Trahoulia, Nicolette S. 2025. “Performance and Subjectivity in an Illustrated Psalter: Vatican gr. 1927.” In “Emotion and Performance in Late Antiquity and Byzantium,” ed. Niki Tsironi, special issue, Classics@ 24. https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HLNC.ESSAY:104135619.

The Vatican psalter gr. 1927 has received little attention since 1941 when Ernst De Wald published the manuscript’s miniatures. The manuscript was definitely intended to be an impressive production, with miniatures painted on gold ground, and an emphasis on blue, red, and purple pigments. It is heavily illustrated with 145 miniatures, and originally must have had more if we take into account that a number of folios are missing. The manuscript measures 245 by 185 mm, large enough for folios to comfortably accommodate both text and illustration, but also quite portable. Lacking a colophon, the manuscript can be dated on the basis of the style of the miniatures to the late eleventh or early twelfth century. [5] Illustrations are, as a rule, placed at the head of each psalm, within the text column. One defining feature of this manuscript is the extensive use of excerpts from the psalter text written either within the illustration or alongside it in the margin. This proximity of word to image means the experience of viewing the images is closely aligned with the reading or recitation of the psalter text. I would also suggest it indicates an especially scholarly environment for production. Rather than reproducing a substantial portion of the psalter text, as is the case in Vatican gr. 1927, miniatures in other illustrated psalters tend to include short inscriptions that simply label figures or events. [6] Whether Vatican gr. 1927 was intended for monastic or lay use remains open. Nevertheless, any manuscript with illustrations must have been made for a special audience.

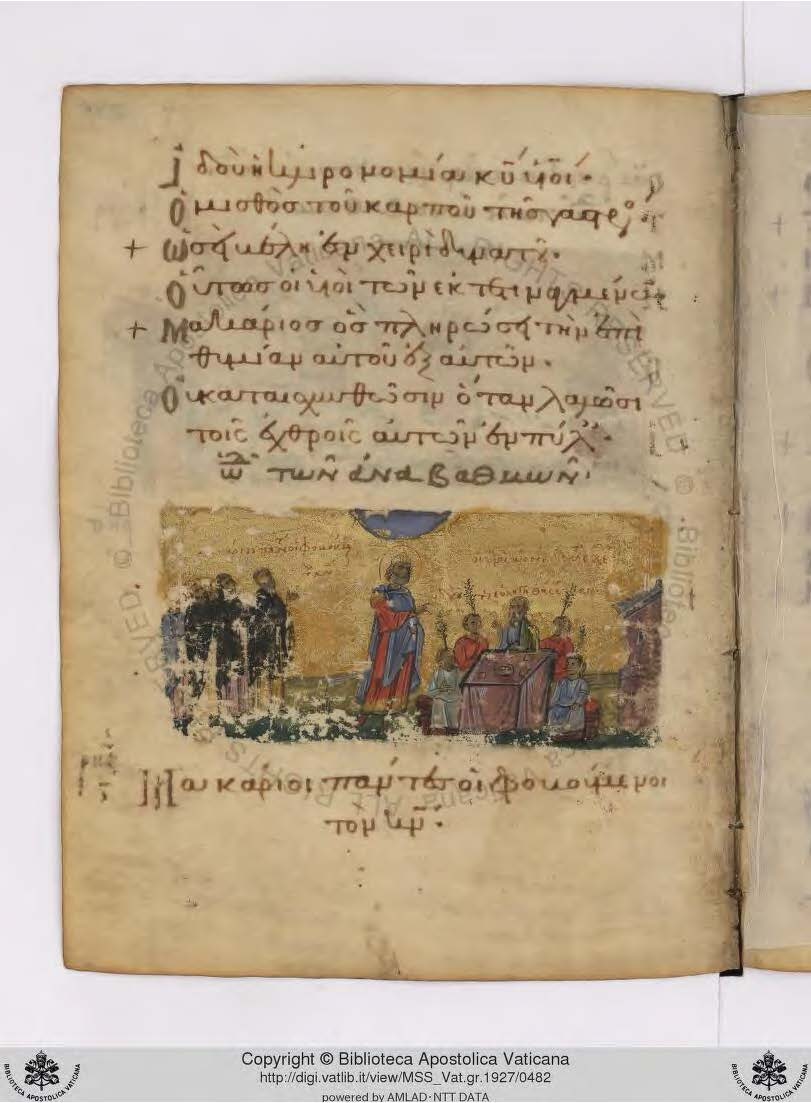

Scholars who study psalter illustrations have labeled Vat. gr. 1927’s mode of illustration as predominantly “literal,” to describe the manner in which the miniatures directly illustrate the words of the psalms. A particularly apt example of this mode of illustration can be seen on folio 238 verso in the miniature for Psalm 127 (128) (Figure 1). On the left, monks raise their arms in prayer, while on the right, the blessed man sits at a table with children who have olive branches protruding from their heads, illustrating verse 3 of the psalm, which describes the children of the blessed man as being like olive plants. David stands in the center of the illustration and gestures towards the figures seated around the table. In general, there can be said to be three different strategies when illustrating psalters: David can be shown to participate in narrative scenes; narrative or other types of illustration can be used that do not contain David; or David can be presented as the narrator. Vatican gr. 1927 chooses the third mode far more often than any other illustrated psalter. In addition to the so-called “literal” illustrations, scattered throughout the manuscript are scenes from the life of David, as well as other subjects drawn from the Old Testament. It is notable that there are relatively few illustrations that contain New Testament subjects. [7] While the latter feature means the typological relationship between Christ and David is not emphasized in this manuscript, we will nevertheless see that, compositionally, the relationship of David to Christ is a major part of the illustrations. Indeed, as already noted, the most salient feature of Vatican gr. 1927’s miniatures is the role that David plays in the images.

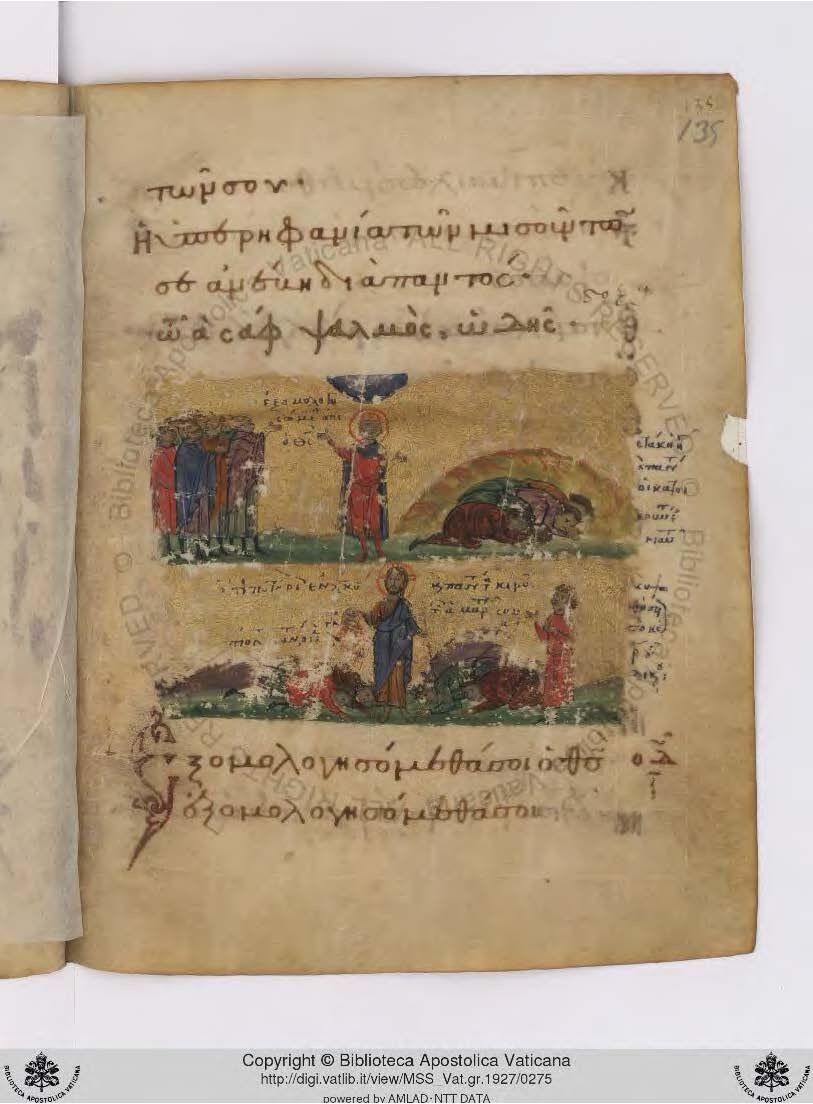

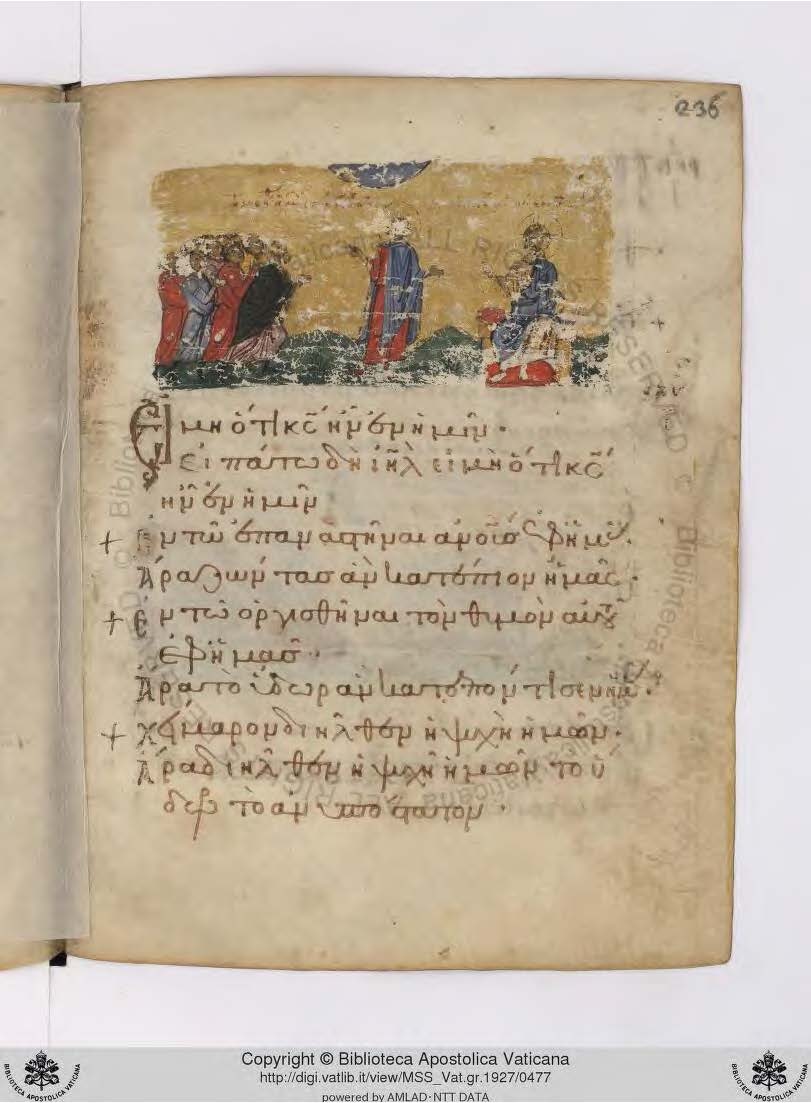

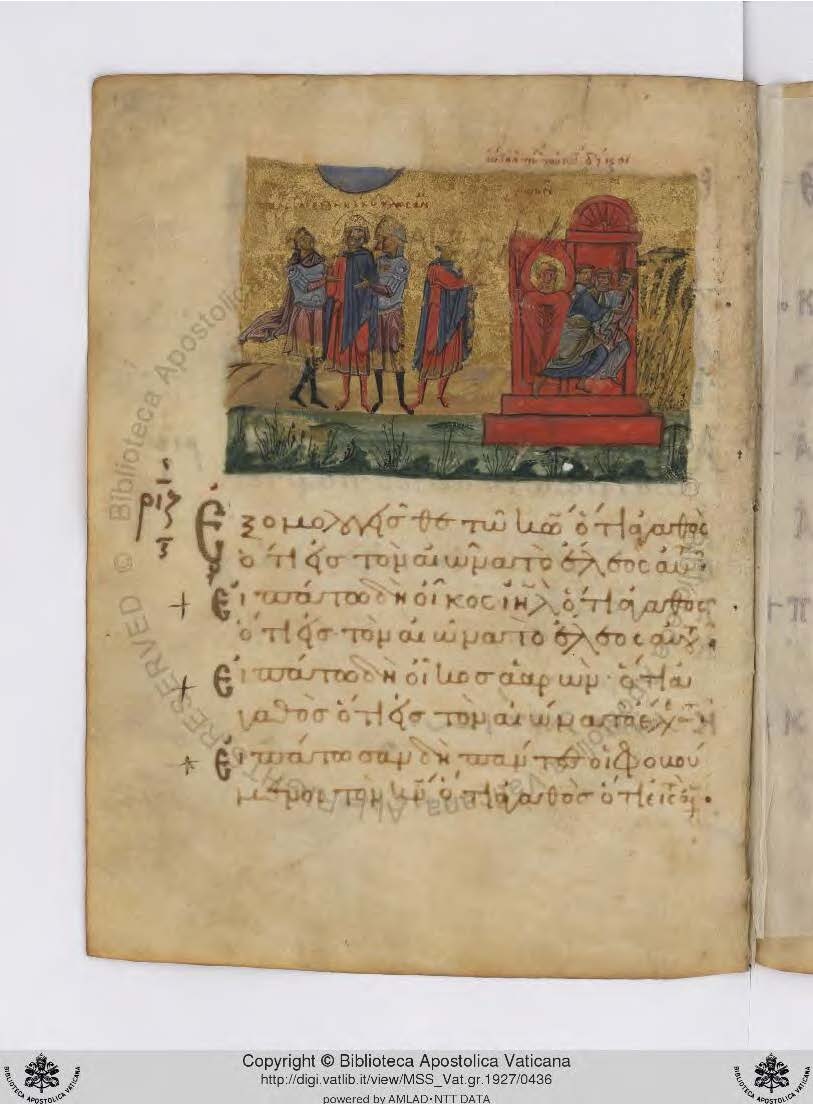

Within the miniatures, David is often placed on an axis with Christ in Heaven. And frontality is almost always reserved for Christ and David. We see this in the miniature on folio 135 recto where, in the upper zone of the miniature for Psalm 74, David stands between a group of men who raise their hands to heaven, while on the other side a group prostrate before fire (Figure 2). Below this scene Christ stands between two groups who prostrate before him. The visual relationship that is posited between David and Christ throughout the manuscript effectively presents David as intermediary between Christ and humankind. In an illustration on folio 236 recto, a frontally posed David stands between Christ enthroned and a group of worshippers, gesturing simultaneously to the figures on either side of him (Figure 3). The inscription, taken from Psalm 123 (124), indicates the importance of having the Lord on one’s side.

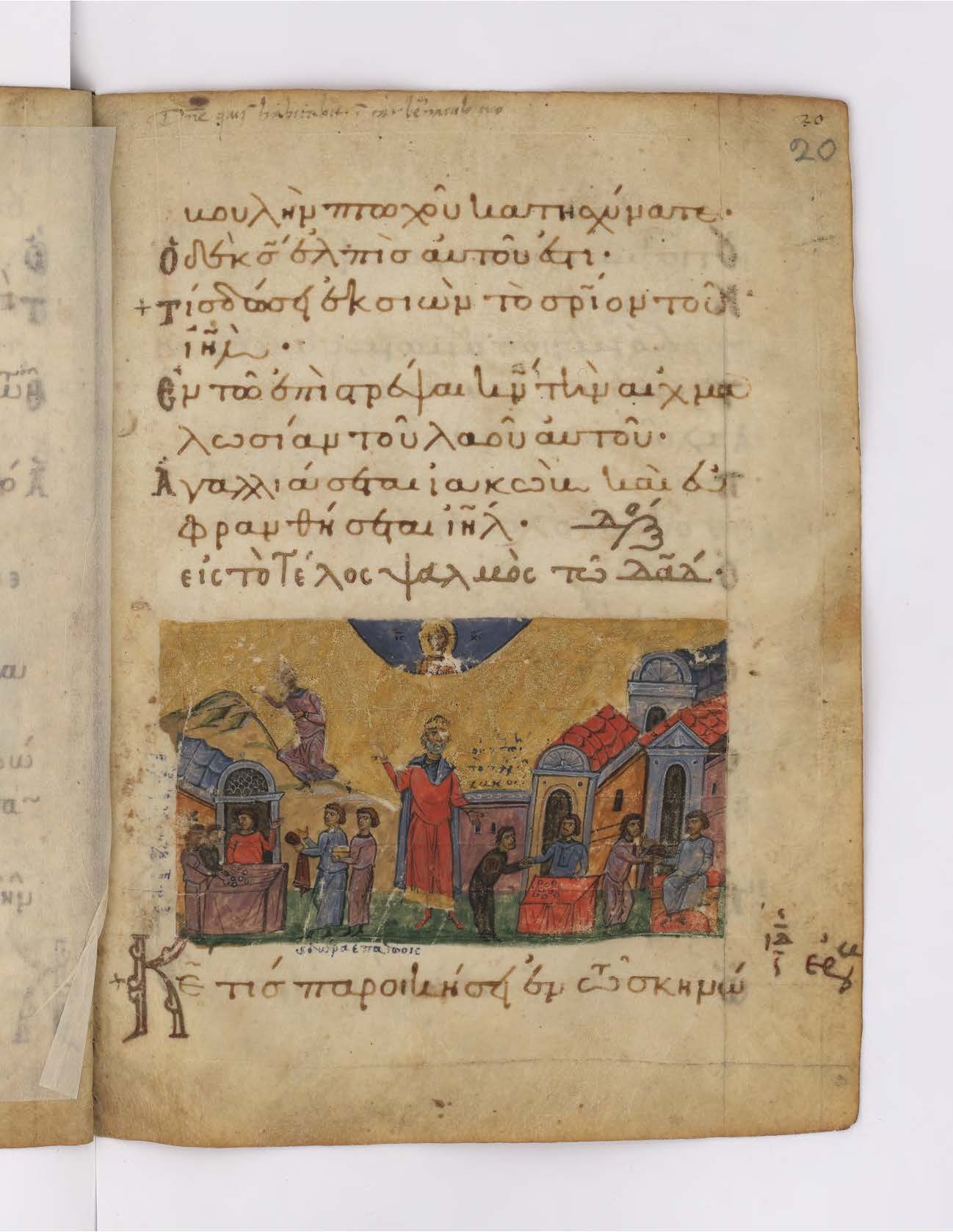

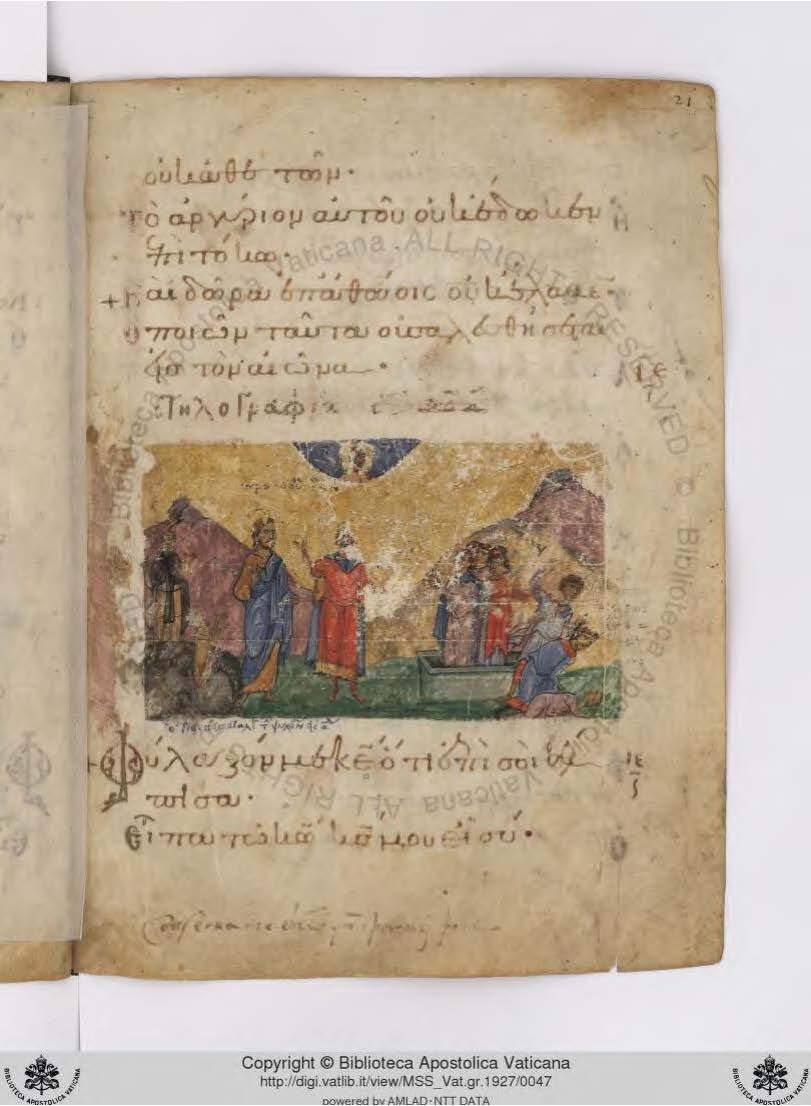

The consistent visual motif of a frontally posed David in the center of an illustration, so that he directly addresses the viewer via gaze and gesture, is what sets this psalter apart from other illustrated psalters. The figure of David is also often larger than the other figures in the illustration, making him seem to straddle the viewer/reader’s space and the pictorial space. This is apparent on folio 20 recto, where David stands under a bust of Christ within the arc of heaven (Figure 4). He points to the upper left to the man who, in the words of Psalm 14 (15), ascends the holy hill, while below on either side of David, figures handle coins on tables as examples of those who either succumb to usury (on the right) or refrain from engaging in this sinful behavior (on the left).

As we see with these examples, some miniatures are quite complex, containing a variety of actions that relate to different verses of a psalm. In these illustrations, David serves as a visual anchor, indicating that he is the teller of these stories and that it is his voice which is here animated. On folio 21 recto David stands next to Christ, who also appears in an arc of heaven above (Figure 5). The different groups of figures on either side of Christ and David refer to a different verse from the psalm. The figures standing in a sarcophagus to the right must illustrate verse 10 of Psalm 15 (16) which refers to those whom the Lord does not allow to undergo decay, while further right two figures are being executed, possibly a reference to those whose sorrows are multiplied because they worship another god (verse 4). The standing Christ turns slightly toward David, while also directing his gaze toward the Old Testament king, effectively illustrating verse 8 which speaks of receiving the Lord’s counsel. Significantly, Christ holds a scroll, an indication of the wise counsel he passes on to David. A pit with a naked figure opens at Christ’s feet, while a monk stands to the left. These elements can be interpreted as referring to verse 10 which mentions the soul in hell. David stands in the center of this complex miniature and, unlike Christ and the other figures, does not appear to take part in the narrative action of the scene, but rather faces the viewer and gestures to right and left. His direct address of the viewer/reader via gesture and frontal pose is that of an orator recounting the psalm verses. The fact that Christ appears twice, both as a frontal bust in heaven and as an active figure within the scene, alerts us to how these miniatures are conceived overall. Christ in the arc of heaven above can be said to be an extradiegetic figure, while the figure of Christ who turns to David and hands him a scroll is an intradiegetic figure. Although the psalms are not narrative texts, this terminology is appropriate to the miniatures which do stage a series of actions. In certain cases, the actions depicted are connected to stories, such as events from the life of David, while in other cases the actions give visual form to the ideas and themes contained in the lyrical psalm verses. David, like Christ, is both an intradiegetic and extradiegetic figure, and more often the latter.