I. Vico and La sapienza poetica

So Bacon already suggests two matters of chief interest to me: 1) that myth is an outgrowth of a primeval form of reasoning and 2) it is linked to a more bodily, sensate method of understanding. While he thus comes close to linking the meaning of fabulae to a common or popular wisdom, he never entirely gives up the notion of individual poetic genius that expresses itself in the tales, i.e. a wisdom that is deeper, subtler and recondite. The parable remains of use to the sciences chiefly for its ability to communicate to the human intellect whatever is abstruse and far removed from the common opinions of society.

Though I don’t want to stretch my comparison with Freud too much at this stage, it is worth citing in light of the above this comment he made to his alter ego, Wilhelm Fliess: “You taught me that a kernel of truth lurks behind every absurd popular belief” (Masson 1985:193).

II. Feuerbach’s Iliad of Wish-fulfillment

Feuerbach focuses on those moments when the gods appear directly in connection to a mortal’s mental state or open appeal, as in the first theophany in the Odyssey, when Telemachus is brooding over his father and Athena suddenly appears (i 113-118). Such moments show the real origin of religion in the projection of human emotions and desires; all other theophanies that are unmotivated by human necessities are merely poetic constructs ([1857] 1969:33). Thus Athena’s appearance to Achilles alone as he is about to draw his sword on Agamemnon (I 189-195) merely embodies his own understanding. Though the hero hesitates over what he is about to do, the point is that “Whoever hesitates in this way is already lord and master of his anger. On that account Athena only tells Achilles what his own understanding, his own sense of honor, indeed, his own advantage dictate” ([1857] 1969:35).

Homer is thus conscripted into Feuerbach’s muscular polemic as being completely compatible with the revolutionary, materialist ethos. The primary epiphany of his gods stands like a glaring truth in the eyes of the blind modern idealists, who insist that divinity is one of those sublime “objects of reason,” the fruit of rational speculation quite separate from sensuous experience. In reality, divinity is essentially just an object of desire, of wishing. It is something represented, thought, or believed only in that it is something desired, yearned for, wished for. “Just as light is only an object of desire for the eye because it is an essence corresponding to the essence of the eye, so is divinity only an object of desire overall because the nature of the gods corresponds to the nature of human wishes” ([1857] 1969:40-41).

III. Freud’s Odyssey of the Unconscious.

The dynamic of repression, then, preserves and even empowers childhood wishes, while at the same time banishing them. Hence the awesome power of these early wishes in the dream life, and, in a manner Freud would work out further in subsequent years, in the daydreaming and fantasizing that become art.

Childhood dreams are thus paradigm instances of the Urphänomen of dreaming, but they do not serve well to demonstrate the baroque operations of censorship that inform the adult dream work. Like Homer’s gods, they are self-evident scandals. This Freud demonstrates by relating a series of dreams culled from his own children, one of which shows us something of where the Homeric world stood in the fantasy life of Viennese children of the era: “My eldest boy, then eight years old, already had dreams of his phantasies coming true: he dreamt that he was driving in a chariot with Achilles and that Diomede was the charioteer. As may be guessed, he had been excited the day before by a book on the legends of Greece which had been given to his elder sister” (1900:129). We should note, then, that the very fact the Homeric texts were such an important part of a middle-class childhood (both in retold form and later in the originals studied at the Gymnasium) underscored their association with the “childhood of the human race.” Humanistic education in the nineteenth century seemingly recapitulated the development of Western civilization in a sense.

IV. Conclusion: Homeric Childhoods

Nietzsche had every right to be annoyed at the over-deployment of the childhood metaphor—and yet, it would continue to have a long career even after the writing of this letter in 1872, once the powerful idea of phylogenetic recapitulation became fashionable in post-Darwinian Europe and the United States. This metaphor has been one of the strands linking this paper together, and so I want now to work this further into my construal of the Homerizon, especially in reference to these particular projects of modernity and what they entail.

and idioms, as it were. All three authors assume that a degree of distance already exists between the genesis of the Homeric poems and some zero point of human development on the horizon. Thus while for the literate tradition of western culture “Homer” is the alpha point, “Homer” is also assumed to be the omega point for all previous pre-literate tradition(s) archived in the texts. The archival process—the process by which the poems come to be according to conventions, prejudices, and the mental and poetic limitations of the times—renders the text in some need of decoding. Yet there is still the hope that we can, through a new science of some kind, gain access to primal truths that are naively present in or through the text’s shimmering veil.

And they must have their food. Our childhood sits,

Our simple childhood, sits upon a throne

That hath more power than all the elements.

