Vroom, Joanita. 2025 “The Unbearable Brokenness of Artifacts: Dining Utensils as Social Markers of Performance in the Byzantine World (ca. seventh-fifteenth centuries).” In “Performance and Performativity in Late Antiquity and Byzantium,” ed. Niki Tsironi, special issue, Classics@ 24. https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HLNC.ESSAY:104135620.

Introduction

Conspicuous consumption: Byzantine banquets

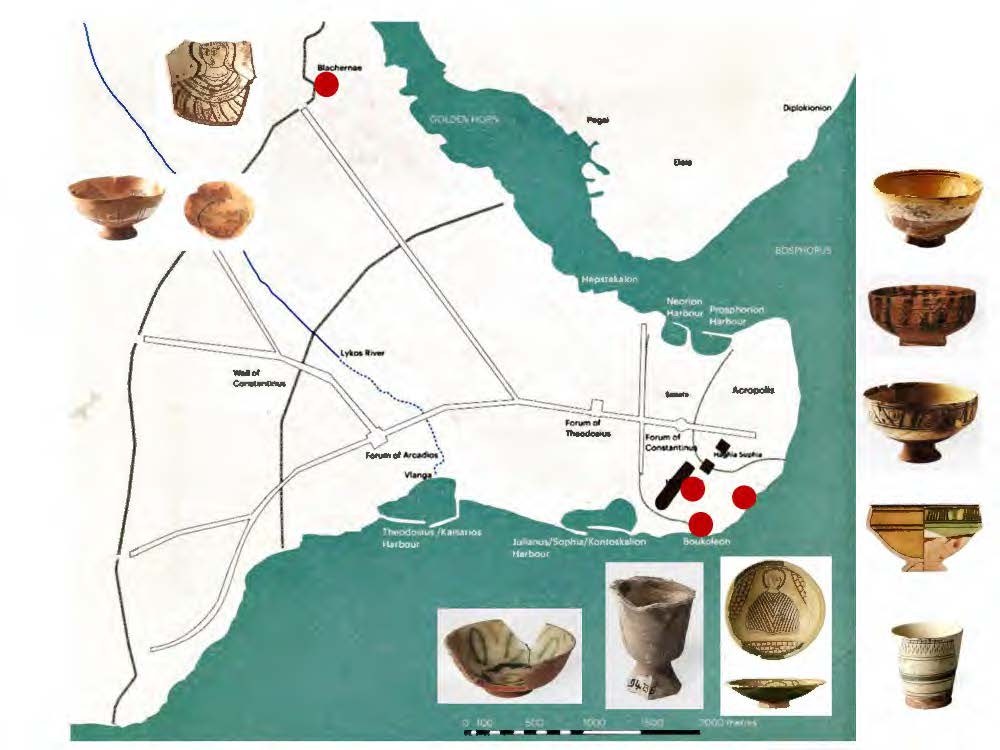

The first manuscript is the tenth-century ceremonial text De Cerimoniis or “Book of Ceremonies,” compiled by the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII (913–959). It describes a renewal of court ceremonial and offers a vivid picture of how the physical space of the Great Palace was experienced in court ceremonies, by meticulously describing processions, receptions, and banquets. [8] The second text is the Kletorologion or “Banquet Book” written by Philotheus and dated to 899, [9] and the third one is the much later Palaeologan treatise by “Pseudo-Kodinos” dating from the mid-fourteenth century. [10] The first two documents mention various reception and dining halls in the Great Palace at Constantinople, such as the Chrysotriklinos, the Ioustinanos, “the great Triklinos of the Magnaura,” and “the Triklinios of the 19 couches.” This last hall offered for instance space to approximately 229 guests with the Emperor dining at the imperial high table in the apse (Figure 1, upper left; cf. Table 1 for the locations of these halls). [11]

| Part of the Great Palace | Dining seats | Dining tables | Dining utensils | Adornments | Other | Purposes |

| Chrysotriklinos (lower terrace) | Throne(s); a golden chair (sellion) on its left side; a chair (sellion) covered in purple silk on its right side; golden couches | Separate table for Emperor; golden table; tables | Golden platters; large silver serving bowls in repoussé; small bowls in repoussé; golden bowls with precious stones | Golden curtains; bright-purple curtains (with griffins and asses); hangings | Kitchens; silver organs; silver polykandela; floor strewn with myrtle, rosemary and roses | Throne room; audience hall; promotions of imperial officials; banquets; everyday procession |

| Ioustinianos (lower terrace) | Throne; golden sellion; benches | Separate table for Emperor; tables | Hand basins in repoussé; silver plate | Curtains | Two silver organs; hand towels; perfumed waters and oils; polykandela | Reception hall banquets; lunch |

| Aristeterion (lower terrace) | Small golden table | Enammelled bowls encrusted with precious stones | Dessert | Breakfast room | ||

| Triklinos of the 19 Couches (upper terrace) | Reclining on couches; mattresses | Round side table | Curtains | Organ; cymbals; saximon | Large banquet hall; funerals; promotion of ‘Caesar’; Christmas festivities; still functioning ca. 1040 | |

| Magnaura (upper terrace) | Throne of Solomon; golden portable seats (sellia) | Silver works/objects in repoussé; golden and enammelled objects | Embroidered curtains; Persian covers | Golden organ; silver organs; silver polykandela; floor sprinkled with rose-water | Throne room; state receptions; banquets | |

| Kathisma in Hippodrome (upper terrace) | Carpets; curtains | Dining hall; bed chamber; races/games functioning until end of 12th c. |

