Cholevas, Michalis, Andrew Watson, and Anna Apostolidou. 2025. “Affective Affinities in Eastern Mediterranean Poetry and Music: An Online Performance.” In “Emotion and Performance in Late Antiquity and Byzantium,” ed. Niki Tsironi, special issue, Classics@ 24. https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HLNC.ESSAY:104135597.

Abstract

Introduction

Translation (in) Process

It is notable that both poems separately refer to the possibility that both gods and souls of the dead may simply be ideas that respond to human need and that have no concrete existence in themselves. [3] In “Olympia” there are the following lines toward the end of the poem:

and the old world brings a new one

on the path laid by

each man’s need.

In “All Souls’ Day” a similar point is made:

to them they mean nothing.

Perhaps the only purpose of these myths of divinities or souls of the departed is to bring comfort to human beings who suffer a sense of abandonment in this natural world.

Preparation and Analytic Course

Performance Context

Crafting Melodic Promenades

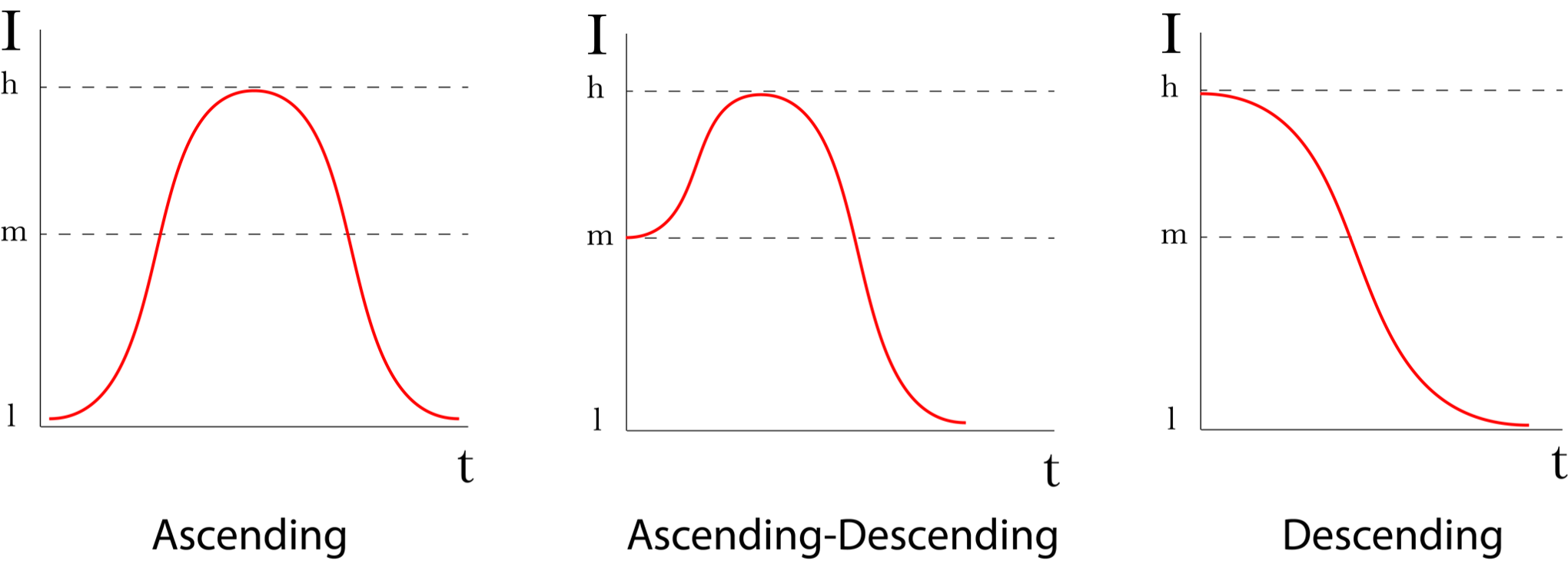

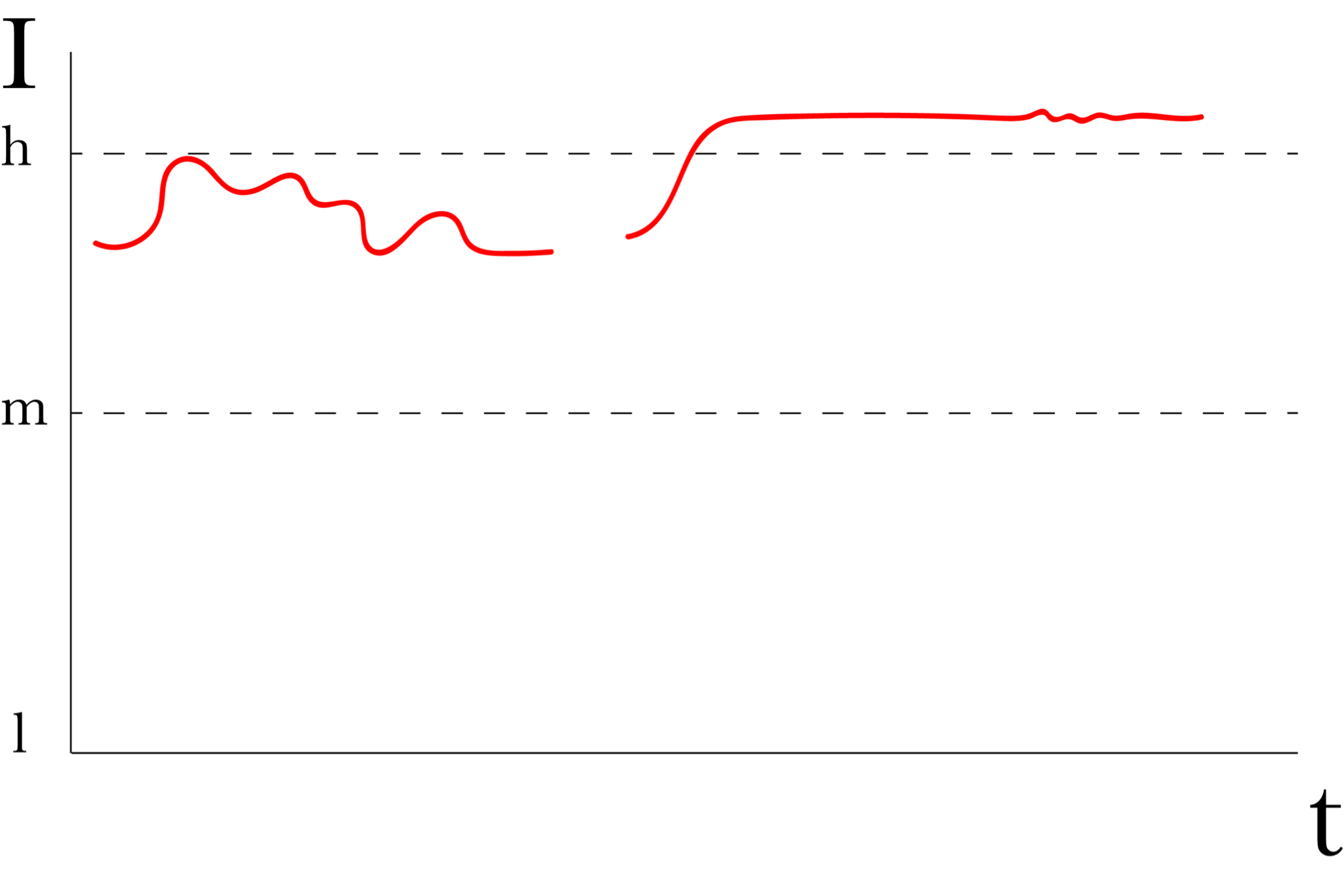

In the makam tradition, largely developed in the Ottoman Empire and maintaining powerful affinities with arabic maqams and Byzantine ήχοι, there are three predominant shapes of melodic development found in the melodic shape of both compositions and taksim (improvisation) performances: a) ascending; b) ascending-descending; and c) descending (see Graph 1).

