Crostini, Barbara. 2024. “Performing the Bible at Dura: A Panel of Elijah and the Widow of Sarepta as tableau vivant.” In “Performance and Performativity in Late Antiquity and Byzantium,” ed. Niki Tsironi, special issue, Classics@ 24. https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HLNC.ESSAY:104135601.

Abstract

Durene images as tableaux vivants

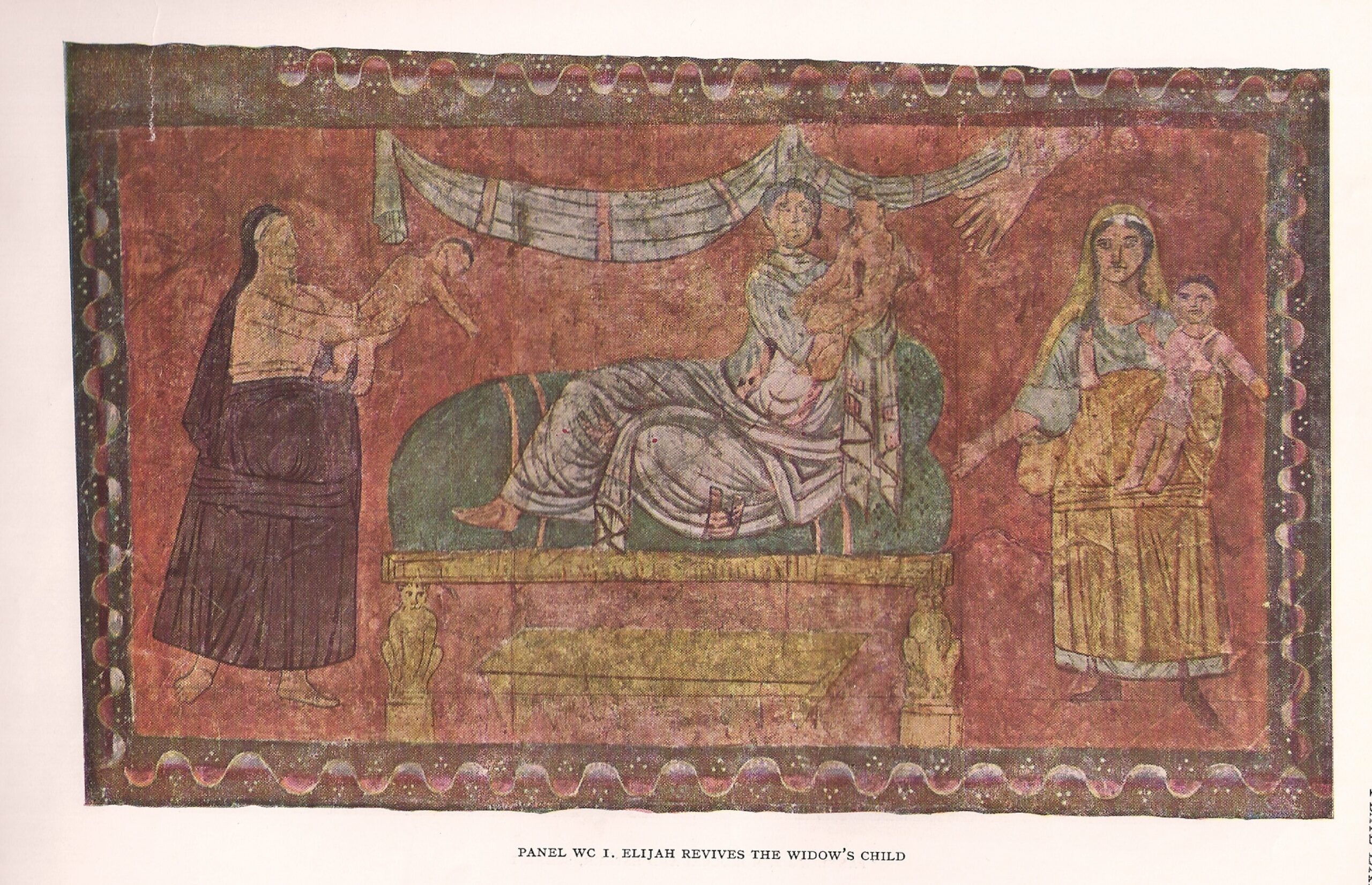

In its more recent revival, the art of tableaux vivants has been considered a “very intellectual amusement” that plays with the ambiguity between living and not living, between being still and moving, being silent yet gesturing implied utterings. [3] The panel painting of the resurrection of the son of the widow of Sarepta by the prophet Elijah is both thematically and formally consonant with such a definition (Figure 1). The episode dramatizes the threshold between life and death, revealing its porous consistency through Elijah’s power, negotiated through his God. Aesthetically, the composition foregrounds dialogue between the characters, implying the audience’s knowledge of the intended spoken words. It is a speaking image, evoking, in synthetic form, the staging of the episode and its emotional drama.