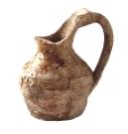

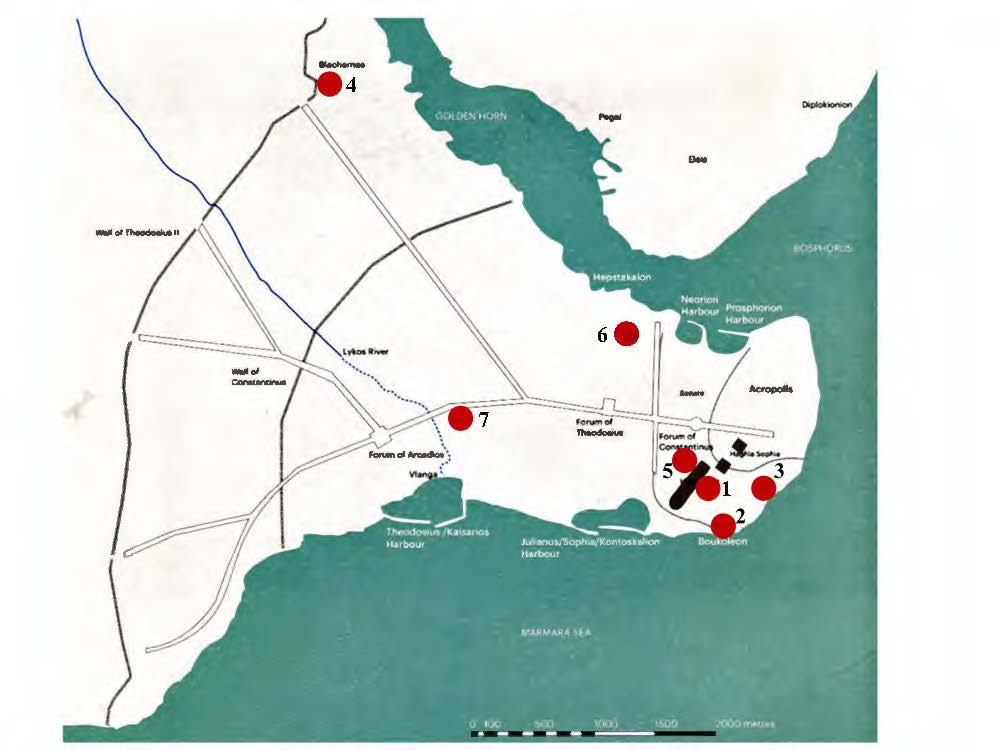

To get some sort of an idea of how these priceless objects must have been used as part of the performance during tenth-/eleventh-century banquets and religious ceremonies at Constantinople, one could nowadays pay a visit to the San Marco Treasury at Venice or the Kunsthistorisches Museum at Vienna and gaze at the Byzantine artifacts on display, a glittering collection of objects made of glass or sardonyx, enriched with gold cloisonné enamel, precious stones, and stunning rock crystal. [19] Other Middle Byzantine food-related artifacts kept in the San Marco treasury at Venice, among which prestigious chalices and dishes (paten) made of alabaster, sardonyx, and Islamic glass, also point in the same direction of dining as dazzling performance. [20] Especially in the three main imperial places at Constantinople (the Great Palace, the fortified Boukoleon Palace, and the semi-suburban Blachernae Palace), [21] such imposing vessels would have been used as social markers or even as some sort of stage props during banquets, receptions, and ceremonies (Figure 2). However, here the focus is not so much on these precious objects made of high-status materials, but rather on the more mundane ceramic artifacts found in the excavated remains of these Byzantine palaces in the imperial capital (Table 2). [22]