Distinctive Intensity Curves I: Easter at Olympia

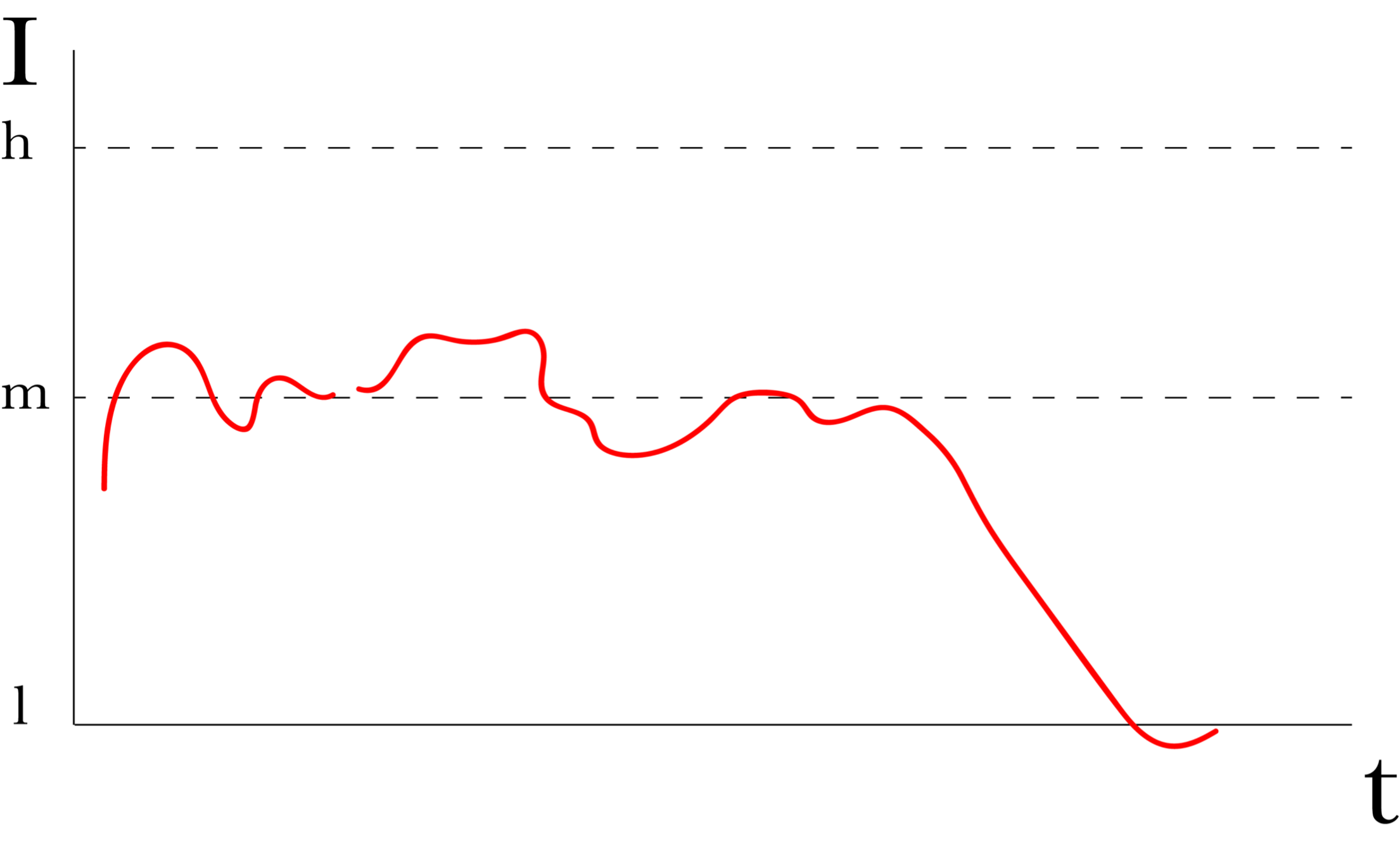

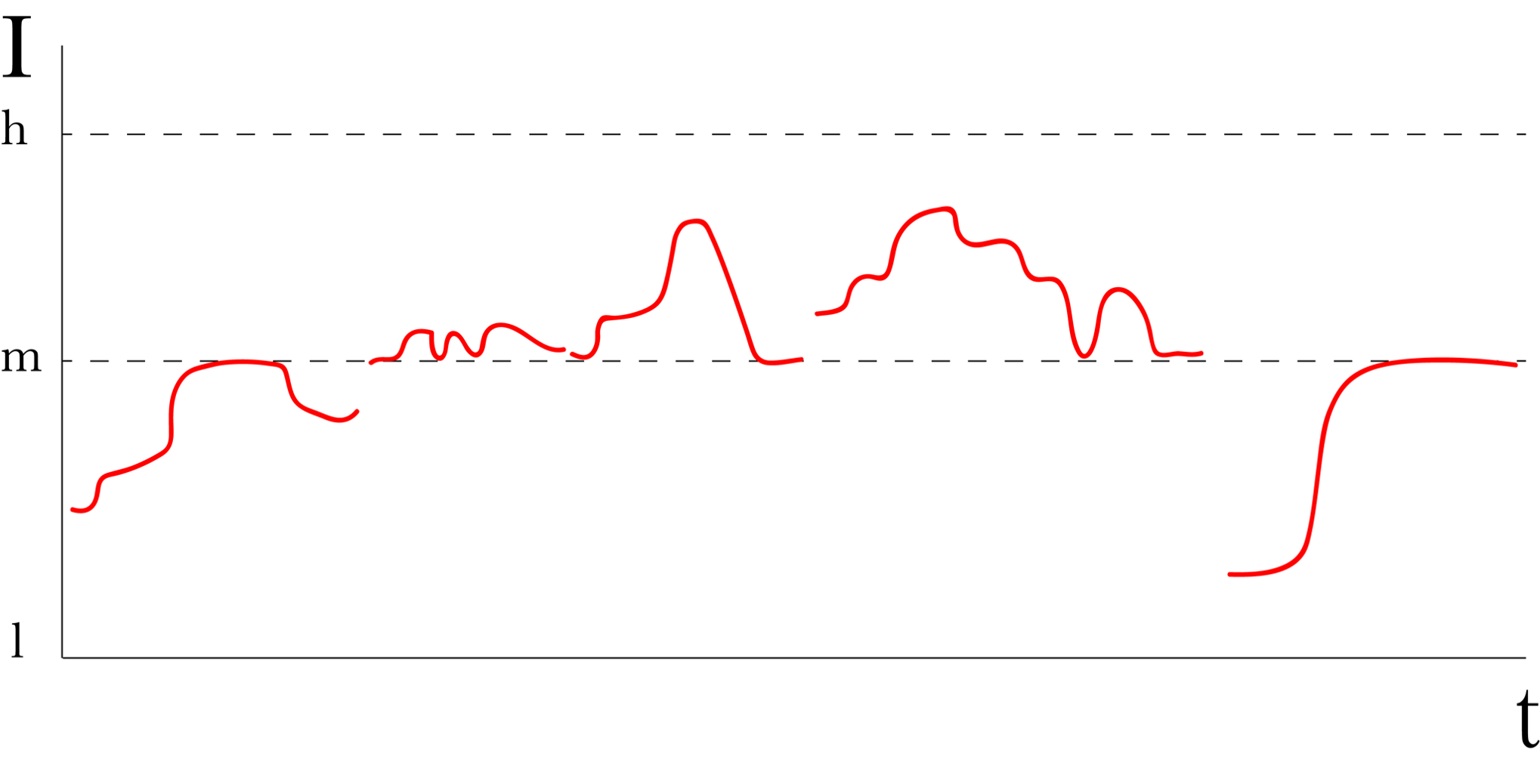

Then we defined a flexible sequence that, much like the seyir, would pave the way for the unfolding of the improvisation. Note in this example how the first phrase introduces the middle and low tonal part with the intention to bring Andrew Watson to the lower part of the emotional curve for the beginning of the recitation of the poem, in accordance with the ascending-descending character of Makam Huseyni (Graph 2).

