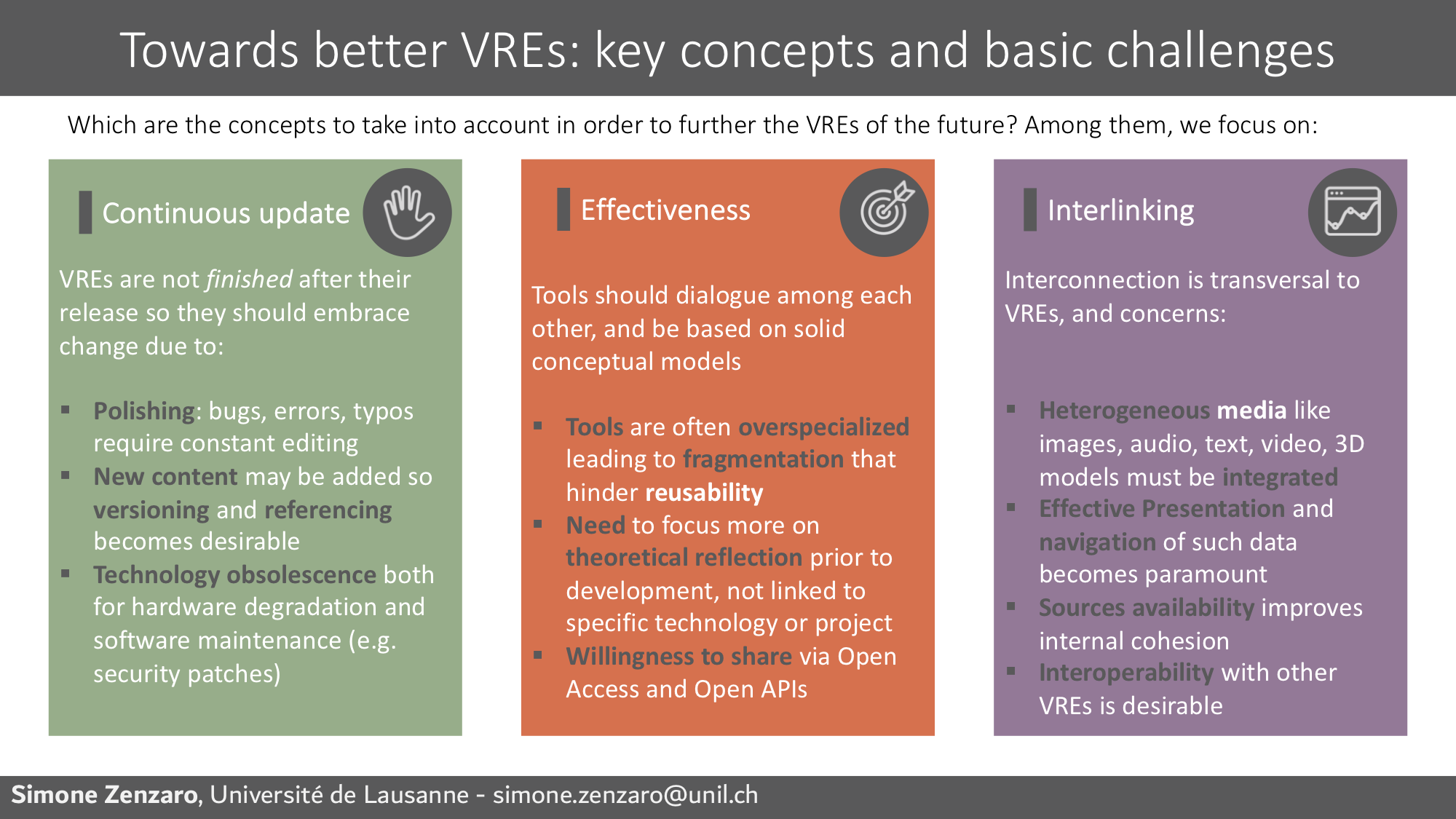

Improving the current state of Virtual Research Environments (VREs) requires to address the growing complexity of their design and development. To this extent, the focused awareness on three fundamental aspects of VRE design mitigates the difficulties of such a challenge. These features are: continuous update, effectiveness, and interlinking. Since these aspects are deeply interconnected with one another they should be addressed simultaneously.