Deep fakes and cheap fakes: Pottery as social imitation

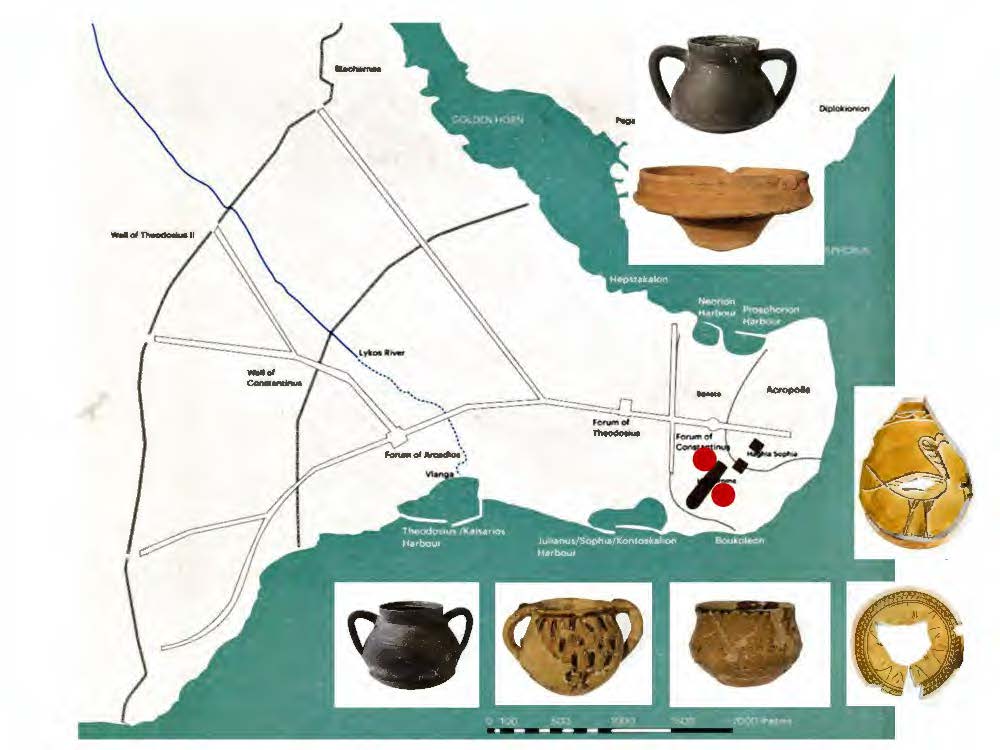

Among the ceramic finds excavated at Constantinople dating from the Early Byzantine era (ca. the seventh to early ninth centuries), of particular interest are in this respect unglazed domestic utensils for food preparation (such as cooking pots and mortaria) which are part of pottery assemblages retrieved from two palaces in the heart of the city: the Palace of Antiokhos and the Great Palace (Figure 3). [26] The last one also yielded locally made glazed dishes, bowls, and a double-handled pot of so-called Glazed White Ware I, the first glazed product par excellence made in Constantinople (Figure 3). [27] Initially, Glazed White Ware I was merely imitating the shape of cooking pots, but eventually became more and more decorated with petal applications and simple incised motifs for use on the table. [28]

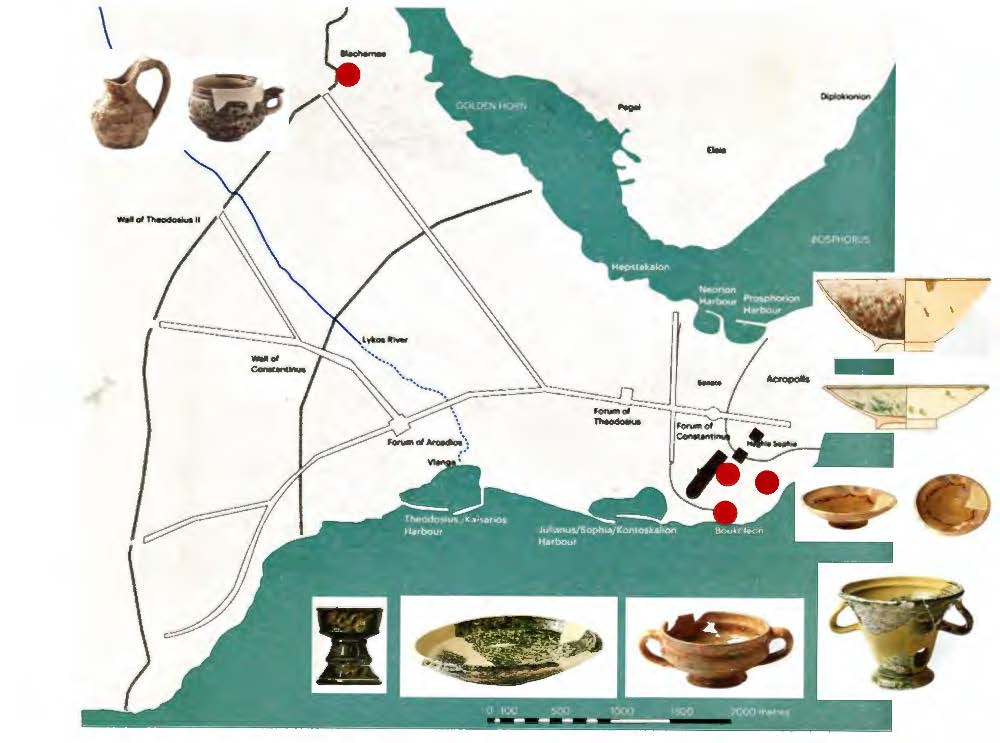

Ceramic finds of the Middle Byzantine era (ca. ninth to eleventh centuries) from four excavated palaces at Constantinople show, on the other hand, a larger amount and a wider variety of glazed tableware shapes (mostly of the Glazed White Ware II and Polychrome Ware repertoire with elaborate incised or painted motifs), which were probably used on or next to the table (Figure 4). [29]

These finds included large dishes, broad shallow bowls, and wide-rimmed drinking vessels, as well as chalices, cups, and chafing dishes. [30] It is clear that the practice of using decorated glazed pottery for table purposes—even in the imperial palaces—became more widespread in this period. From the perspective of dining habits, however, not only the decoration is significant, but in particular the increase of large, open, and shallow forms. The archaeological record, which thus shows a change in the pottery repertoire towards large dishes and shallow bowls, raises all sorts of questions concerning their actual use and changes in dining practices.