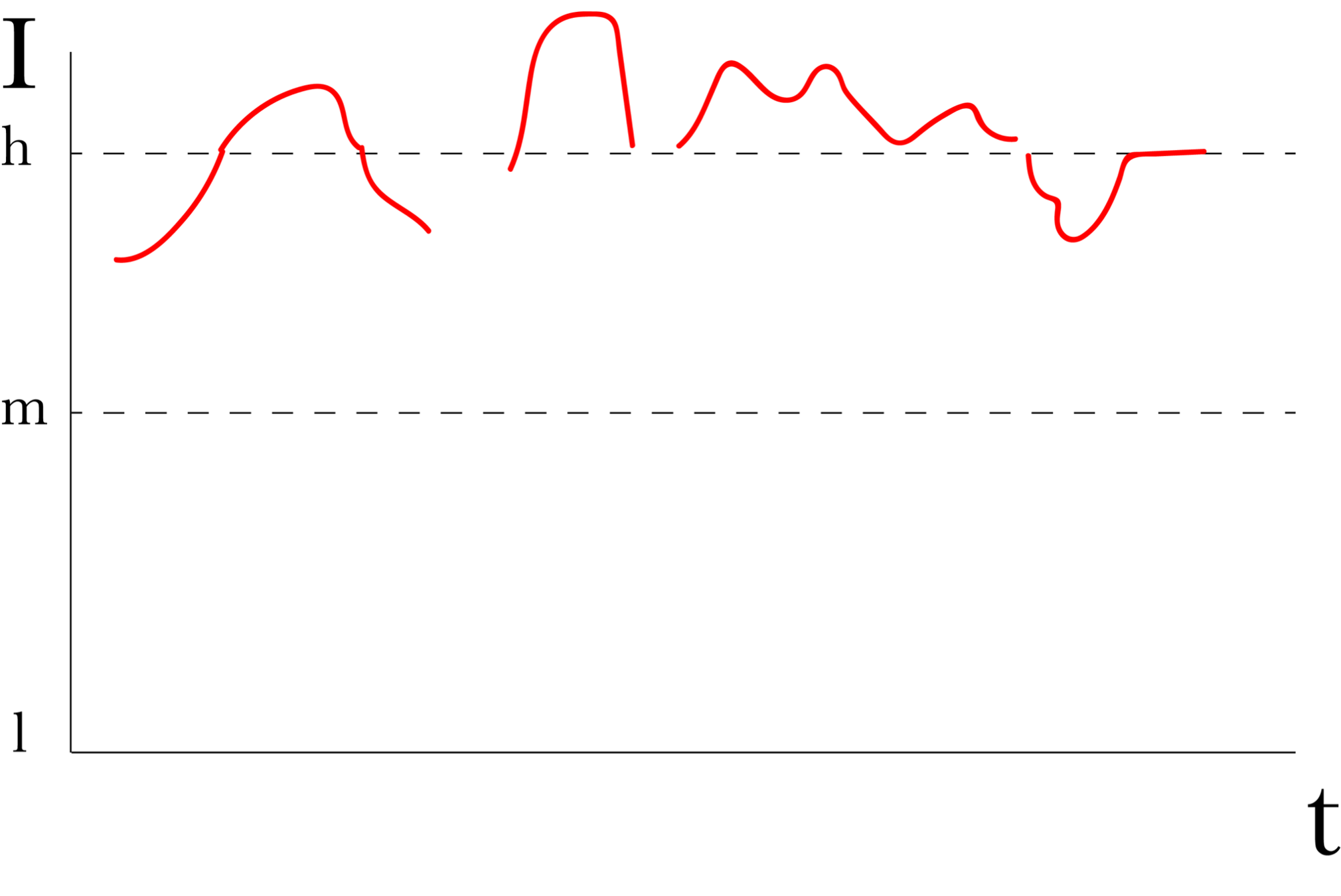

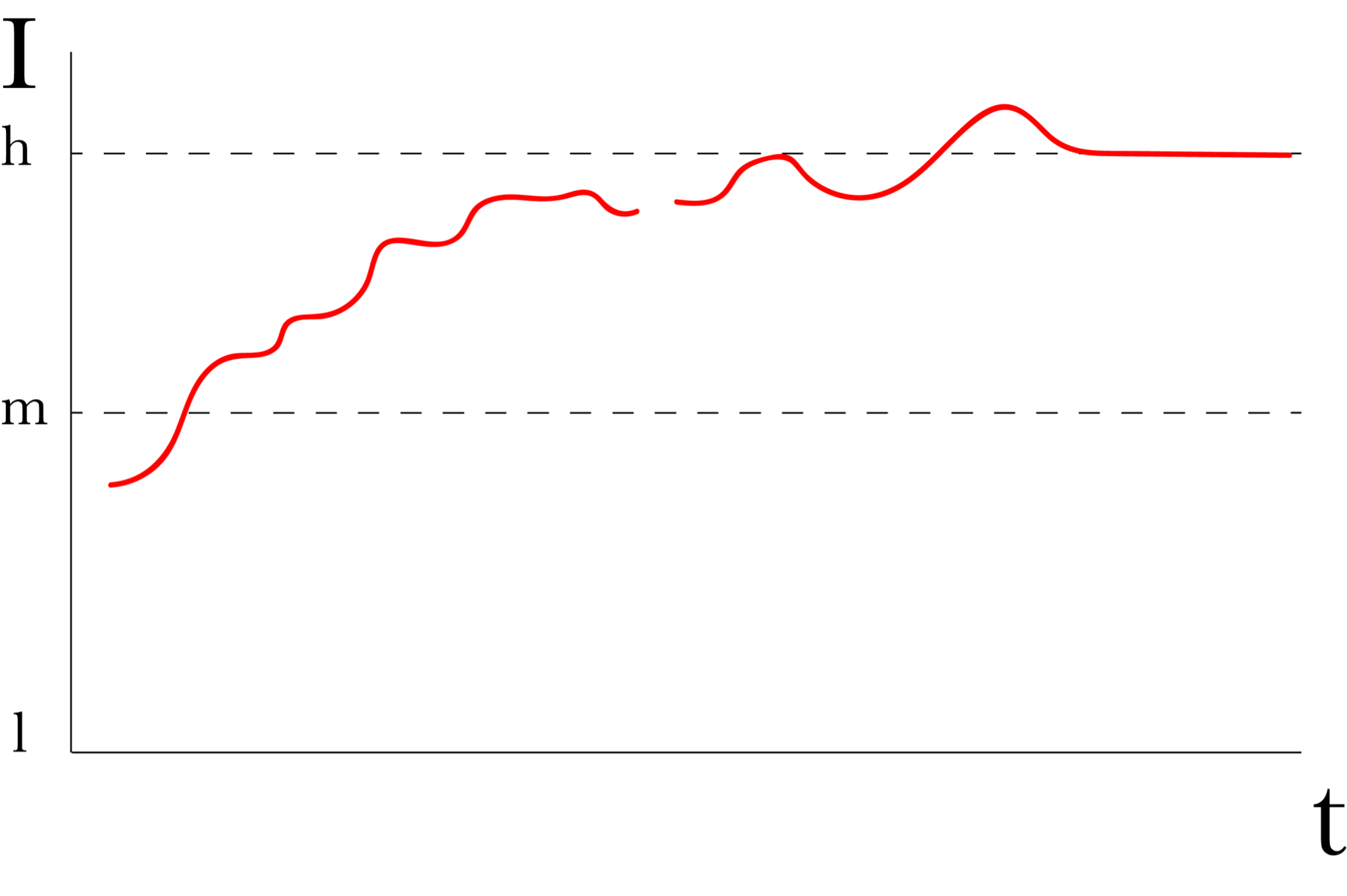

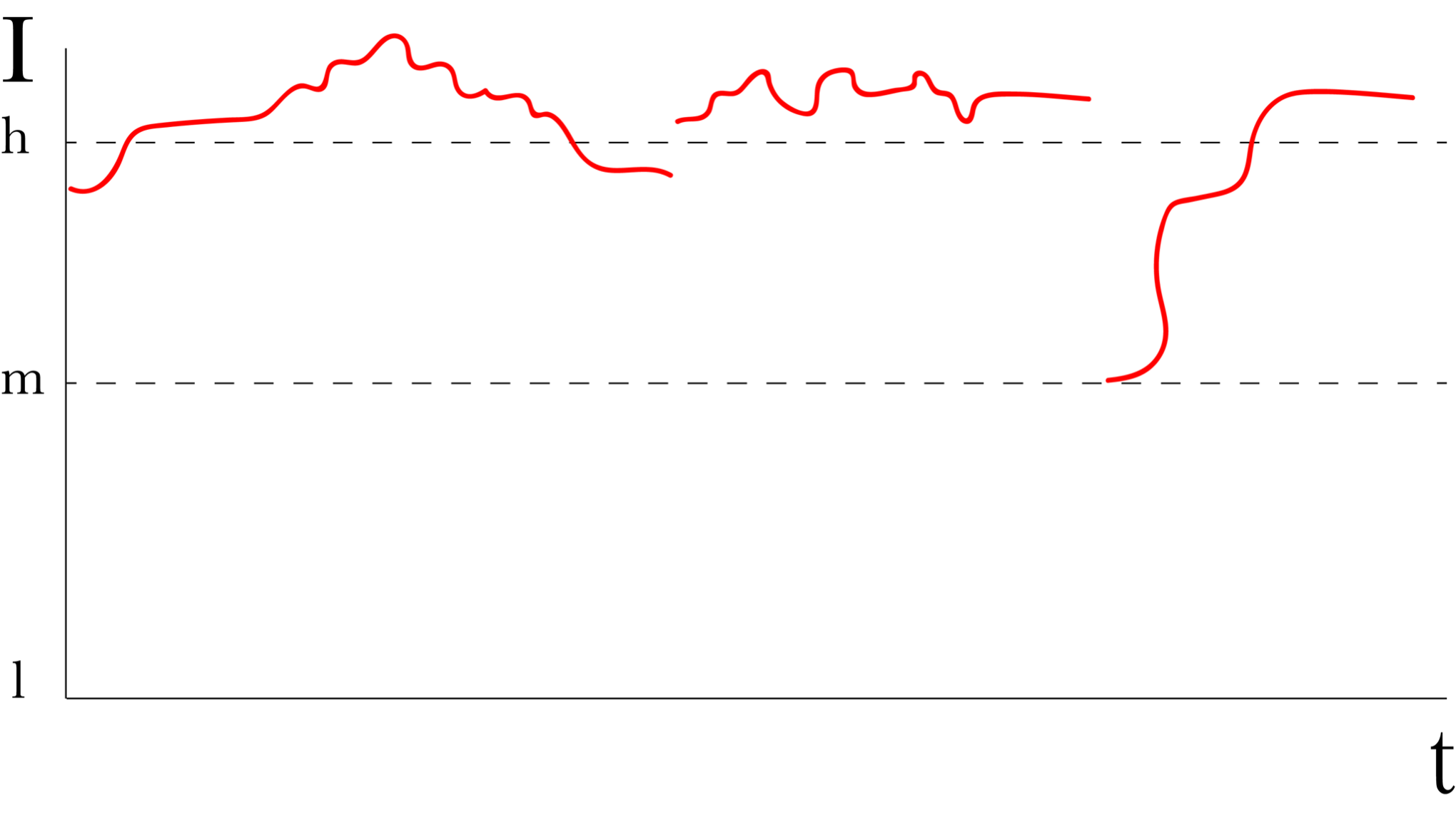

The second phrase moves the intensity to the highest part of the spectrum, in an attempt to capture the high intensity of what the performers identified as a point of great emotional and imagery concentration in this particular poem (Graph 3).

