Tomić, Marka. 2025. “Performativity of Old Testament Verses: Proverbs (9:1-6) in the Liturgy and Church Decoration in the Late Medieval Balkans.” In “Emotion and Performance in Late Antiquity and Byzantium,” ed. Niki Tsironi, special issue, Classics@ 24. https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HLNC.ESSAY:104135618.

Wisdom has built her house;

she has set up its seven pillars.

She has prepared her meat and mixed her wine;

she has also set her table.

She has sent out her servants, and she calls

from the highest point of the city,

“Let all who are simple come to my house!”

To those who have no sense she says,

“Come, eat my food

and drink the wine I have mixed.

Leave your simple ways and you will live;

walk in the way of insight”

1. Introduction

2. Book of Proverbs (9:1–6): liturgical ritual and visual forms of representations

The content of Proverbs (9:1–5) performed at the liturgy also took a visual form of representation in monumental painting. In line with different liturgical contexts, the first verse from Solomon’s Book of Proverbs accompanies the figure of this Old Testament king and prophet within several thematic ensembles, some of which are an integral part of monumental church decoration in Medieval Balkans. It is often written on a scroll in the hand of Solomon, who is invariably depicted among the prophets in the domes of Byzantine and Serbian churches churches (Mother of God Peribleptos in Ohrid, 1294/1295, Figure 1; Mother of God Hodegetria at the Patriarchate of Peć, between 1335 and 1337, Figure 2; Markov Manastir, 1376/1377; Ravanica, ca. 1385). [5] Regarding the prophet cycles of the Palaiologan era, it bears emphasizing that the selection of Old Testament figures and prophetic messages was based on the liturgical practices and theological intricacies of this period. The text on Solomon’s scroll belongs to the quotations from Old Testament stories that explain the meaning and mystery of Christ’s incarnation.

In addition, his image with a scroll quoting verse 9:1 is often found in the festal scene of the Annunciation (Mileševa, between 1220 and 1227; Sopoćani, ca. 1365, Figure 3; St. Achilleos in Arilje, 1296; Markov Manastir, Figure 4 and 5). [6]

The historicity of Christ’s incarnation is indicated through the joint representation of David and Solomon—both kings of Judah, prophets, and forebears of the Lord. [7] A deeper conceptual connection with the Annunciation is suggested by the texts on their scrolls (Solomon, Prov. 9:1; David, Ps. 44,11), which begin to appear from the tenth century onward and become far more frequent later. [8]

In the next stage of Byzantine liturgy, in parallel with the Christological one, the Eucharistic interpretation of Proverbs (9:1–6) emerged, which sees the Old Testament allegory about the feast of Holy Wisdom as the prefiguration of the institution of the Eucharist, the most important ritual foundation of the earthly church. The enriching of the liturgy of the Great Church of Constantinople with the poetic hymnody of Palestinian monastic rites, among them poetic pieces of Holy Thursday, is assumed to have been an important process in the history of the liturgy, which started in the ninth century and was only completed in the twelfth. [9] The iconographic response to this liturgical overtone, however, did not appear before the late thirteenth century and the Palaiologan era that brought the expansion of painted programs and a more elaborate arsenal of Old Testament symbolic images. Particularly distinctive for its thematic and iconographic characteristics is the composition Wisdom has built her house, whose iconographic form was directly inspired by the verses in Proverbs (9:1–6). [10] The theme of personified Divine Wisdom inviting people to accompany her to a Feast appeared in Byzantine art in the late thirteenth century (Mother of God Peribleptos in Ohrid, 1294 /1295), (Figure 6) [11] and further developed in the Serbian artistic milieu (Gračanica,ca. 1320, Figure 7; [12] katholikon of Hilandar Monastery, 1321, restored 1804; [13] Dečani Monastery, Church of Christ Pantokrator, ca. 1343 [14] , Figure 8), with some examples also found in Russia (Dormition Church in Volotovo near Novgorod, 1363) [15] and Georgia (Zarzma, middle of the fourteenth century). [16]

This group of paintings shares the same visual articulation of the Old Testament poetic image—Holy Wisdom sitting at a table, in some cases in the form of a three-headed figure as the personification of the three hypostases of the Holy Trinity, surrounded by servants in front of the Temple of Seven Pillars.