Pictorial evidence: Eating with hands at the Last Supper

From the perspective of material culture, the increase of large open forms in the Middle Byzantine pottery finds from palaces at Constantinople clearly suggests that the dishes and bowls were meant for communal dining rather than for individual dining. [31] This seems to be confirmed when we compare these actual finds with the depiction of dining scenes on Middle Byzantine miniatures, which show without exception just one large plate placed centrally on the table (Figure 5). [32]

This dish was apparently used communally for the main course by the diners, who were partly reclining or partly sitting around a semicircular table. By then, some guests are reclining on coaches, which was a dining custom deriving from Late Antiquity and in Byzantine times a mark of high status. This dining position was certainly a privilege for guests of honor, which would be seated in special places—often in the right and left corners of the table. [33] Evidently, there were no knives, spoons, or forks on the table, which implies that all guests used only their fingers to eat directly from the shared central plate or bowl. This also makes sense: using one hand only while dining would be more convenient in a reclining position at the table.

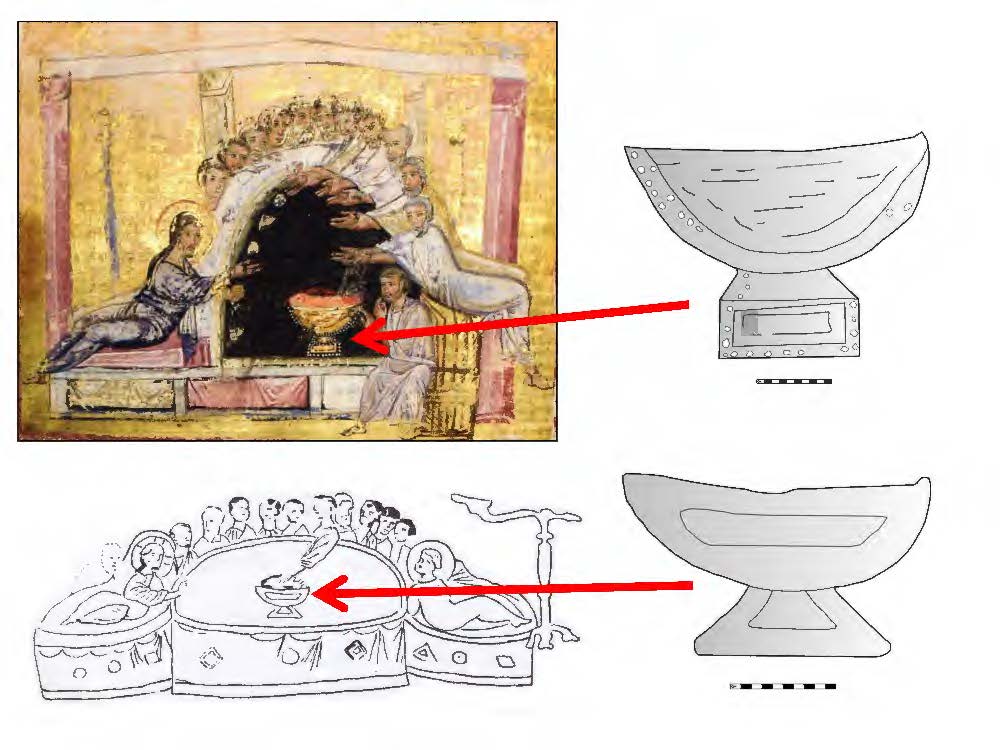

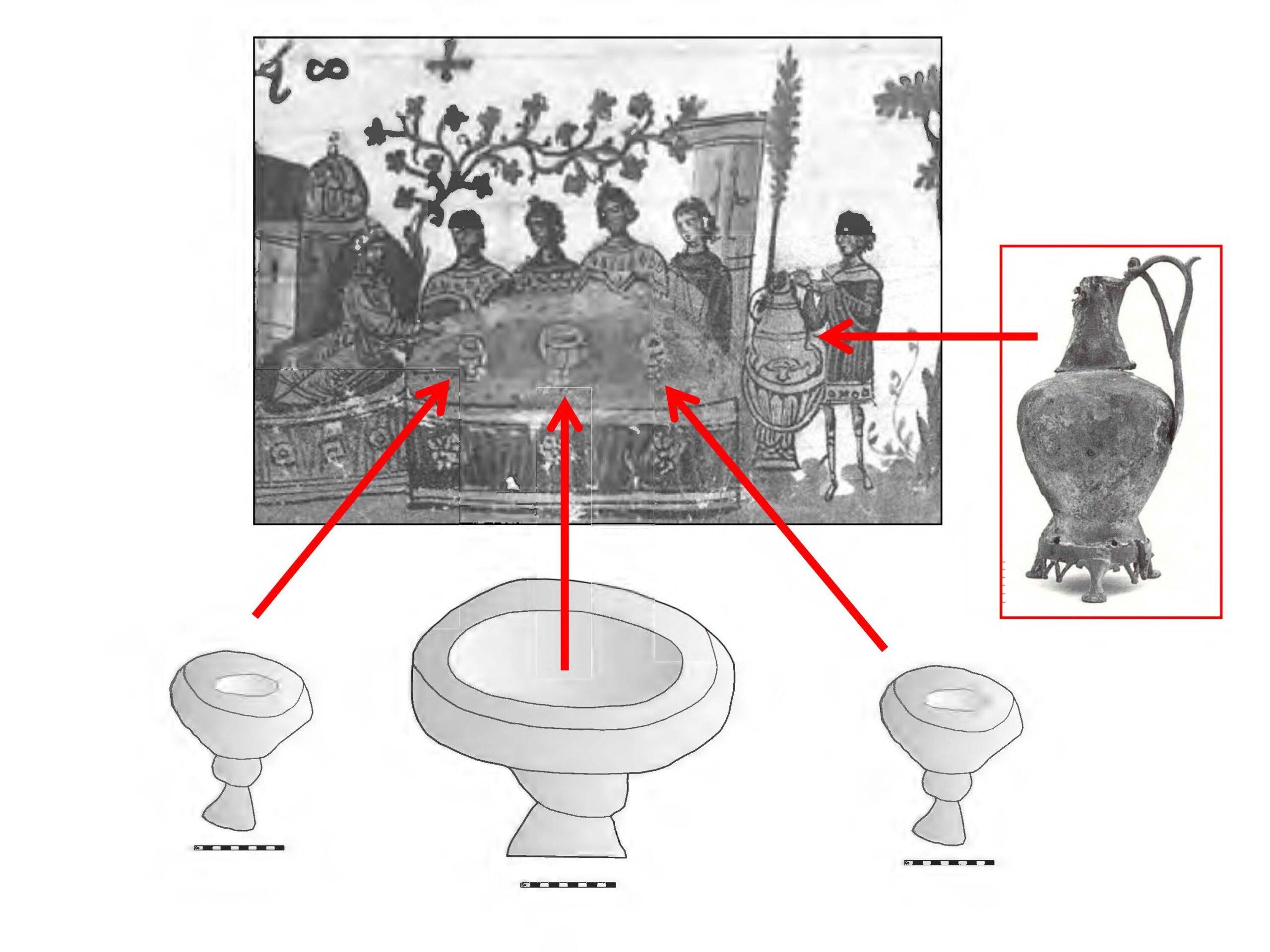

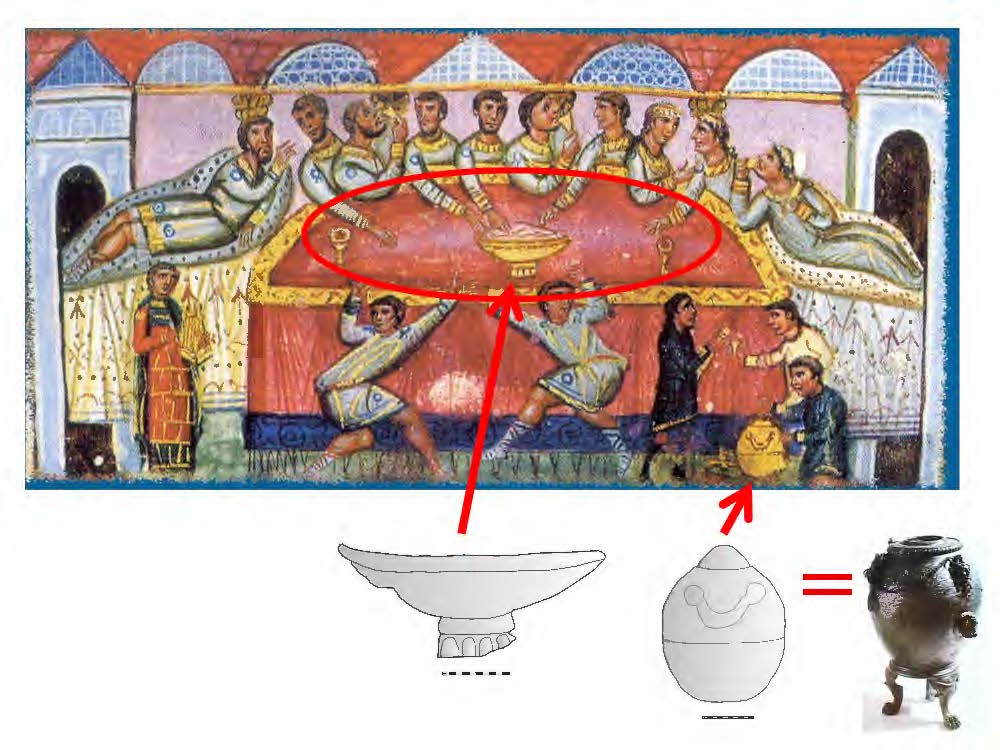

In fact, other dining scenes on miniatures in eleventh-century Byzantine manuscripts, which do not depict the Last Supper, but for example scenes such as “the feast of Herod” or “Jesus sitting in the House of Simon the Leper,” show each and every time the same pattern of diners reclining and sitting around a large, oval table with one (ostensibly) communal plate or dish in the center. [35] On most miniatures, one may notice an interesting addition of two cups or chalices (perhaps for drinking?) next to the open, communal dish on the table (Figure 6).