What is validated through invoking childhood desire in this way? In part, precisely those elements of imagination or fantasy that stand at variance with the limited agenda of rational hegemony and that are now re-authorized through reconciliation with Nature. We see this, for example, in Vico’s association of Homer with the violence and turbulence of the natural sublime. The violence of the heroic imagination is a direct consequence of its corporeal barbarity and relative proximity to bestial nature, yet this same violence is responsible for the sublimity—and superiority—of heroic poetry to any subsequent creations from the age of reason. But Vico does not side with textual effects over truth content. Though he contends that Homer’s texts contain corrupt and distorted histories from the most remote ages, Vico does not go to the Platonic extreme of dismissing the texts as mere falsifications aimed more at “aesthetic” pleasure than at what really is/was the case. Instead, Vico articulates a characteristic compromise position, saving a kind of truth for the Homeric texts that approaches a childhood epistemology.

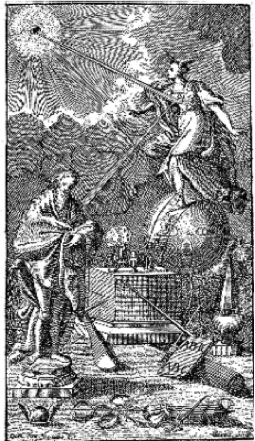

We might wonder how Vico remains optimistic about this self-made knowledge that is grounded in childish projection (as we would call it) and “robust ignorance.” But then we must recall that image from the frontispiece, which shows the light of Divine Providence bouncing off the figure of metaphysics and hitting Homer in the back. Humanity gropes its way toward a more perfect rationality and a fuller knowing because that is the ordained direction of history, a direction that is quite present in spite of the stumbling nature of human development (and its problematic circularity through ricorso). Hence this basic metaphysical optimism underwrites and empowers the imaginative and creative aspect of human activity, just as our own optimism for our children’s futures leads us to praise all their crude and self-referential creative efforts. The comparison is entirely Vico’s, who claims the ancients “gave the things they wondered at substantial being after their own ideas, just as children do, whom we see take inanimate things in their hands and play with them and talk to them as though they were living persons” (375). Great poetry, for all its disturbing imagery and even scandal, clearly has a civilizing mission in spite of its origins in self-referential ignorance and fear.

Poetic wisdom is thus a truly human wisdom; for all its faults, it speaks to the mind as it really is (or was) and fundamentally improves it (pace Plato!). In this way, Vico, though he seems eager to vindicate Divine Providence, constantly shores up the secular claims of human agency and underscores the internal validity of the historical process. This is precisely what makes him such a compelling figure of transition (or compromise?) between the dogmatically theological and the rabidly secular worldviews. What is at stake here in relation to Homer is just what human knowledge represents in the context of the threshing floor of history.

This transvaluation of the emotions follows quite strictly along the principles of his new philosophy, which teaches, “In feelings—indeed, in the feelings of daily occurrence—the deepest and highest truths are concealed” (Principles of the Philosophy of the Future 33 [{1843} 1986:53]). It is a philosophy that also puts sensuousness (Sinnlichkeit) and material reality to the fore as criteria of truth, against the abstractions of idealism. Small wonder, then, that the overtly material nature of the Greek gods attracts Feuerbach. Though figments of the imagination (something which in German thought was considered very positive, at least since Karl Moritz’s Götterlehre), the Greek gods represent at least a well grounded set of truly human wishes. The stark contrast between pagan Greek and Christian wishes in this regard is the substance of his peroration in The Essence of Religion.

Thus the basic, childish crudeness of the Greek religious imagination is what redeems Greek civilization from the perils and aridities of transcendent monotheism, which runs from the sensuous in full denial of its own humanity. Modernity must remember the Greeks in order to get back in touch with itself and with the real.

While it is true here that human desire is again being qualified as to its object, note that the thrust of Feuerbach’s philosophy suggests that human desire simply must take itself as its own object, in the light of the historical and material reality of its own needs. That is precisely the lesson of Homer’s gods, in all their human crudity and cruelty. Swimming quite consciously against the Platonic current, Feuerbach forges the Kallipolis of his “philosophy of the future” by following the tupoi of the poet, who stands nearer to the truth than the philosopher, since the truth as far as people are concerned is the living Mensch himself. [4]

While accepting many of these preconceptions, Freud’s new science comes to a very different conclusion about the unconscious intentions extracted from the ancestral tongue, and openly delights in the “unhallowed imputations” it makes at humanity’s expense. The brutalities it uncovers are not just phylogenetic, i.e. dating from the remote antiquity of the species, but ontogenetic as well, impinging on each and every childhood to this day. Childhood thus becomes the crossroads of both inherited and self-generated traumas.