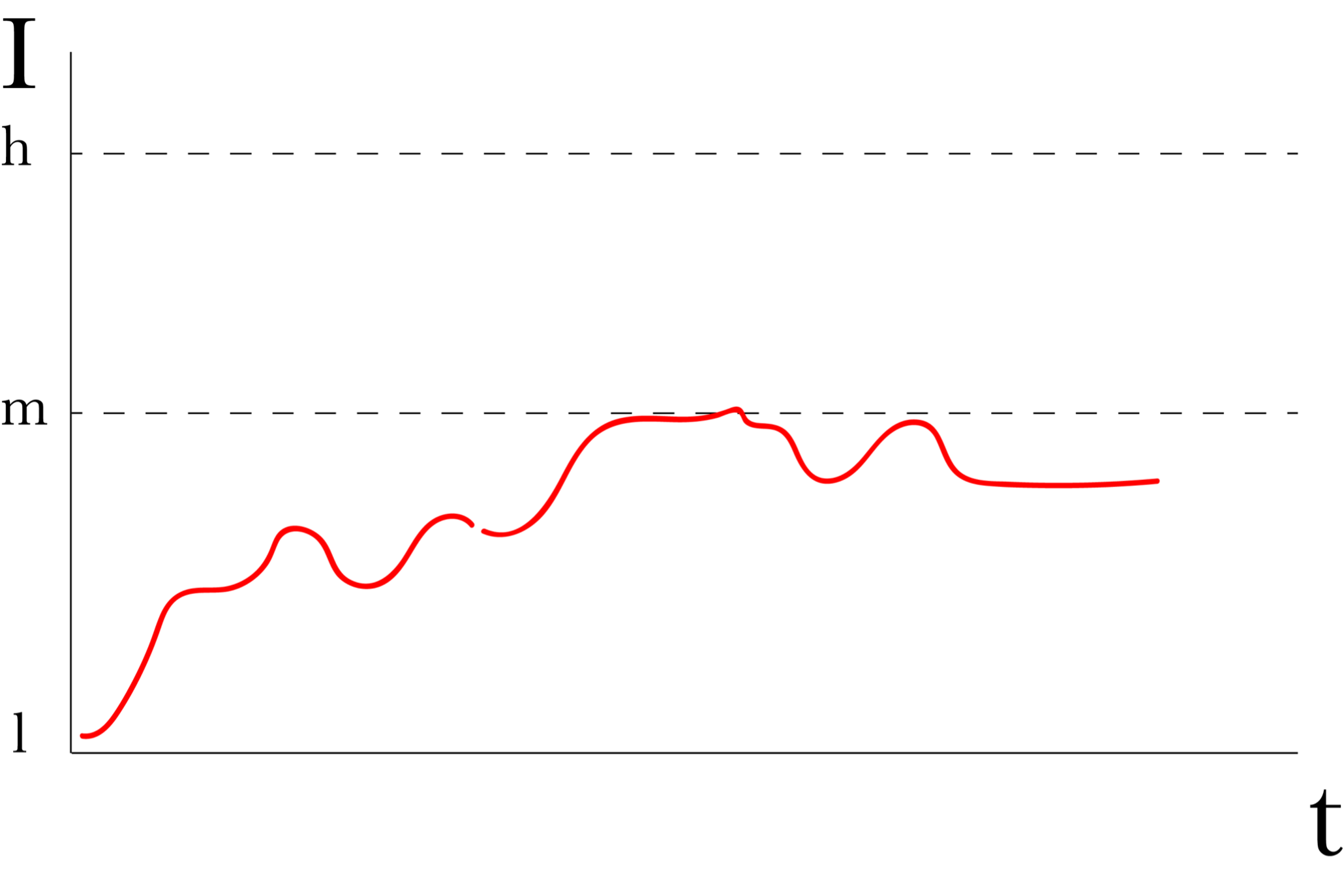

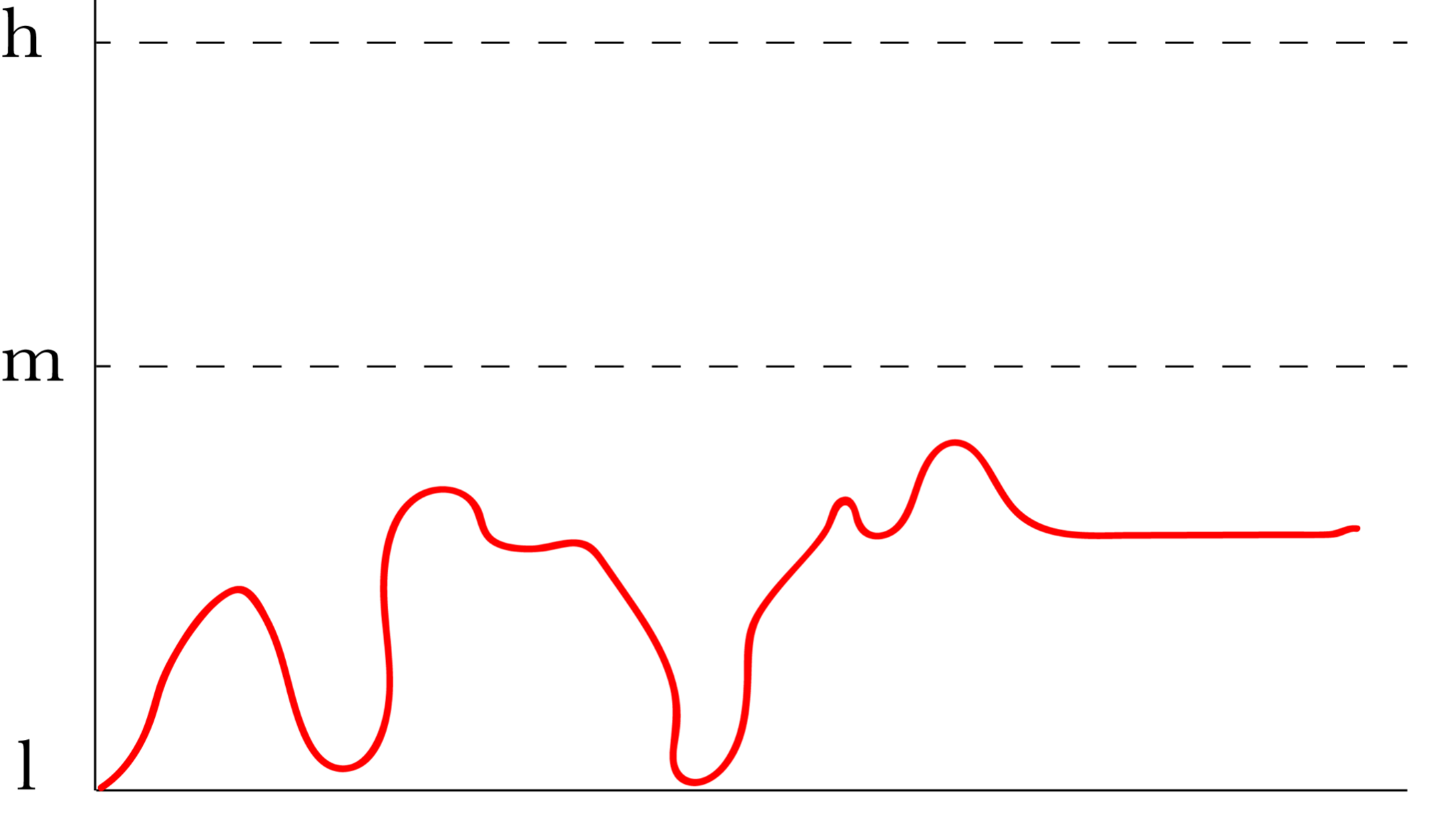

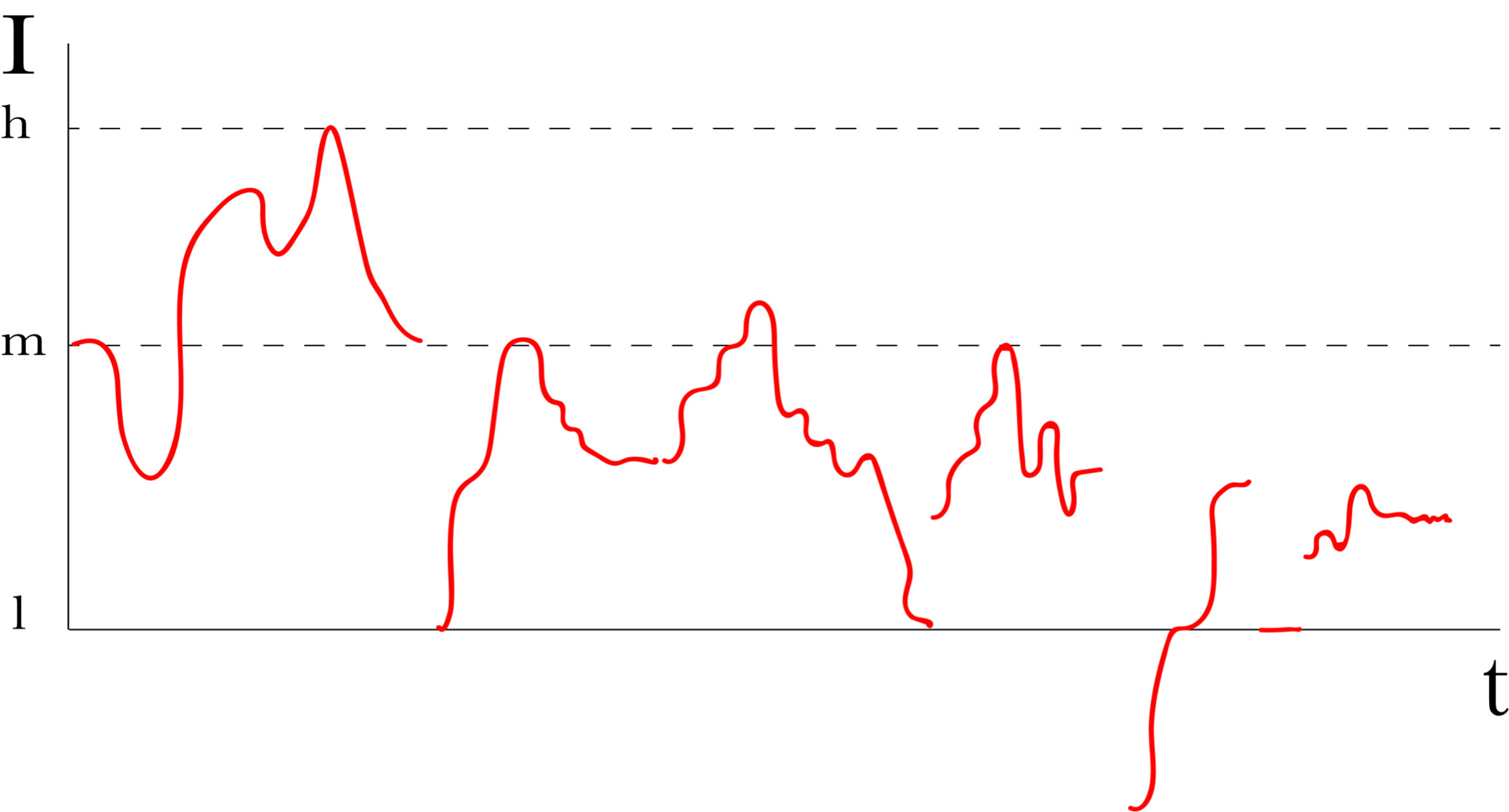

The second phrase is followed by an interplay between poetry and music, signifying a need for the voice and the taksim soundscape to coexist in a common aural space. The third yayli tanbur phrase is maintaining that middle level of intensity and prepares for the elevation that follows immediately after (Graph 4).

