Abstract

Introduction

The very first line of Homer’s Odyssey presents an interesting concept that is inherent in epic poetry and which Fitzgerald consciously includes in his translation: “Sing in me” the poet asks the Muse, and “through me tell the story” (1961). It is evident that this line describes a moment of inspiration during which the poet requests to be transformed into the medium the Muse will use in order to transmit her song. However, this sense of transcendence is not implied by other standard English translations of Homer.

The difference between these translations and Fitzgerald’s version lies in the way they communicate the role of the Muse. While all others portray her as an external factor that influences poetry, Fitzgerald instead describes a process of incorporation. In a sense, the poet needs to internalize the Muse in order to be able to sing; medium and message become one. “Sing through me” describes a live process—a performance, as the story unfolds through the poet’s song. However, since the development of writing and, subsequently, literature, the “oral” aspect of epic poetry has been hugely disregarded by scholars, and text has been placed at the center of attention. Ong writes:

Of course, while orality and textuality are considered two discrete modes of communication, we need to point that the former precedes the latter both from a chronological, as well as from a developmental perspective. Myths were circulating ancient Greece way before the arrival of writing. In addition, Ong (2012) mentions the Greeks’ fascination for the art of rhetoric, “the most comprehensive academic subject in all western culture for two thousand years”, that acted as “the paradigm of all discourse”, but again, in our case, “after the speech was delivered, nothing of it remained to work over.” (ibid). That is to say, there is no way we can study the oral practices of the past without using textual sources. All we are left with is the written record. Now, regardless of the two ends of a communication channel, the conventions of the medium itself can obscure the clarity of the message’s meaning. I clarify: what “mediates” between a sender and a receiver is what eventually affects the type of the message being sent, gives it new characteristics and influences a whole new way of thinking and acting. In McLuhan’s words, “The medium”, as an extension of ourselves, “is the message” (1964), therefore, choosing to examine a cultural activity through the lens of a particular medium over another will definitely bear epistemological consequences that will dictate the nature of our observations. How people receive the stories from the Epic Cycle will depend—among other things—on the medium that is transmitting these stories.

Video Games

Methodology

- the Telemachy (4 rhapsodies, from α to δ)

- the Phaeacis (4 rhapsodies, from ε to θ)

- the Apologoi (4 rhapsodies, from mid ι to μ)

- the Mnesterophonia (12 rhapsodies, from ν to ω)

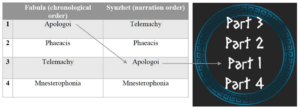

As the poem begins in medias res, I needed to consider the distinction between the Formalist fabula and syuzhet.

I wanted to use a first-person perspective as this could act as the player’s “virtual” point of view, reduce additional distractions and hopefully add to the overall immersion. Regarding the design of the levels, I decided each of them to be a small 3D spherical “planet”. The reasons for that are the following:

- The sphere is the 3D equivalent of the circle, and the latter has connotations of the “cyclic” manifestation of epic poetry (e.g. Epic Cycle, Sagas, etc.).

- The sphere has no entry points. It does not have a beginning or an end.

- The sphere promotes non-linearity and a sense of openness. Players are free to choose their own path.

As a result of the above, objects on the level are constantly visible and accessible. Players can get to know the events without reading the story the same way Homeric audiences might know the stories before they would request for a song.