On a few miniatures, one can even distinguish a realistic-looking authepsa next to the table (Figure 6, right). This was a metal samovar used for heating water that was meant to be mixed with wine for drinking purposes, as is attested by similar-looking examples with intricate interiors excavated in western Turkey, Italy, and Nubia. [36]

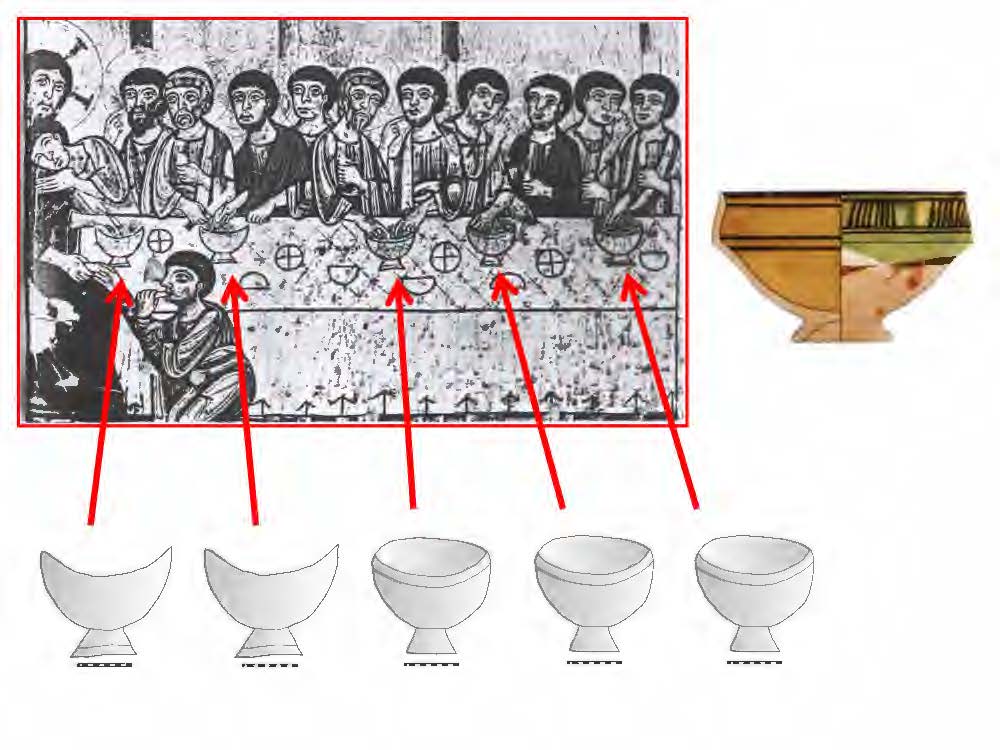

The combination of one dish flanked by two cups/chalices can be seen on many Middle Byzantine miniatures with dining scenes, including depictions of the Last Supper, strongly suggesting communal wining and dining. [37] In fact, an eleventh-century miniature of Job’s Children from St. Catherine’s Monastery at Sinai in Egypt shows for instance—apart from the one large communal plate and two communal cups—the act of communal dining itself: five of the ten diners actually grasp with their hands towards and into the centrally placed dish (Figure 7). [38] In addition, this miniature shows again the use of an authepsa during the meal; this time made in a more old-fashioned style in front of the table (Figure 7, lower right). [39]