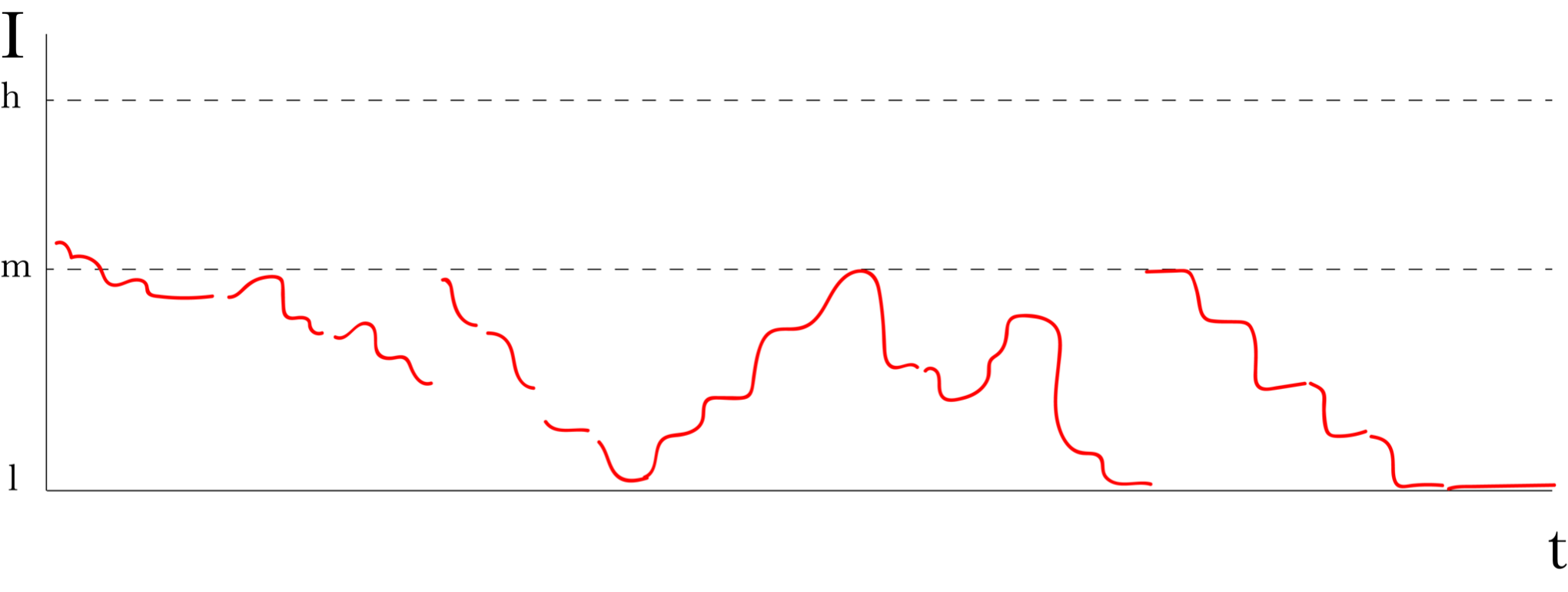

The concluding phrase is performed in order to prepare for the closing with a feeling of relaxation, even relief and regeneration, as the last stanzas imply, and therefore the music is gradually descending to the tonic, the lowest part of the intensity curve (Graph 7).

Distinctive Intensity Curves II: All Souls’ Day

Specifically, the opening phrase had the intention to set a suspended mysterious feeling that leaves a lot to the listener’s imagination, introducing the main gravitational center of the section’s mood (Graph 8).

The second phrase of the yayli tanbur (“reconciled with them”), a connection between the first and second verse of the poem, moves to the middle area of Segah, signaling a brighter color and a raise of intensity both because of higher pitch as well as due to the use of softer intervals [12] (Graph 9).

The yayli tanbur stayed involved performing on the background of the text and preparing the conclusion by descending from the upper part of the mode to the middle part. The last words recited by Andrew (“In our dream the earth, only the earth and the blackbird’s song”) signaled the final musical conclusion and the return to the base of the makam, closing the ascending form of makam’s route and fading away with the intention to leave the audience with a feeling of emotional exaltation (Graph 11).

Tracing Affinities in Performative Ways

Our expressive choices and the development of the performance have been informed by a genealogy of cultural elements, which we have found to be commonly evident in the poetry of Giorgos Gotis, in its forceful depiction of mundane ritual and local cosmology, and also imbued in the Makam music tradition, which sprung from the amalgam of music practices of the Eastern Mediterranean region. The work of Valiavitcharska on the Byzantine and Old Church Slavonic rhetoric rhythm has recently brought to light the profound properties of sound and rhythm, challenging the entrenched separation between content and style and emphasizing the role of rhythm as a tool of invention and a means of creating shared emotional experience. [16] Along the same lines, McGuckin has demonstrated the pivotal role of poetry and music in Christian Spirituality in Byzantium and the East Mediterranean. As he notes in reference to the Syrian style of poetic rhetoric vis-à-vis the Christian liturgical tradition in the case of Romanos the Melodist: