Pentcheva, Bissera. 2024. “Mosaic and Mimesis: The Eikōn tou Theou and Models of Katanyxis in the Middle Byzantine Church.” In “Emotion and Performance in Late Antiquity and Byzantium,” ed. Niki Tsironi, special issue, Classics@ 24. https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HLNC.ESSAY:104135614.

Introduction

The image of Christ in the dome dominates and centers the program. The Anaphora (Eucharist Prayer) in the liturgy of Saint Basil defines the significance of this image. [3] Set at the apex, it visualizes the image of God––εἰκών τοῦ θεοῦ––the ideal form and model given to humanity but lost because of the sin of Adam. This icon calls the faithful to engage and try to recuperate this image in themselves and to imitate its example. The encounter encodes reciprocation: a performative act. Long before the establishment of the post-Iconoclast practice of placing of Christ’s figural icon in the cupola, the Byzantine liturgy trained the faithful in the mimesis of this εἰκών τοῦ θεοῦ even without material, visual stimuli. We recognize this practice in the liturgical poetry, more specifically in the kontakia and kanons which target the listeners’ imagination. For instance, Romanos Melodos’s (b. ca. late fifth century, d. ca. 550s) kontakion on the Second Coming speaks of the encounter with the face of Christ the Judge even through the contemporary sixth-century ecclesiastical interiors where this poetry was sang lacked the physical image of Christ. Romanos wrote: “All-Holy Savior of the world, as you appeared and raised up the nature / that was lying in offenses / as you are compassionate, appear invisibly to me (ἀοράτως ἐμφάνηθι) also, o Long-Suffering.” [4] In this stanza “appear[ing] invisibly” refers to imagined icon of God one conjures in one’s imagination as one confronts one’s past transgressions, repenting, and seeking forgiveness. The words trigger the reification of internal, ineffable icon: “When you come upon the earth, O God, in glory / and the whole universe trembles … then deliver me from unquenchable fire / and count me worthy to stand at your right hand.” [5] The faithful engage in a dialogue with this imagined image as they progress on their path to Salvation, uncovering, recognizing, and repenting for their past transgressions in order to re-form, recuperate the lost ideal form of the eikōn tou Theou. [6]

The Invisible Image and the Material Icon

The incarnation of Christ offers the possibility for an eventual return of the faithful to the image of God. Christ is the pure icon of God. He both shares in humanity’s form (“of the same form as us” συμμόρφους ἡμάς) and simultaneously imbues this form with divine glory (δόξα):

he [Christ] emptied himself, taking the form of a slave,

conforming himself to the lowliness of our body,

that he might conform us to the image of his glory. [13]

Christ takes on the human form in order to uplift humanity to the image of glory. He invests this form with doxa (glory). Salvation (σωτήρια, sōtēria) is thus understood as the restoration of humankind to its status before original sin and thus a return to being made in “the image of God” (εἰκὼν τοῦ θεοῦ) and deification (θέωσις, theōsis). In reciting St. Basil’s anaphora, the faithful are stimulated to conjure up this image of glory. But it is only after Iconoclasm that this internal vision acquires material, anthropomorphic concreteness in the physical icon of Christ in the dome.