Concepts embodied in performance

Within the cycle of panels, its position on the West Wall confers prominence to the representation. Nonetheless, this panel has so far received only scant attention in scholarship. I propose that the artist was inspired by the actual staging of this episode and that its impact on the viewers depends on their approach to it as a performative act, rather than as a narrative text. Moreover, the iconography chosen presupposed a viewer’s cultural horizon that encompassed acquaintance with the rhetoric of Greek tragedy in order to fully decode the message encapsulated by the image. Engaging with such aspects beyond the written biblical text enriches our understanding of the dynamics of the compositional scheme, both from the point of view of the original composition, and from that of its reception through activities conducted within the synagogue space. The latter, then, can be properly considered a place for wider outreach that likely included both visual art and different types of live performance as key strategies of communication. Embodied performance could reach a wider audience and its visuality cut across linguistic barriers to effectively deliver its message of hope. In Lieber’s definition:

The compositional scheme of the panel

Representational dynamics

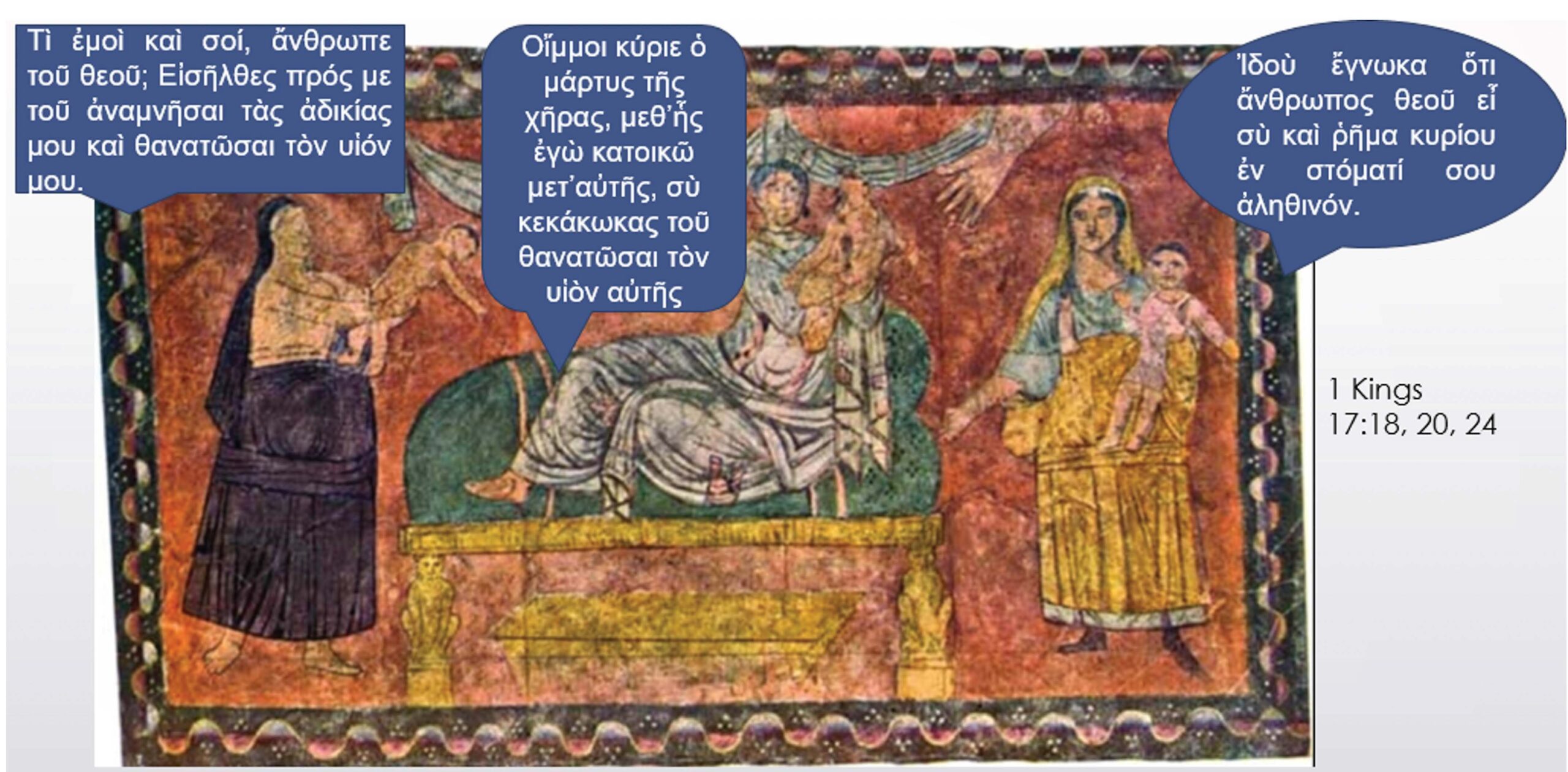

There is no doubt that the artist’s distillation of the narrative is highly effective. The choice of actors, their gestures and poses, create a tableau vivant. Rather than demand of this representation a literal rendition of each phase of the biblical text, itself in fact often elliptical, one may read the sequence as pointedly highlighting the words spoken by each character. In place of providing detailed figuration for their actions, the tableau singles out the speech-acts as conveying the essence of the story and, with it, the message intended for the viewers. This can be visualised precisely by adding speech bubbles to the image (Figure 3).

The mourning widow with the dead son

The prophet in the upper room

The widow proclaims the resurrection of her son

Greek tragedy and biblical narrative

A relation between Greek tragedy and biblical narrative has been occasionally noted. Parallel occurrences of tragic events, such as the blinding of Zedekiah and that of Oedipus, have been analysed. [29] The overwhelming presence of dialogue in biblical narrative—and even silence—alerted scholars to another aspect of its theatrical dimension. As Kenneth Craig wrote for 1 Samuel:

Craig may be speaking figuratively, but his choice of words is significant. In his view, this narrative choice—much like a theatrical staging—opens multiple possibilities of interaction “between narrator and characters, narrator and readers, and readers and characters.” [31] Because of such complexity, the Bible offers particularly rich possibilities of involvement. As Craig concludes, “[i]t is this process of reconstructing the story’s perspectival parts into a coherent whole that makes the Bible such exciting reading and marks one of its artistic claims to notice.” [32]

Elijah as Alcestis

Dialogue as a mark of performance

The invention of imaginary dialogues based on biblical storylines demonstrates a multi-faceted engagement with the mechanisms of interpretation. Such practice was particularly lively in the Syrian church and specifically included pieces on Elijah and the widow of Sarepta. One exchange after the death of the widow’s son renders the woman’s accusations to the prophet even more explicit than those reported by the biblical text. “Give me back my only child […] for he was slain because of you!”, she says, to which Elijah answers: “Never has anyone been killed by me, and here you are calling me a murderer. Do you suppose that I am God, to be able to revive your only son?” [40] In this version, Elijah’s prayer to God is impassioned but more self-concerned. In the solitude of his upper room, the prophet explicitly asks God all the questions we would like to see answered:

this widow who has received me?

Why did you send me to her,

why did you bring her son forth from her womb? Lord, I call upon you with feeling,

I beg of your mercy;

listen, Lord, to the prayers of your servant

and return the soul of this boy.” [41]

At this point the hand of God speaks, as it were, and the deal is signed: God will release the soul of the child when Elijah lets go of the key to the heaven, allowing rain to fall again. The conclusion of this memre does not attribute more direct speech to the woman, but only describes her as rejoicing and giving praise to God. While this poetic version contains a narrative frame, however minimal and reduced to “stage directions,” another Syriac fragment offers pure dialogue. [42] One might envisage these pieces acted out in different voices, as the performance of later kontakia by Romanos the Melod are now imagined. [43]