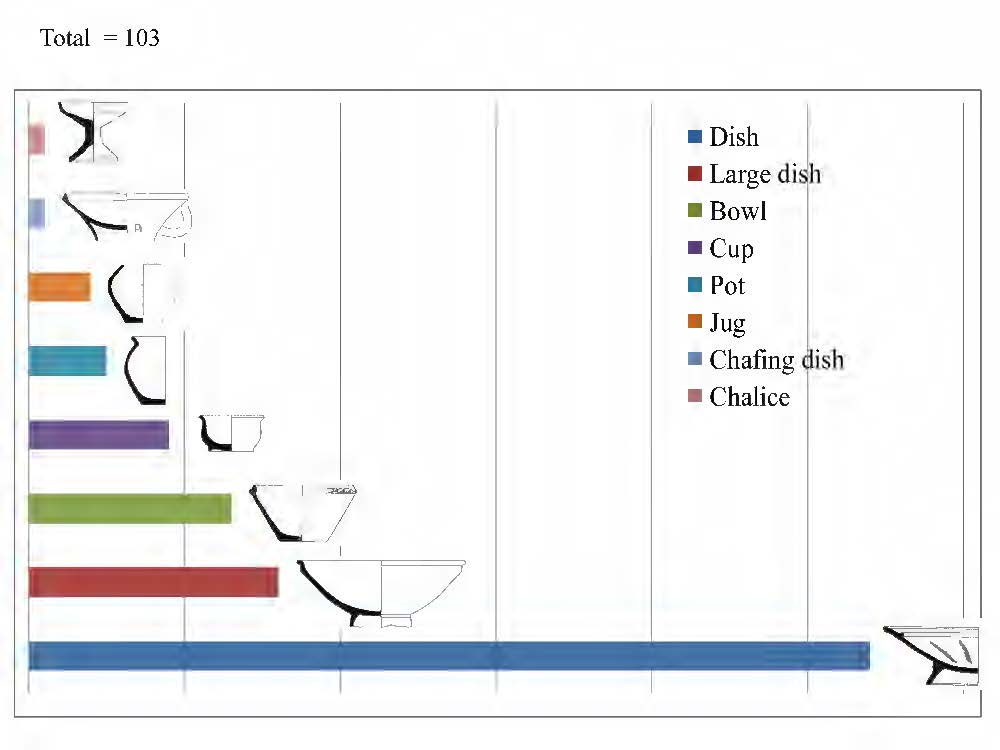

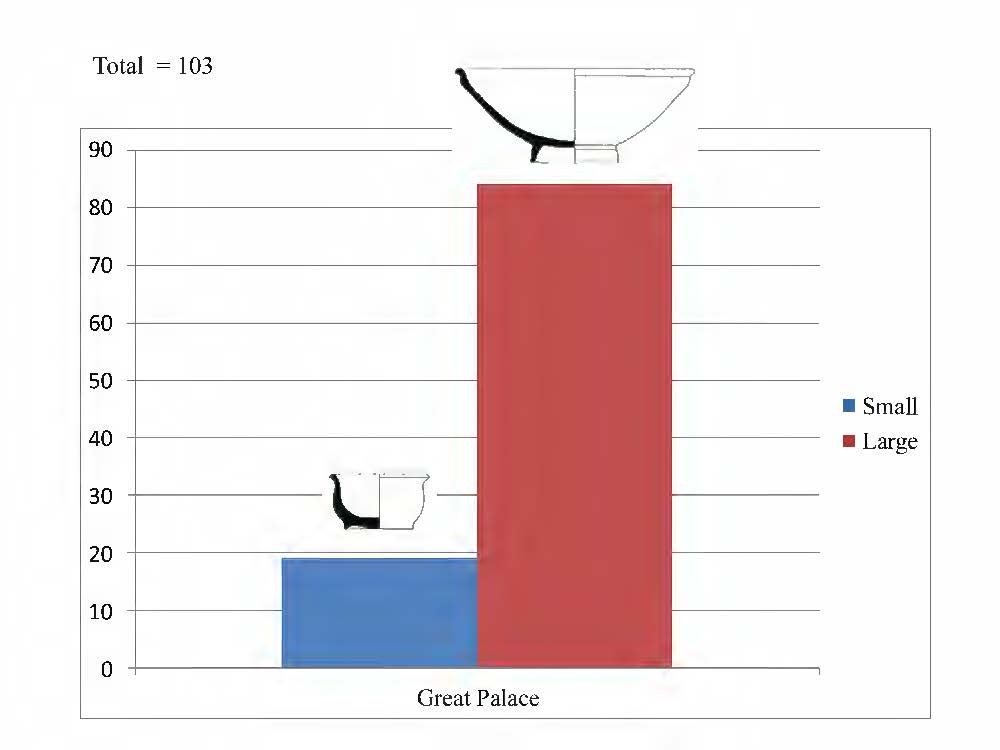

As far as the shapes of ceramic tableware vessels of the seventh/early-eighth to mid-eleventh centuries excavated at the Great Palace are concerned, a wide-rimmed dish on a ring foot was apparently the most commonly used vessel in this period (Figure 8). [40]

In a more general way, it is obvious that the most used shapes for tableware in the imperial palace were mutually open and large with a wide rim diameter (Figure 9).

That this typology was not confined to the imperial court alone is confirmed by similarly dated pottery vessels from other excavations in the city, among which those found at the churches of St. Eirene and St. Polyeuktos. [41]

Dining with the eyes: Late Byzantine shapes and the civilizing process

Things were about to change after the twelfth century, both in the territorial power of the Byzantine Empire and in the dining habits. A late twelfth/thirteenth-century Byzantine miniature of a Last Supper dining scene on a croce dipinta (painted cross) in the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo in Pisa (Italy) shows five bowls for the apostles, instead of one large dish in the middle of the table (Figure 10, upper left). [44]

In this way, the diners, who were sitting upright and not reclining, were sharing one small bowl between two or three men. They were apparently expected to eat together from the same bowl only with their immediate neighbors. Furthermore, the food was by now not only handled with the fingers but also with a knife, which as a table utensil became more easily accessible for diners in a sitting position at the table.