Christ in the Dome after Byzantine Iconoclasm

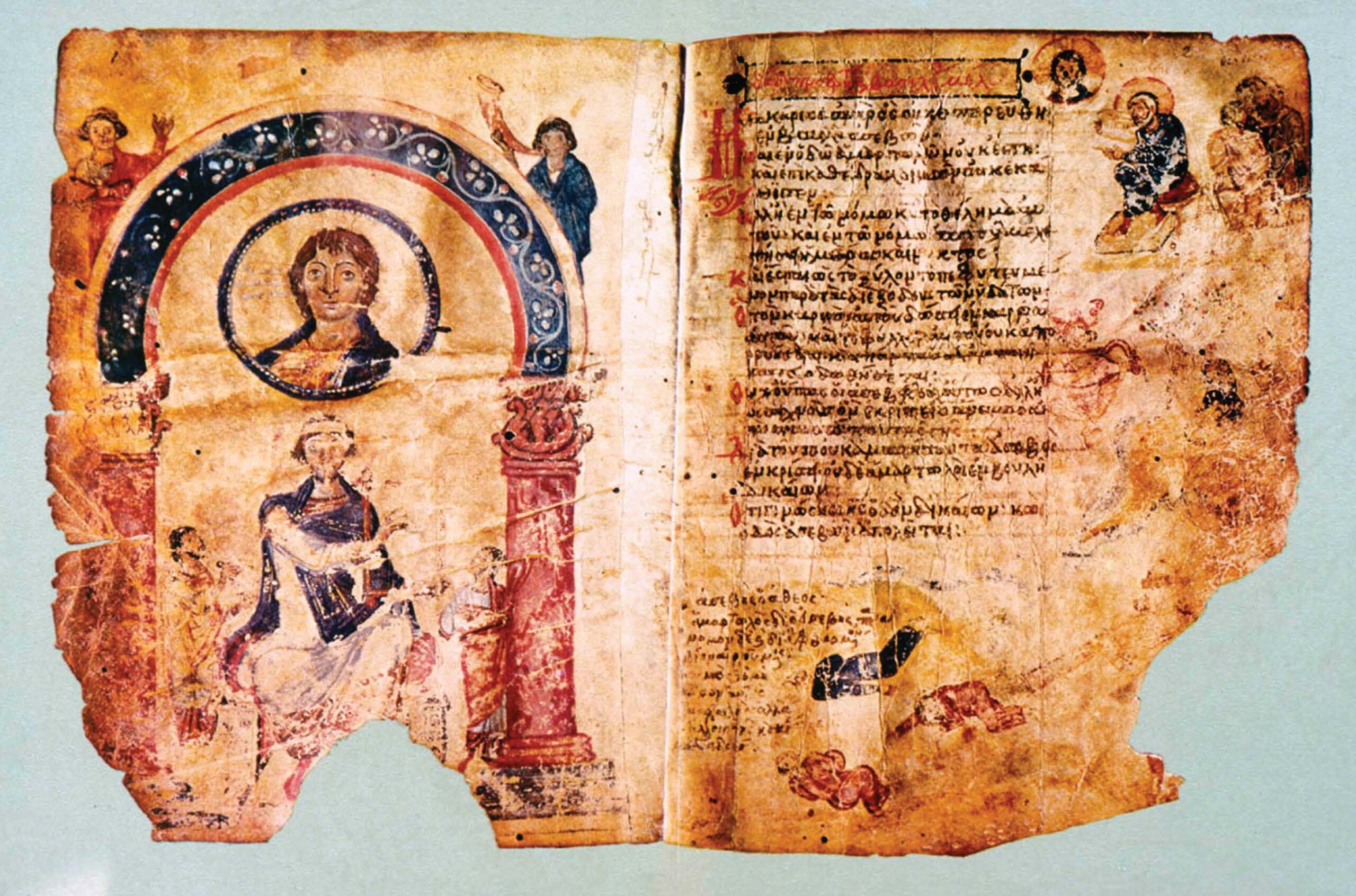

Byzantium develops a very idiosyncratic form of the eikōn tou Theou: an image of Christ set in a golden medallion. This particular shape became elucidated in the debates surrounding Byzantine Iconoclasm (726–843) and is likely anchored in the icon of Christ Chalkites that was set above the entrance gate of the imperial palace. The placement of the Chalkites celebrated the triumph of icon-worship in 843, and we see it in the preface miniature of the Khludov psalter (Figure 2). [14]

Soon after, the same round image came to occupy the apex of the main dome of Byzantine churches, reifying the belief that conversion, prayer, judgment, and salvation all issued from the light of God’s face. And this image became the stage on which the faithful were invited to practice their proleptic encounter with the Last Judgment scenario. [15]