Stage Props

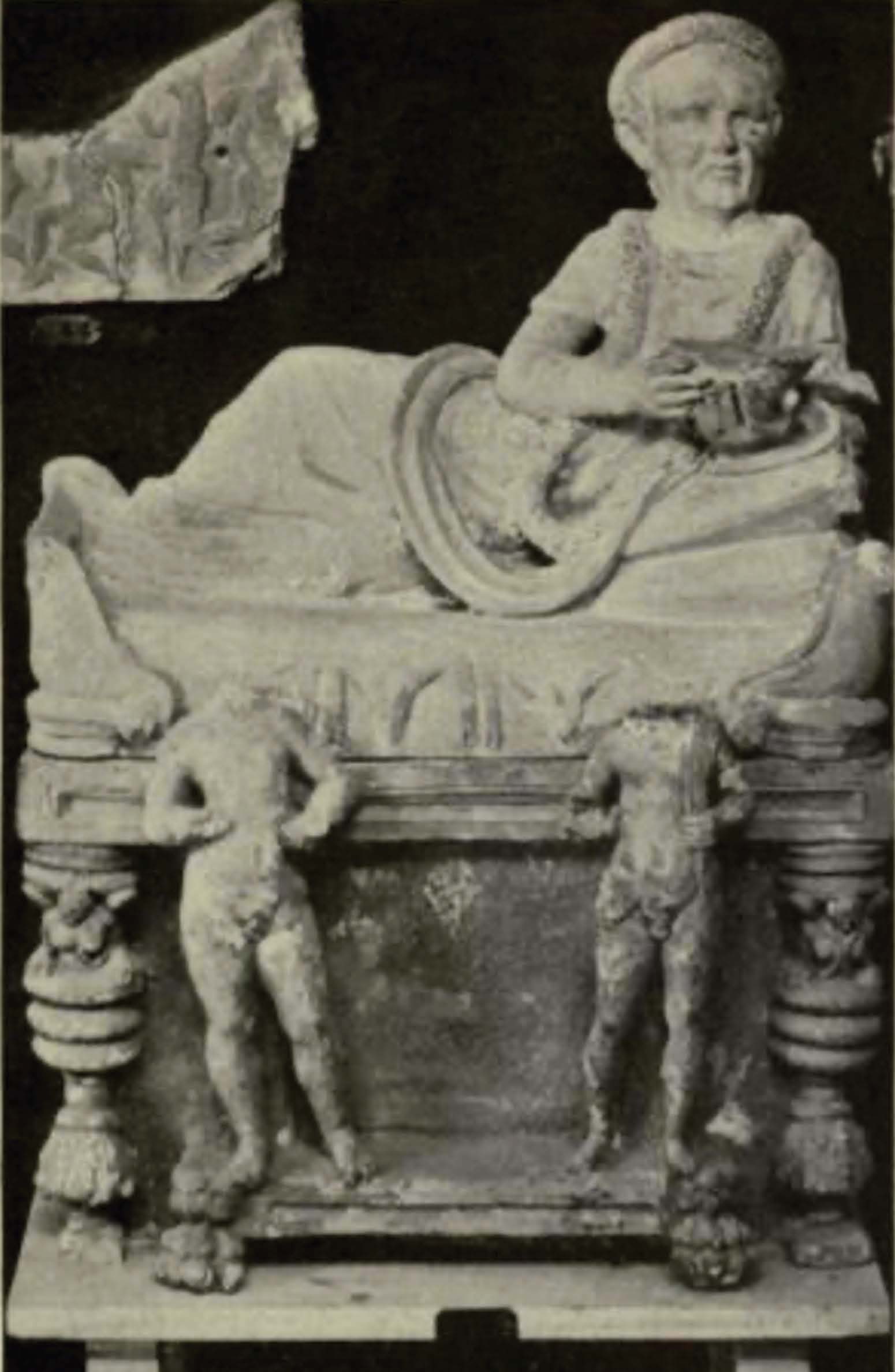

Such a sumptuous bed may have been invented by the painter following the concept of creating a suitable support for a holy man, even though a gold bed was an unlikely presence in the widow’s house. But a detail suggests that the representation was inspired by a real object: a yellow platform, matching the structure of the bed, is placed on the floor below the couch in such a way as to suggest depth and perspective in the otherwise mainly flat and frontal scene. This object was probably a long footstool, at once a practical aid in climbing upon the tall seat and a symbol of status (cf. Figure 4).