di, si qua est caelo pietas, quae talia curet,

persolvant grates dignas et praemia reddant

debita, qui nati coram me cernere letum

fecisti et patrios foedasti funere voltus.

At non ille, satum quo te mentiris, Achilles

talis in hoste fuit Priamo … ”

may the gods, if there is any piety in heaven that matters,

pay off these worthy kindnesses and return the reward

that is due. You have forced me to look face to face at the death of my son

and befouled fathers’ visages with death.

But not like that was the one you presume your sire, Achilles,

against his opponent Priam.” [11]

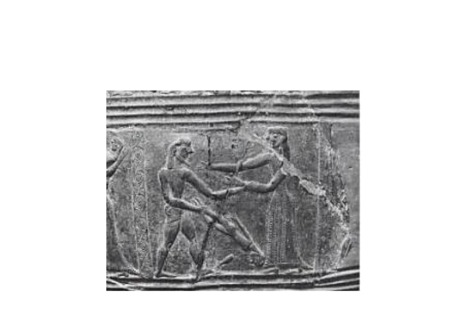

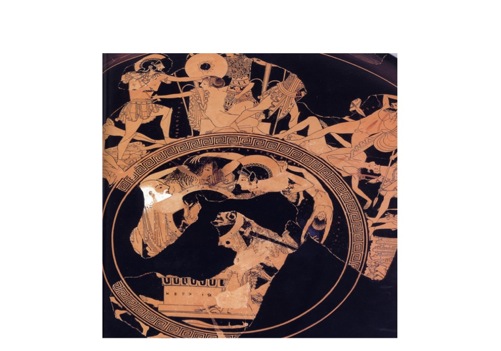

As the scene moves inexorably toward the death of Priam, Virgil first brings attention to the violation of the familial realm, with a father forced to view the death of his own son. This act alone is heinous enough, and, according to Nagy, represented in antiquity as a type of figurative blinding. [12] Indeed, according to Priam, these violations are sufficient to bring about the condemnation of the gods.

Pelidae genitori; illi mea tristia facta

degeneremque Neoptolemum narrare memento.

Nunc morere.” Hoc dicens altaria ad ipsa trementem

traxit et in multo lapsantem sanguine nati …

to my father, son of Peleus; of my grievous actions

and his degenerate Neoptolemus be sure to tell.

“Now die!” Uttering this he dragged the trembling Priam to the high altar

as the king slipped in the copious blood of his son.

οὔτ᾽ αὐτὸς οὔθ᾽, ὥς φασιν, οὑκφύσας ἐμέ.

ἀλλ᾽ εἴμ᾽ ἑτοῖμος πρὸς βίαν τὸν ἄνδρ᾽ ἄγειν

καὶ μὴ δόλοισιν …

πεμφθείς γε μέντοι σοὶ ξυνεργάτης ὀκνῶ

προδότης καλεῖσθαι: βούλομαι δ᾽, ἄναξ, καλῶς

δρῶν ἐξαμαρτεῖν μᾶλλον ἢ νικᾶν κακῶς.

nor, so they tell me, was my father. I

will freely lend myself to take the man

by force, not guile …

And yet I came to help, and would not willingly

be called a traitor. Prince, I would prefer

to fail with honor than to win by evil. [21]

Some have seen the internal conflict within Neoptolemus as evidence of an ephebic coming-of-age rite where young men are initially put through tests that require guile and deception, [22] but this analysis fails to capture the psychological complexity inherent in Neoptolemus’ actions throughout the play. When Neoptolemus acquiesces to the plan of Odysseus only to reverse course when faced with the pleas of the suffering Philoctetes, Sophocles shows us what can happen when the young man’s inherited qualities, both real and perceived, come into conflict with the actual “dilemmas of life.” [23]

γέ[ρον]θ̣’ ὅ̣[τι] Πρίαµον π[ρ]ὸς ἑρκεῖον ἤναρε

βωµὸν ἐ[πεν]θορόντα, µή νιν εὔφρον’ ἐς οἶ[κ]ον

µ̣ήτ’ ἐπὶ γῆρας ἱξέµεν βίου· ἀµφιπόλοις δὲ

µυριᾶν περὶ τιµᾶν δηρι]αζόµενον κτάνεv

<ἐν> τεµέ]νεϊ φίλῳ γᾶς παρ’ ὀµφαλὸν εὐρύν.

<ἰὴ> ἰῆτε νῦν, µέτρα π̣αιηόν]ων ἰῆτε, νέοι

that because he had killed aged Priam as he leapt towards the alter

of Zeus Herkeios, he would reach neither his kindly home

nor old age in life. As he quarreled over his vast prerogatives Apollo slew him

in his own sanctuary by earth’s broad navel.

Ie, sing ie now—measures of paeans—sing ie, young men

Here, the poet compresses together the slaughter of Priam and the symmetrical punishment of Neoptolemus, where, as Nagy has pointed out, the focus is on the antagonism between hero and god: “Since ‘Paean 6’ was composed specifically for a Delphic setting and in honor of Apollo, we should be especially mindful of the central role of its hero as the ritual antagonist of the god. For we see here a striking illustration of a fundamental principle in Hellenic religion: antagonism between hero and god in myth corresponds to the ritual requirements of symbiosis between hero and god in cult.” [37]

Figures