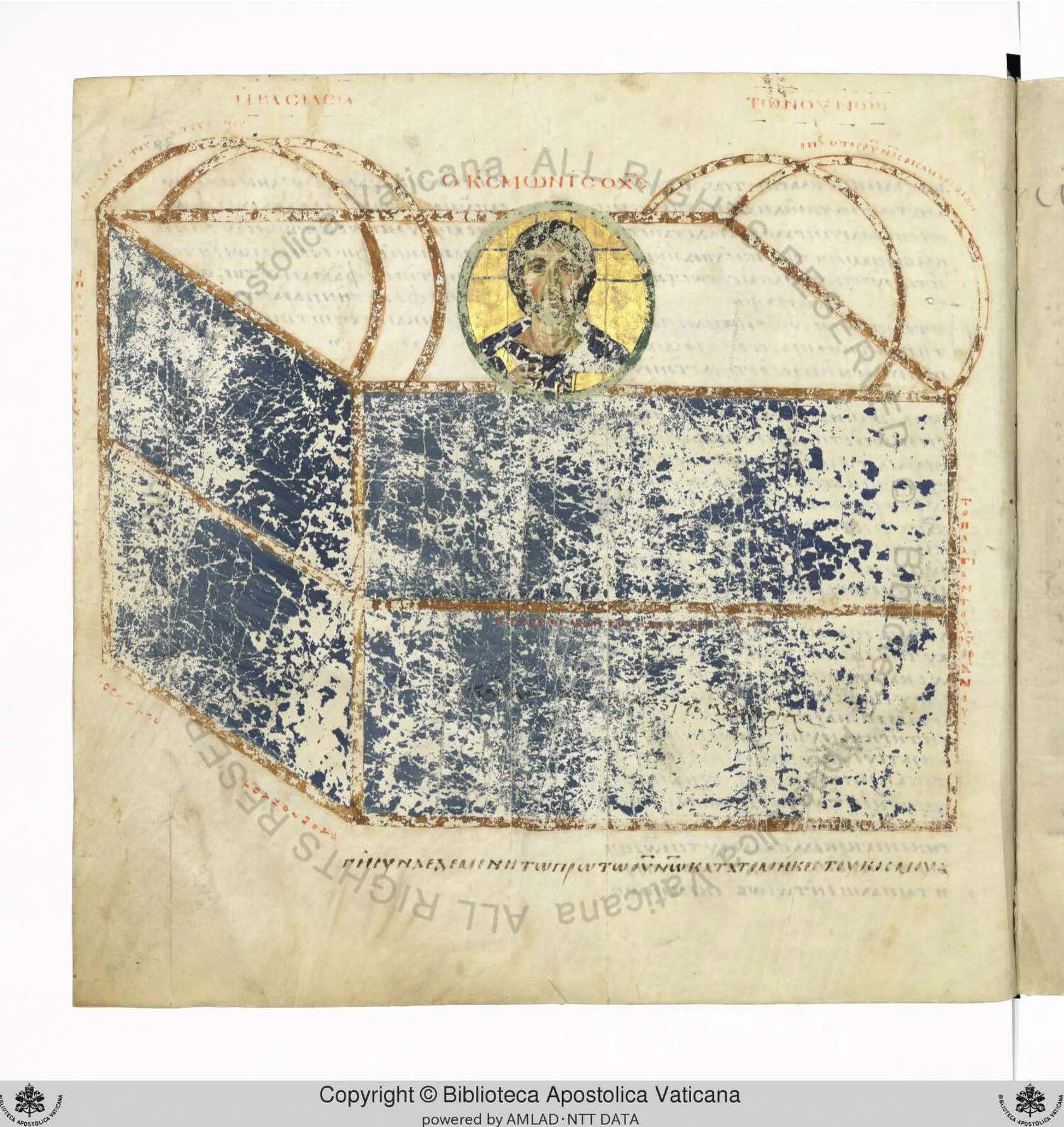

The medallion with the figural image of Christ takes over the sign of the cross (τύπος) enclosed in a circle. The aniconic sign was often stamped on the Eucharist bread that the worshippers consumed, and the same symbol graced the apex of the Justinianic dome in Hagia Sophia; today copies of this formula remain in the domical vaults of the Great Church (Figure 3). [16]

In the course of the iconoclast controversy, a complex discourse develops, which aims and succeeds at drawing an equivalence between the typos (sign) of the cross and the medallion icon of Christ. Theodore Stoudites (759–826), a monk and hegoumenos of the important Constantinopolitan monastery of the Stoudios, articulated the significance of this change when the medallion icon of Christ superseded the typos of the Cross:

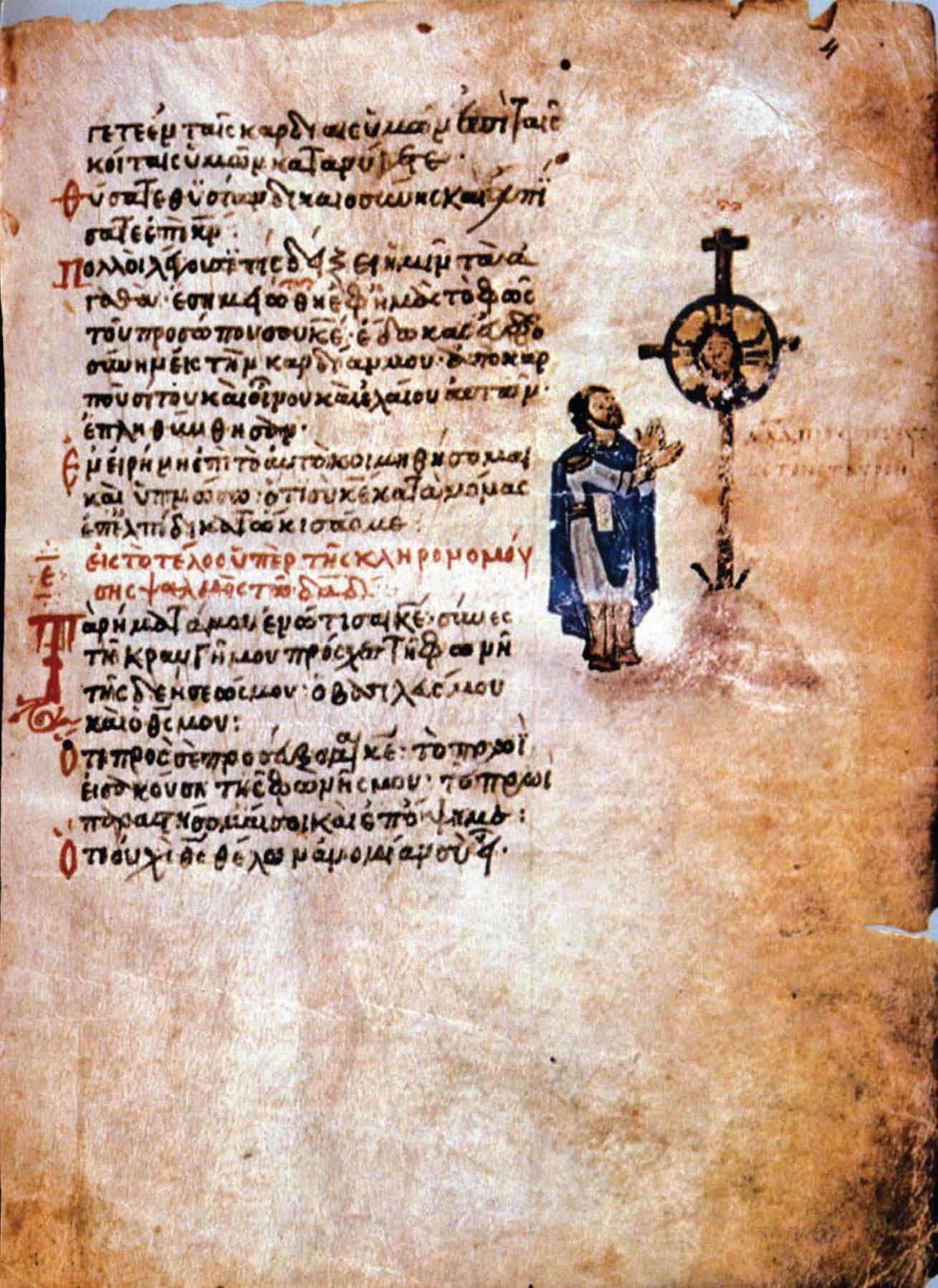

Theodore Stoudites recognizes that the copies of the Cross are legitimate images of the Cross because they transmit the shape without change. He then asks what is the difference between the typos of the cross and the icon of Christ? Since the icon transmits the features of Christ unadulterated and thus preserves the form, then it too performs according to the same principle that legitimizes the typos of the Cross. By drawing on the equivalence between typos and eikōn, Theodore secures the legitimacy of the figural icon. Ninth-century images push this argument a step further, making the eikōn visually supersede the typos of the Cross. The marginal psalters reveal this visual polemics with the miniature of David prophesying about the Cross on Golgotha (Figure 4).

Here a medallion icon is set at the center of the cross. The miniature illustrates the words of Ps. 4:7: “the Light of thy Face has been imprinted on us.” [18] All the faithful are imprinted with the Cross (in Baptism, in the Eucharist, through the blessing gesture), and this typos is now overlayered with the medallion icon of Christ: the light of Christ’s face.

The prominence of the round icon of Christ is attested in the Post-Iconoclast visualization of the cosmos in Kosmas’s Christian Cosmography. [19] The medallion eikōn tou Theou crowns the upper chamber of a space recalling an ecclesiastical interior. The icon in this upper realm marks the supracelestial domain (Figure 5).

The round icon of Christ further operates in scenes of conversion and prayer in the important Homilies of Gregory of Nazianzinos (Paris, BnF MS Gr. 510). The two miniatures reveal how the light of Christ’s face imprints itself on the faithful and transforms them. In the conversion of Saul/St. Paul (fol. 264v), Saul encounters the divine as he loses physical sight and at that moment metaphysical light streaming from the medallion icon of Christ touches and changes him forever from Saul to Paul (Figure 6).