1. Introduction

Virtual Research Environments are complex artifacts with respect to both their production and their subsequent use. [1] As many have noted, [2] lots of interesting projects involving VREs have been developed, [3] but there are several universal topics that require attention if we want VREs to develop further as research tools. To further the current state of Virtual Research Environments is not due to technological limits but it is a methodological matter. Although we are only scratching the surface of what is possible to achieve with VREs, and in spite of many attempts to find shared frameworks and definitions, [4] VREs, in their current situation, are being used in very diverse contexts making the task of approaching VRE design complex. However, we would like to focus on three aspects in VRE design that should help the development of future VREs: continuous update, effectiveness, and interlinking. By focusing, from the very beginning of the production of a VRE on these three concepts, and by addressing them at the same time (since they are strictly intertwined), we will encourage a change of perspective from a project-centric to a sharing and reusability-centric approach to digital tools.

2. Concepts

In the following section I will briefly introduce the three concepts of continuous update, effectiveness, and interlinking, and give some context about their importance. Since the term VRE is very broad, not every aspect or proposed direction may be immediately applicable. Moreover, most of the following content is biased toward IT approaches that might be beneficial to VREs in the humanities.

2.1. Continuous Update

Scholars usually tend to consider VREs finished after their release. However, since changes will come in the form of polishing or fixing errors, of new content to be added, or of technology obsolescence, VRE should embrace the possibility of continuous update and maintenance. From this point of view, the design of a VRE should be easily updatable and extensible creating a situation where multiple versions of the same VRE will be produced. Moreover, since the VREs are also meant to be a place for sharing research, it becomes crucial to equip future VREs with version control systems and standard means to reference each version. First steps toward this goal may borrow the consolidated approaches already in use in the IT field of tracking changes in the history of a VRE by applying a unique version tag that follows semantic restrictions as with SemVer. [5] Another, more demanding approach would be to adapt the well-known structure of control systems (such as GIT [6] ) combining it with URN [7] names in order to standardize the way it is possible to reference VREs content.

2.2. Effectiveness

In terms of VRE effectiveness, I would like to focus on two different directions: a methodological and an interpersonal one. When IT methods and tools are adopted hastily disregarding [8] the lessons of decades of software engineering, [9] the resulting tools ecosystem becomes fragmented and not as interoperable as it could be. Usually the inter-tool communication is hindered by the over-specialization of such tools; that also hampers their potential reuse for even slightly different purposes from the one the tool has been created for. For example, this may happen, as also mentioned by Dunn, [10] if the data entry tools do not specify how to deal with the interpretative level for such data. In this sense, deeper theoretical reflection, unanchored to specific technologies and prior to development, should be considered since overvaluing a specific technology has another drawback: obsolescence. The exploitation or creation of ontologies for the fundamental concepts of a VRE represents a first step toward a solution as it has been attempted before (e.g. by Gladun [11] or in e-ditiones [12] ). The effectiveness of VREs can also be improved by focusing on the willingness to share content and research results. Producing shareable artifacts via Open APIs [13] and Open access [14] will mitigate the drawbacks of the usual approaches and pave the way to build upon each other’s work. From the inter-personal point of view, my experience confirms the proposal of a paradigm shift from needy-user to explorability. [15] Although it may seem obvious, by cultivating an effective and respectful communication among persons with very distant backgrounds produces far better results. [16] When interpersonal communication is not sufficiently considered, the consequent misunderstandings and misinterpretations will see the proliferation of ineffective tools.

2.3. Interlinking

When interlinked [17] a VRE addresses the impulse toward better presentation systems [18] and the interoperability concerns. A vast set of heterogeneous media (images, texts, audio, videos, 3D models, even other VREs) can comprise parts of complex VREs; the task of integrating them together is not easy and requires careful evaluation of which kind of interaction is suitable for seamless navigation of the VRE contents. [19] Moreover, the content of a VRE usually refers to external resources in various forms such as external links (potentially toward other VREs), content delivery networks (e.g. IIIF servers [20] ), or even internal references. [21] While an external resource brings benefits to the VRE, it also represents a point of failure in case the referred resource is moved or is unavailable. Future VREs should consider mechanisms to check (possibly automatically) missing resources in order to fix broken links or update the content. [22] On the other side of the coin VREs would benefit from decoupling the presentation system from its content. This way, the interoperability between VREs would dramatically improve and lead to better reuse of the knowledge base related to VREs.

In the humanities area, there are indeed fields in which the decoupling process may appear unnatural since data and their presentation coexist (for example the critical apparatus of a critical edition may define cosmetic notation linked to semantics like using bold stylized texts to denote witnesses).