Unique in its extensiveness and narrativity is the Holy Wisdom theme at Dečani, which unfolds in four episodes. [17] The last two are particularly notable: they illustrate the fifth verse, “Come, eat my food and drink the wine I have mixedˮ and show angels giving people communion with bread and wine. [18]

However, two further examples that can be added to this brief survey are particularly noteworthy—the Transfiguration parekklesion in Hrelja’s Tower of the Rila Monastery (1334/1335), (Figure 9a, 9b) [19] and Markov Manastir near Skopje (1376/1377), (Figure 10), [20] where the abstract theological thought on Holy Wisdom, inspired by Proverbs 9:1–6, was given not only a considerably different but also a much more complex iconographic elaboration in comparison with the other examples. Moving away from the literal illustration of Old Testament verses, painters and commissioners of the frescoes in Rila and later in the Church of St. Demetrios in Markov Manastir designed an original ensemble that draws on the poetic hymnody of Holy Thursday and theological treatises. These two painted programs should be seen as the ultimate examples of the very close ties between liturgy and symbolical-metaphorical imagery.

3. The Feast of Holy Wisdom in Hrelja’s Tower at the Rila Monastery (1334/1335) and in Markov Manastir (1376/1377)

In 1334/1335, one of the most prominent nobles under the Serbian king Dušan, protosebastos Hrelja, built and frescoed a tower (pyrgos) at the Monastery of St. John of Rila, the cultic center of this important Balkan hermit and saint, which had become part of the Serbian state after the Battle of Velbuzhd (1330). [21] Above the naos of the Transfiguration parekklesion on the upper story of the tower, in a blind dome, there is the Old Testament allegory about the feast of Holy Wisdom (Figure 9). At the center of the composition is Holy Wisdom on a rainbow in a mandorla surrounded by seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit in the form of seven semi-nude winged figures, and in the register below the Table of Wisdom approached by groups of bishops (Figure 11) and martyrs on one side and apostles and Old Testament kings on the other. In the last group, Solomon stands out in imperial ornate, pointing to Holy Wisdom in glory above him with one hand and holding a scroll with a quote from Proverbs (9:1) in the other (Figure 12). The remaining verses (9:3–5) are written on three scrolls arranged on the north, south and east side of the composition’s lower segment. [22]

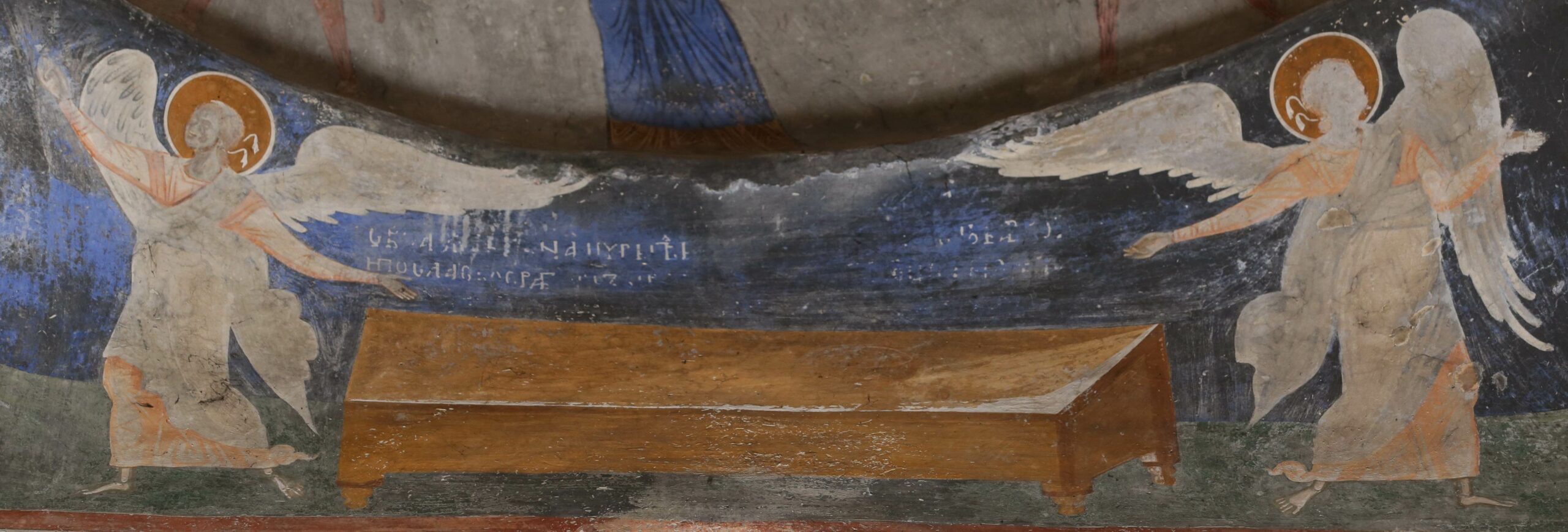

More than four decades later, another relevant fresco was painted above the narthex of the Church of St. Demetrios at Markov Manastir, an endowment of the Serbian kings Vukašin and Marko Mrnjavčević (1376/1377). [23] The blind dome and upper walls of the narthex display a complex composition whose programmatic focus is on Christ as the embodiment of the Wisdom of the Word of God (Η ΕΝΥΠΟСΤΑΤΟС ΤƔ Θ(ΕΟ)Υ / ‹ΛΟΓΟΥ СΟΦΙΑ›), (Figures 10 and 13). God the Son in glory is shown seated on a red rainbow arc and blessing with both hands. Christ’s youthful image originally was surrounded with yet another, lozenge-shaped mandorla. His star-studded aureole is carried by seven winged figures personifying the seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit (Is. 11:2), defined by inscriptions as: the Spirit of Knowledge, the Spirit of Counsel, the Spirit of Fortitude, the Spirit of Piety, the Spirit of Wisdom, the Spirit of Understanding, and the Spirit of the Fear of the Lord (Figure 14). Quite expectedly, the iconographic emphasis is on the symbolism of the Temple of Wisdom, and so an eighth figure, instead of a personification of the Spirit of the Lord, represents the Old Testament prophet and king Solomon with a scroll inscribed with a quotation from the first verse of the ninth chapter of the Book of Proverbs (Figure 15). Between the personifications of the Gifts of the Holy Spirit and King Solomon are eight six-winged seraphim shown in profile. They are stepping forward with their arms extended prayerfully towards the figure before them. The third segment of the composition, arranged around the ring enclosing the personifications of the Gifts, the seraphim, and Solomon, contains, on the east side, a table approached by the righteous grouped into nine choirs (the Old Testament prophets, male and female martyrs, nuns and ancestors, and, on the south side, the apostles, bishops, monks, and deacons) (Figure 16). An angel clad in a chiton and himation stands at either end of the table, pointing to the bread and wine on the table with one hand and inviting the saints with the other. The images of the chalice with wine and the paten with bread on the table used to be more visible, and so was the fragmentarily preserved inscription with a quotation from the Book of Proverbs (9:1–5, Figure 17). The fourth, and last, segment of the composition occupies the upper register of the walls. Below the choirs of the righteous and the table of Holy Wisdom, there are on the east and west walls sixteen figures of martyrs approaching the immortal table from the north and south sides in processions of four. Based on the surviving inscriptions, the figures on the west wall are known to represent: Thyrsos, Leukios, Philemon and Apollonius (south group) (Figure 18); and on the east wall, Manuel, Sabel, and Ismael (north group). If we take common origin as a clue to the identity of the fourth martyr in the latter group, then he may be St. James the Persian. An example is provided by Dečani, where the four martyrs are portrayed together. The group of martyrs on the north side of the west wall is difficult to identify without inscriptions and specific iconographic traits, and the question of their identity remains open. By contrast, four youths with short curly hair and caps on their heads on the south side are easy to identify as three Jewish boys, Ananias, Azarias, and Misael, and the prophet Daniel. [24]