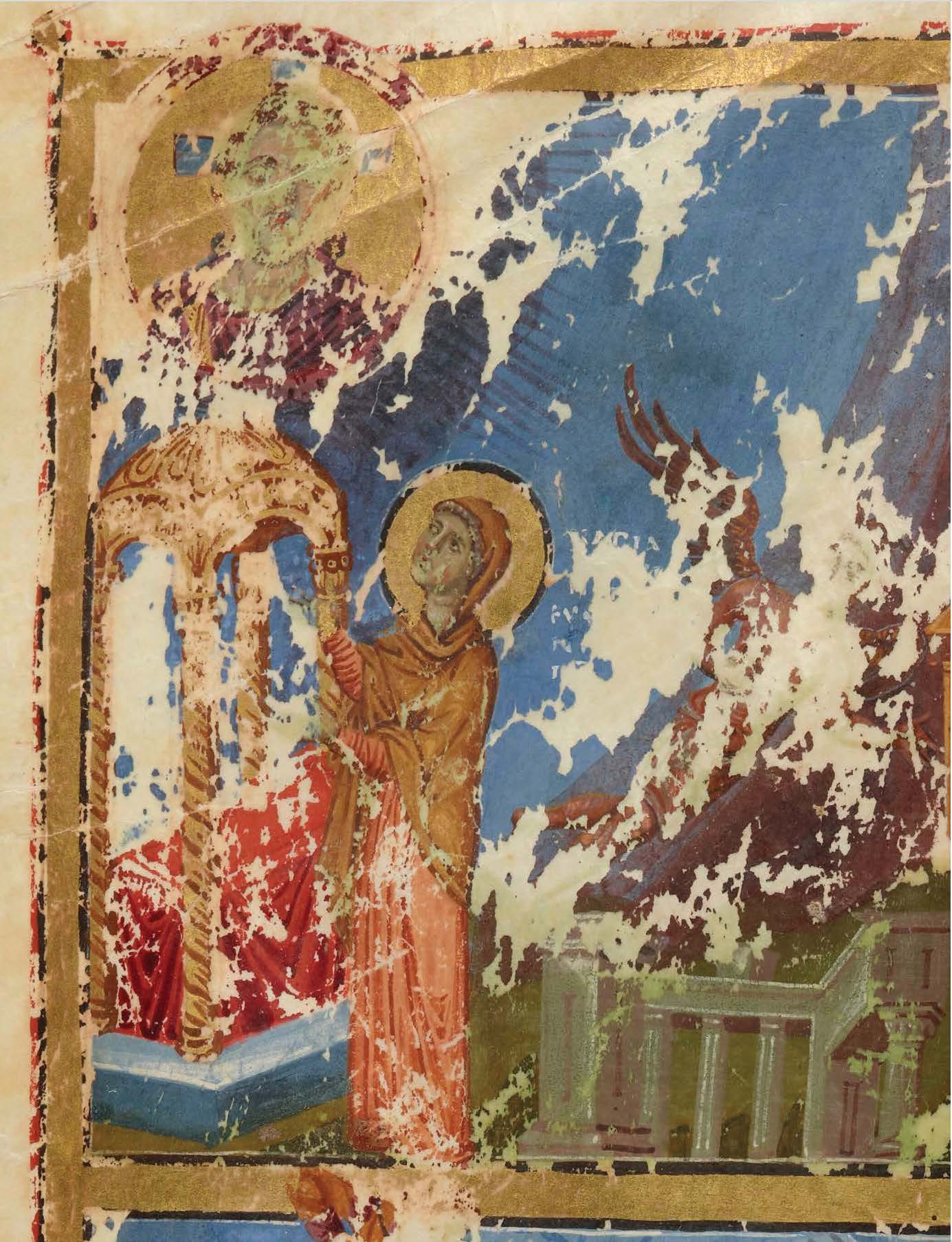

Similarly, the prophetess Hannah praying to the Lord (fol. 332v) is envisioned in the privileged position of receiving divine grace that flows from a medallion image of Christ (Figure 7).

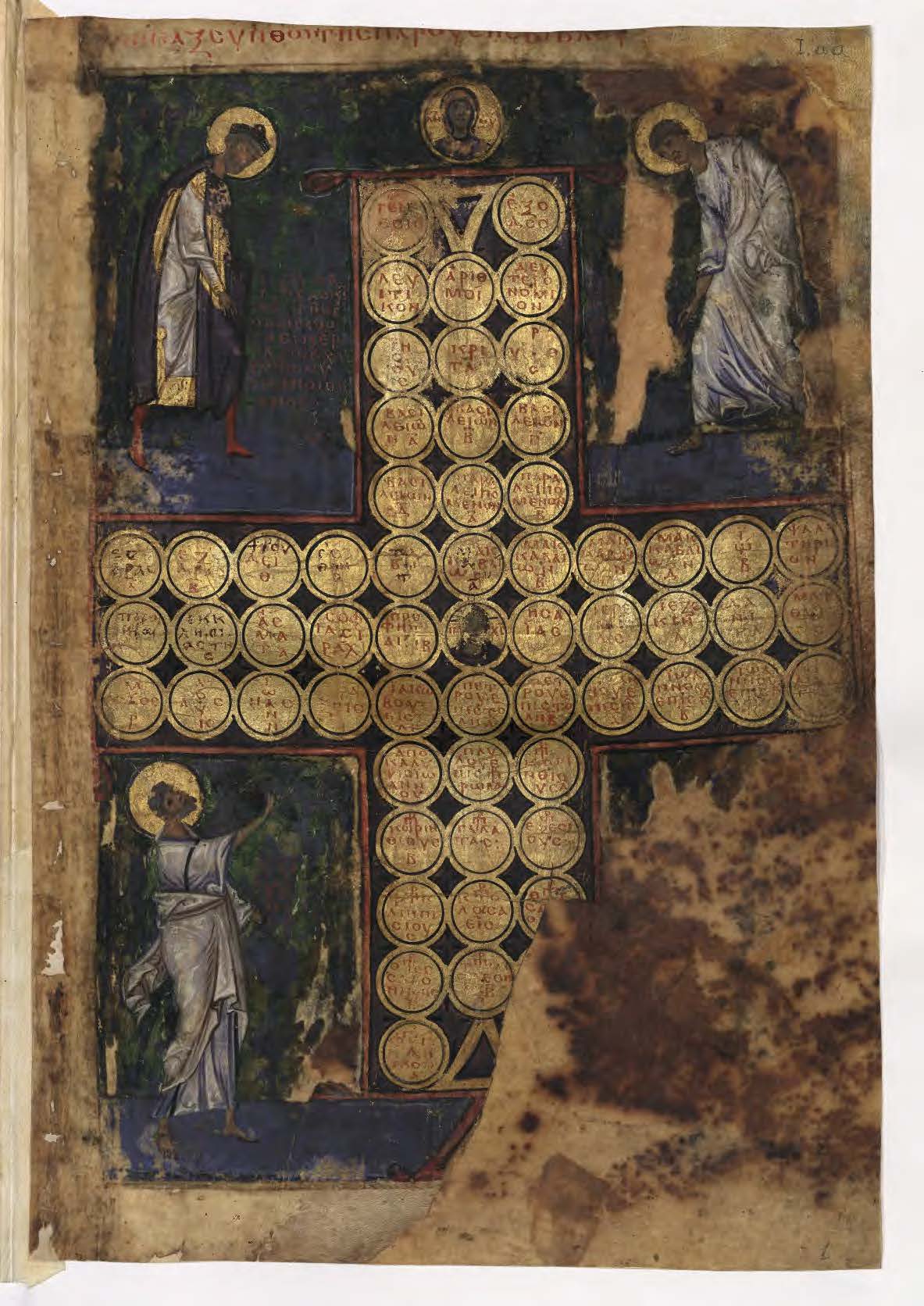

Beyond the world of miniatures, the medallion icon superseding the cross becomes a spatial reality in the post-Iconoclast interior of Byzantine churches. This connection is recognized in the miniature of the tenth-century bible of Leo the Sakellarios that depicts the infrastructure of all the books of the Bible as a cross formation of tiny medallions, which resembles the ground plan of a cross-shaped church. The roundel with Christ emerges in the center in the space evoking the dome, while the medallion with the image of the Virgin is set at the top, reminiscent of the apse (Figure 8). [20]

This visual structure of the miniature of the Leo Bible can be overlaid on the interior of Hosios Loukas (see Figure 1). And while the medallion icon of Christ nestles in the highest point of the naos, this is not the only encounter with the eikon tou Theou in the church. The same image confronts the faithful at the entry from the narthex to the nave, set above the door (Figure 9).

The Great Kanon, written by Andrew of Crete and performed on the Fifth Week of Lent, gives access to how the face of Christ was meant to be experienced in architectural interiors like Hosios Loukas. Through the open gates of the narthex, one sees the spacious interior and is drawn to this sudden raise in height of the ceiling. If the mosaics in the narthex of Hosios Loukas start from a cornice placed at 3.39 meters from the floor, in the naos they start at the height of 12 meters (Figures 10 and 14).

The eikōn tou Theou in tympanum above the gates marking the transition between narthex and naos guards the symbolic border between earth and paradise. We can hear echoes of this idea in the kanon of Andrew of Crete. [21] His words voice the desire of the faithful. As they approach the door of the narthex, seeking entry into the naos, they are attracted by light pouring from the dome into the naos. The faithful are reminded how this vision of promised paradise became a reality for the Good Thief (Figure 11).

Andrew of Crete writes: “A thief accused Thee, a thief confessed Thy Godhead: for both were hanging with Thee on the Cross. Open to me also, O Lord of many mercies, the door of Thy glorious kingdom, as once it was opened to Thy thief who acknowledged Thee with faith as God.” [22] The poetry voices the desire to emulate the model of the Good Thief and thus gain access to paradise. This drive to imitate is spelled out by the icon of Christ over the entry to the naos. And then the same image is repeated once more in the apex of the dome. Here it marks the end point of the journey.

Christ’s medallion icon in the cupola of the Byzantine church also mirrors another important encounter with the divine––the Eucharist chalice. The cup of the Patriarchs at the Treasury of San Marco offers one of the most articulate examples. The image of Christ is set in a medallion at the bottom of the chalice. The bowl inverts the great dome and becomes a transient container for the body of Christ. Once the cup’s Eucharistic content is consumed, the empty shell reveals the figural inscription of the Eucharist. The chalice functions as the microcosmic equivalent to the macrocosmos of the architectural dome (Figure 12). The pouring of the contents from the chalice could be seen in parallel to the cascading natural light from the cupola; the latter visualizes divine generosity, which offers the energy of life to the thirsty faithful.

Again, Andrew of Crete’s Great Kanon prepares the participant to perceive the architectural space in this way. He writes: “As a chalice, O my Savior, the Church has been granted Thy life-giving side, from which there flows down to us a two-fold stream of forgiveness and knowledge, representing the two covenants, the Old and the New.” [23] The entry into the church is envisioned as a fusion with the divine icon, structured on the model of the Eucharist. But the figural decoration after Iconoclasm makes this encounter more direct and this visual clarity and material directness is powerfully manifested in Hosios Loukas. The images of Christ set at the entry and at climactic apex of the dome uplift the faithful to the divine and recall the Eucharist chalice with its salvific outpour (Figures 9, 10, and 11).