3. Conclusions

In this short study, I have presented three large areas of interest for consideration when creating a VRE: continuous update, effectiveness, interlinking. Each of these aspects takes a different point of view about what can be done in order to further the development of the future VREs. Considering each of them singularly might be beneficial to the resulting VRE, nevertheless, since they are interconnected with one another, I suggest, when possible, to address them simultaneously in order to produce maximal synergy.

Bibliography

Assante, M., et al. 2011. “An approach to virtual research environment user interfaces dynamic construction.” In Research and Advanced Technology for Digital Libraries: International Conference on Theory and Practice of Digital Libraries; TPDL 2011, Berlin, Germany, September 26–28, 2011; Proceedings, ed. S. Gradmann et al., 101–109. Berlin and Heidelberg.

Börger, E. 2010. “The abstract state machines method for high-level system design and analysis.” In Formal Methods: State of the Art and New Directions, ed. P. Boca, J. Bowen, and J. Siddiqi, 79–116. London.

Björneborn, L. 2017. “Three Key Affordances for Serendipity: Toward a Framework Connecting Environmental and Personal Factors in Serendipitous Encounters.” Journal of Documentation 73(5):1053–1081.

Carusi, A., and T. Reimer. 2010. Virtual Research Environment Collaborative Landscape Study. JISC. Bristol. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.404.6517&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Dunn, S. 2009. “Dealing with the complexity deluge: VREs in the arts and humanities.” Library Hi Tech 27(2):205–216. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/07378830910968164.

Gladun, A., et al. 2015. “Ontology-based knowledge recognition in service-oriented virtual research environments; Case: application in e-learning.” In ICIT 2015: The 7th International Conference on Information Technology, ed. A. Al-Dahoud et al., 148–155. Amman. http://icit.zuj.edu.jo/ICIT15/.

Jackson, M. 2001. Problem frames: analysing and structuring software development problems. Harlow.

Oldmann, D., et al. 2014. “Realizing lessons of the last 20 years: A manifesto for data provisioning & aggregation services for the digital humanities (a position paper).” D-Lib Magazine 20(7/8).

Popitsch, N. P., and B. Haslhofer. 2010. “DSNotify: handling broken links in the web of data.” In Proceedings of the 19th international conference on World wide web (WWW ’10), ed. M. Rappa and P. Jones, 761–770. Raleigh. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/1772690.1772768.

Procter, R., et al. 2011. “Agile project management: a case study of a virtual research environment development project.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work 20:197–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-011-9137-z.

Remy, L., et al. 2019. Building an integrated enhanced virtual research environment metadata catalogue. Geneva. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3497056.

Sabir, F., and V. P. Engerer. 2019. “The Prior eArchive as virtual research environment: towards serendipity and explorability.” In Logic and Philosophy of Time. Vol. 2, Further Themes from Prior, ed. P. Blackburn, P. Hasle, and P. Øhrstrøm, 201–230. Aalborg.

Sarwar, M. S., et al. 2010. “Towards a Virtual Research Environment for Language and Literature Researchers.” In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Sixth International Conference on e-Science, ed. P. Roe et al., 33–40. Washington, DC, and Los Alamitos. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/eScience.2010.37.

Schindler, C. et al. 2012. “Intra-linking the Research Corpus. Using Semantic MediaWiki as a lightweight Virtual Research Environment.” In Digital Humanities 2012, ed. J. C. Meister et al., 359–362. Hamburg.

Suber P. 2012. Open access overview. Cambridge.

Footnotes

Dunn 2009.

Oldmann et al. 2014.

[ back ] 3. Procter et al. 2011; Remy et al. 2019; Sarwar et al. 2010; Schindler et al. 2012.

[ back ] 4. Carusi and Reimer 2010.

[ back ] 8. Although this can be due to time or budget constraints and not to a deliberate choice.

[ back ] 9. Jackson 2001; Börger 2010.

[ back ] 10. Dunn 2009.

[ back ] 11. Gladun et al. 2015.

[ back ] 14. Suber 2012.

[ back ] 15. Sabir and Engerer 2019.

[ back ] 16. Björneborn 2017.

[ back ] 17. Carusi and Reimer 2010; Sabir and Engerer 2019

[ back ] 18. Assante et al. 2011.

[ back ] 19. Sarwar et al. 2010.

[ back ] 21. Schindler et al. 2012.

[ back ] 22. Popitsch and Haslhofer 2010.