The compositions in Hrelja’s Tower at the Rila Monastery and in Markov Manastir have their closest parallels in the later examples of Holy Wisdom with the personifications of the Gifts of Holy Spirit, those in the katholikons of Morača (after 1617) [30] and Nikolje (1697). [31] While on the whole both examples of the Old Testament allegory of Wisdom employ the same iconographic strategy and language, subtle differences between Rila and Markov Manastir can be detected. While the older iconographic solution of the personified Divine Wisdom was retained at Rila, in Markov Manastir, the image and the accompanying inscription emphasize the representation of Christ as the embodiment of the Wisdom of the Word of God. Further, it is important to note that, at Rila and Markov Manastir, the seven pillars of Solomon’s temple, shown in the group of Wisdom has built her house images as painted architecture, acquired the form of personified Gifts of the Holy Spirit, albeit based on different formal models. This iconographic transformation of the theme of Wisdom’s Feast reveals a deeper conceptual link with Isaiah’s prophecy about the eight Gifts of the Holy Spirit that rest on the tree of Jesse (Is. 11:1–2). [32] However, the content of this text would not keep its original form in later interpretations. Let us recall the influential view of John Chrysostom, who—drawing on the prophet’s quote (Is. 11:1–2)—speaks of the seven pillars of Solomon’s temple that represent the seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit. [33] Besides theological texts, the symbolism of the temple of Wisdom would also become dominant in iconography, which, as we have seen, began to deviate from the basic literary source. [34] Nonetheless, it should be noted that, in the iconographic structure of the composition in Markov Manastir, Solomon’s figure, as the replacement of the Spirit of the Lord, is grouped in the segment of the composition with the personifications of the Gifts of the Holy Spirit, while in Rila it belongs to the thematic group of the righteous—the Old Testament kings. The direct link with the prophetic verses (Is. 11:1–2), however, survived in the later period, as evidenced by the Feast of Holy Wisdom in Morača, where the composition includes the figure of the prophet Isaiah with the above-mentioned quote. [35] Finally, the Feast of Holy Wisdom in Markov Manastir has richer thematic contents than the older example. The group of sixteen martyrs approaching the immortal table in processions, their hands raised in supplication—the iconographic mark of the apostles approaching to receive Holy Communion—additionally underlines the Eucharistic symbolism of the image.

4. The reception of the Byzantine Patristic tradition in medieval Serbia

5. Book of Proverbs (9:1–6) and Byzantine hymnography

Kosmas of Maiuma’s Canon for Holy Thursday, chanted at that day’s liturgy, contains clear references to Proverbs 9 aimed at giving visual form to the meaning of the Last Supper. The first troparion of the first ode of the canon already paraphrases the opening verses of Proverbs 9:

The second troparion of the first ode reads:

while Kosmas’s verses in the third troparion call:

The second part of the compositions at Rila and Markov Manastir, showing saints who approach the immortal table, is again based on the Canon for Holy Thursday, more specifically, the irmos of the ninth ode:

Adopting familiar iconographic patterns, as explained above, painters faithfully showed the ascended Lord on the heavenly throne and the table of immortality approached by saints. The Table of Wisdom, in particular, was seen in a complex web of meanings, since it existed as a separate literary and visual motif in medieval Serbia, and its connotation, besides the Eucharistic sense, could also refer to the spiritual table, i.e. the Gifts of the Holy Spirit. [65] The Eucharistic meaning in which the liturgy mentions Christ as Wisdom and Logos is suggested by another hymnographic text chanted on Easter Sunday: John Damascene’s Paschal Canon (Canon for Easter Day) sung toward the end of Basil’s and Chrysostom’s liturgy. [66] The second troparion of the ninth ode reads:

This, then, suggests that the theme of Christ the Wisdom was inspired by the verses of Proverbs 9 in their original form and in poetic hymnody. In some cases, more frequently in later ones, this is additionally clarified through representations of the hymnographers Kosmas of Maiuma and John Damascene. [68] This is hardly surprising, in view of the fact that, over the course of its history, especially in the Palaiologan period, Orthodox medieval art drew theological ideas from the liturgy—the Eucharistic rite and those rites connected with the cycle of the church year. [69]