Distance: Katanyxis and the Pantepoptēs

The image of Christ in the dome transforms the nave (the kallichoros) into a personified space of judgment (see Figure 1). The medallion image of Christ in the apex triggers compunction and sonically articulates the descent of divine mercy and forgiveness. [28] Christ in the dome opens a stage for the rehearsal of the future Judgment as a proleptic scenario. A modern viewer cannot immediately grasp the drama of this interpellation. Yet, the fear and trepidation it can excite in the faithful can be recuperated by the medieval inscriptions framing the eikōn tou Theou in the dome. The verses inscribed around the image of Christ in the cupola in twelfth-century church at Trikomo in Cyprus reveal the intended approach to the divine Judge (Figure 13): “He who sees all from the distant place sees all those who enter here. He examines their souls and the movements of their hearts. Mortals, tremble (with fear) before the Judge [at Judgment!].” [29]

The inscription states that nothing escapes the gaze of Christ; he observes all who enter and reads their hearts and the movement of their souls. The indictive voice abruptly switches to the imperative, warning the viewer to approach the Judge “with trembling and fear.” A second text further secures the futurity of the scene as that of End of Time: “And let all the angels of God worship him” (Hebrews 1:6). [30] The composition sets the stage that is only completed with the viewer, who becomes the accused standing before the judge. The visual and spatial composition makes all the visitors practicing the Byzantine liturgy to feel englobed inside the divine eye and liable for all their actions during their life on earth.

The image of Christ in the dome of the nave can stir katanyxis, but this complex feeling of fear and trembling can be coupled with the relief stemming from the possibility for divine forgiveness. At Hosios Loukas, a Crucifixion scene is depicted in the tympanum to the left of the main door leading from the narthex to the nave. This image shows the moment in which water and blood concretize as an efflux flowing out to save humanity. With the slight curve of Christ’s body, the Crucifixion visualizes the concept of divine condescension, συνκατάβασις; the Son bends down from his high celestial position to the lowliness of the human race in order to save the faithful (Figures 14 and 15).

Mary’s words in the Great Kanon (Ninth Ode) of Andrew of Crete affirm the power of this divine condescension: “Christ became a child and shared in my flesh, and performed willingly all that belongs to my nature, only without sin. He set before thee, my soul, an example and image of His condescension.” [34] The two prefixes, syn– (“with”) and kata-(“down”) in the Greek word for condescension (synkatabasis) express both Christ’s descent and His willingness to bend down and partake in human nature and suffer death at the Crucifixion in order to raise it up through His Resurrection (Figure 16).

Christ bending is linked to the outpour of his blood. It flows from the wounds in his hands, side, and feet. The blood forms clean, thin streams. It inspires penance and aims to trigger a reciprocal flow of tears in the faithful. Andrew of Crete’s Great Kanon expresses these ideas channeling the address of the repentant sinner:

By the outpour of His blood, Christ washed the sin away. And by the giving up of His Spirit, he lifted humanity to the divine. The words speak of divine descent and closeness. Similarly, the choice of place for the Crucifixion mosaic gives visual concreteness to synkatabasis. The Crucifixion set in the narthex is physically closer to the viewer (as mentioned earlier the mosaics in the narthex start at 3.39m height in the narthex as opposed to 12m in the nave).

Nearness: The Mosaics in the Narthex and the View from Below

Christ in the kontakion on Peter by Romanos Melodos further assures his disciple about the future salvation with a powerful metaphor:

giving you my hand as before [reference to Christ’s rescuing Peter in the sea]

because, having taken in it a reed as a pen, I am starting to write a pardon for all Adam’s descendants.

My flesh, which you see, becomes for me like paper,

and my blood like ink where I dip my pen and write,

as I distribute an unending gift to those who cry:

‘Hasten, Holy One, save your flock’. [41]

Christ bends, he who weaves the clouds, bows to touch mortal feet in order to give a chance of the faithful to live in Him. He sacrifices His own body, making it into the book, writing Salvation with his own blood. The viewer in the narthex of Hosios Loukas is thus asked to move between the two scenes the Washing of the Feet and the Crucifixion, envisioning the progress of Salvation. And on the walls of the katholikon, these two images are also set in close in proximity.

Furthermore, the mosaic of the Washing of the Feet faces the Doubting Thomas in the southern niche (Figure 17). The latter too visualizes the overcoming of distance and the enjoining with the divine.

Thomas’s doubt in Greek δίσταγμα (distagma from the verb διστάζω [distazō], ‘to doubt, to hesitate’) plays on sonic similarity with διάστασις (diastasis), ‘separation’. By choosing not to believe, he separates himself from his fellow disciples, who rejoiced in seeing the resurrected Christ. Thomas thus cuts himself off from their happiness and from the possibility to partake in the Savior. He only overcomes this diastasis in the moment he plunges his finger in the wound of Christ. Through the knowledge gained by touch, Thomas can disperse his distagma/doubt. With this regained intimacy with the Savior, he becomes reintegrated in the community of the faithful. Romanos’s kontakion on the Doubting Thomas is saturated with sensuality of this touch. [42] As he plunges his finger in the wound, Thomas whispers to Christ:

Satisfy me, who am yours. You were patient with strangers;

Be patient too with your own and show me your wounds,

that, like springs, I may draw from them and drink. [43]

Thomas burns in desire to touch and to satisfy a deeply seated need (Figure 18).

His faith speaks through the language of the lover who wants to embrace and penetrate the beloved. [44] Later on, Thomas states in the same kontakion, stanza 16: “The side which I grasp, I enjoy.” Pleasure and full satisfaction drips from this tactile encounter. And the sensual pleasure in the body of Christ also expresses the notion of the pliability of the divine, descending, bending down, giving in, captured in the Greek word of συγκατάβασις. Just like the bending Christ washing the feet of the apostles across the narthex, so too the Master offering his body to the desirous touch of the apostle is manifestation of supreme condescension. This reversal or extreme lowering of the divine propels the magnitude of the Salvation purchased through this contrasting act of willing descent.

In the narthex of Hosios Loukas, the two scenes of the Washing of the Feet and the Doubting Thomas are in a continual dialogue. And just like in the Washing of the feet, Christ speaks metaphorically that his body is the parchment on which the stylus/Cross writes Salvation, so too Thomas’s finger becomes a stylus in the kontakion of Romanos Melodos:

writing for believers the place from where faith springs up.

From there, the thief drank and came to his senses again.

From there, the disciples watered their hearts.

From there, Thomas drew the knowledge of the things he sought.

First he drinks, then gives to drink. [46]

Placing the finger in the wound becomes an act of writing Salvation of streams of life-giving water given to the faithful to drink. If the Washing of the Feet strengthens the allusions to the bread/body, the scene of the Doubting Thomas paradoxically liquifies Christ’s flesh into a stream of salvific nectar, offered to the faithful. Furthermore, the visual appearance of the material surface of the mosaic enhances this sense of liquefaction (Figure 17). The rays of light in the chrysography of the garment and on the surface of the closed doors become visual metaphors of the pouring of light. Divine doxa/glory is seen in the rays of sunlight offering metaphorical life-giving water.

Bibliography

Footnotes

ἐστιν αὐτοκίνητος καὶ ἑτεροκίνητος. Ὅταν ἡ ψυχὴ, καὶ ὑμῶν μὴ σπευσάντων, μηδὲ ἐπιτηδευσάν-

των δακρυώδης καὶ κάθυγρος καὶ ἠπία γένηται,

δράμωμεν, ὁ γὰρ Κύριος ἀκλήτως ἐλήλυθε· σπόγγον

ἡμῖν διδοὺς λύπης θεοφιλοῦς, καὶ ὕδωρ ἀναψύξεως (55)

δακρύων θεοσεβῶν πρὸς τὴν ἐξάλειψιν τῶν ἐν τῷ

(808) χάρτῃ πταισμάτων, φύλαξον ταύτην ὡς κόρην ὀφθαλ-

μοῦ ἄχρις οὗ ὑποχωρήσῃ· πολλὴ γὰρ ἡ ἰσχὺς τού-

του, ὑπὲρ τὴν τοῦ ἐξ ἡμετέρας σπουδῆς καὶ ἐπινοίας

προσγινομένου· οὐχ ὅτε βούλεται ὁ πενθῶν,

οὗτος κάλλος πέφθακε πένθους· Trevisan 1941:264–265.

[ back ] 35. Τὸ σῶμα κατεῤῥυπώθην, τὸ πνεῦμα κατεσπιλώθην, ὅλος ἠλκώθην, ἀλλ᾽ ὡς ἰατρός Χριστέ ἀμφότερα, δία μετανοίας μοι θεράπευσον, ἀπόλυσον, κάθαρον, πλῦνον· δεῖξον, Σωτήρ μου, χιόνος καθαρώτερον.

Τὸ Σῶμα σου τὸ Αἷμα σταυρούμενος ὑπὲρ πάντων ἔθηκας, Λόγε· τὸ μὲν σῶμα, ἵνα ἀναπλάςῃς με, τὸ αἶμα, ἵνα ἀποπλύνῃς με· τὸ πνεῦμα παρέδωκας, ἵνα ἐμὲ προσάξῃς, Χριστὲ, τῷ σῷ Γεννήτορι, Triodion katanyktikon:472–473, English trans. Kallistos Ware 1994:392.