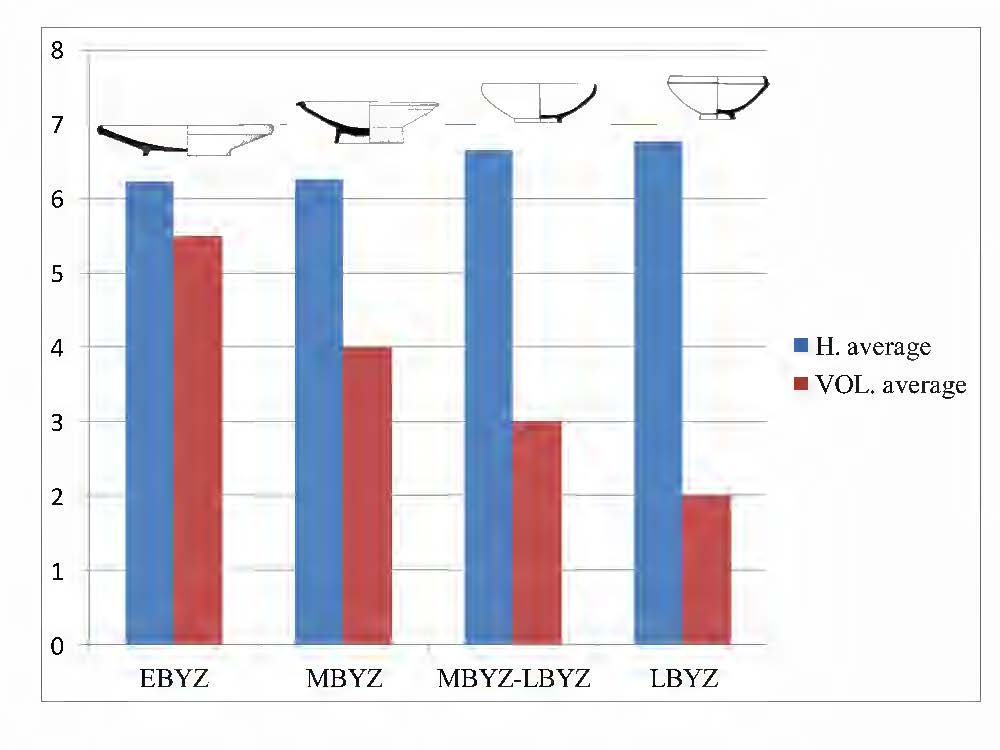

Apart from size, it is also worthwhile to measure the volume capacity of the Byzantine tableware. To do this, I have selected some pottery assemblages from the eastern Mediterranean, preferably from single datable closed deposits, ranging from Early Byzantine to Late Byzantine/Frankish times (ca. mid-seventh to fifteenth centuries). [48] When looking at the graph in Figure 11, it is clear that the height of the vessels goes up throughout the centuries, while the volume becomes less over time.

The same trend from Early Byzantine to Late Medieval times can be distinguished in excavated examples in combination with the iconography of that period. Measuring their diameter and height, the calculated volume of the Late Byzantine/Frankish vessels roughly ranges between 1.3 and 2.4 liters (Figure 10, lower register).

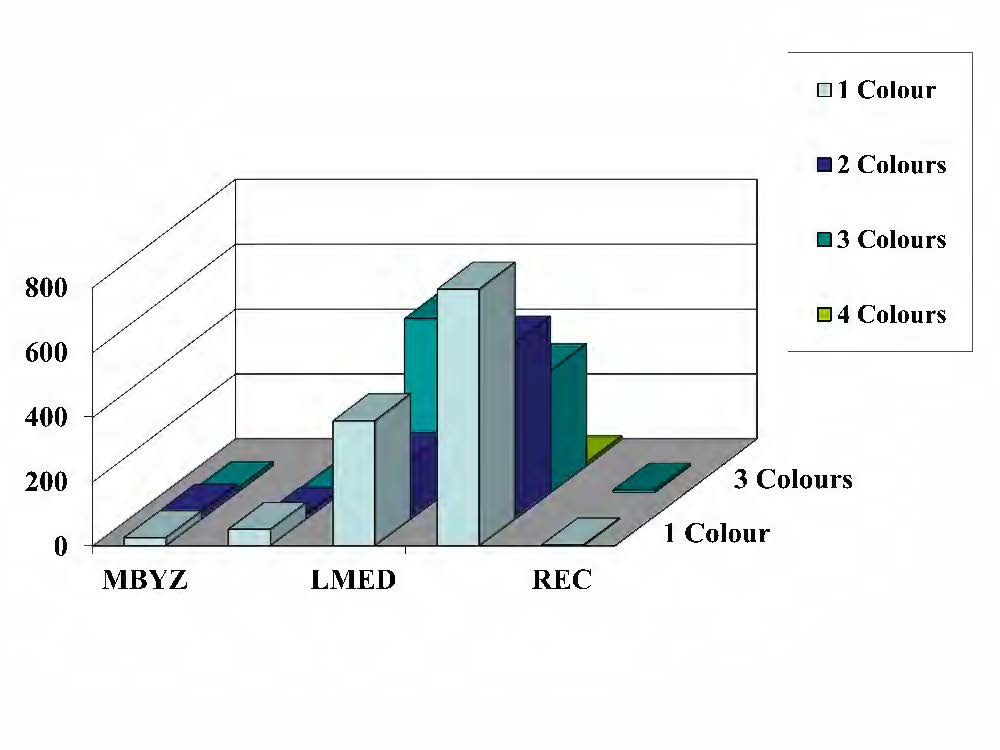

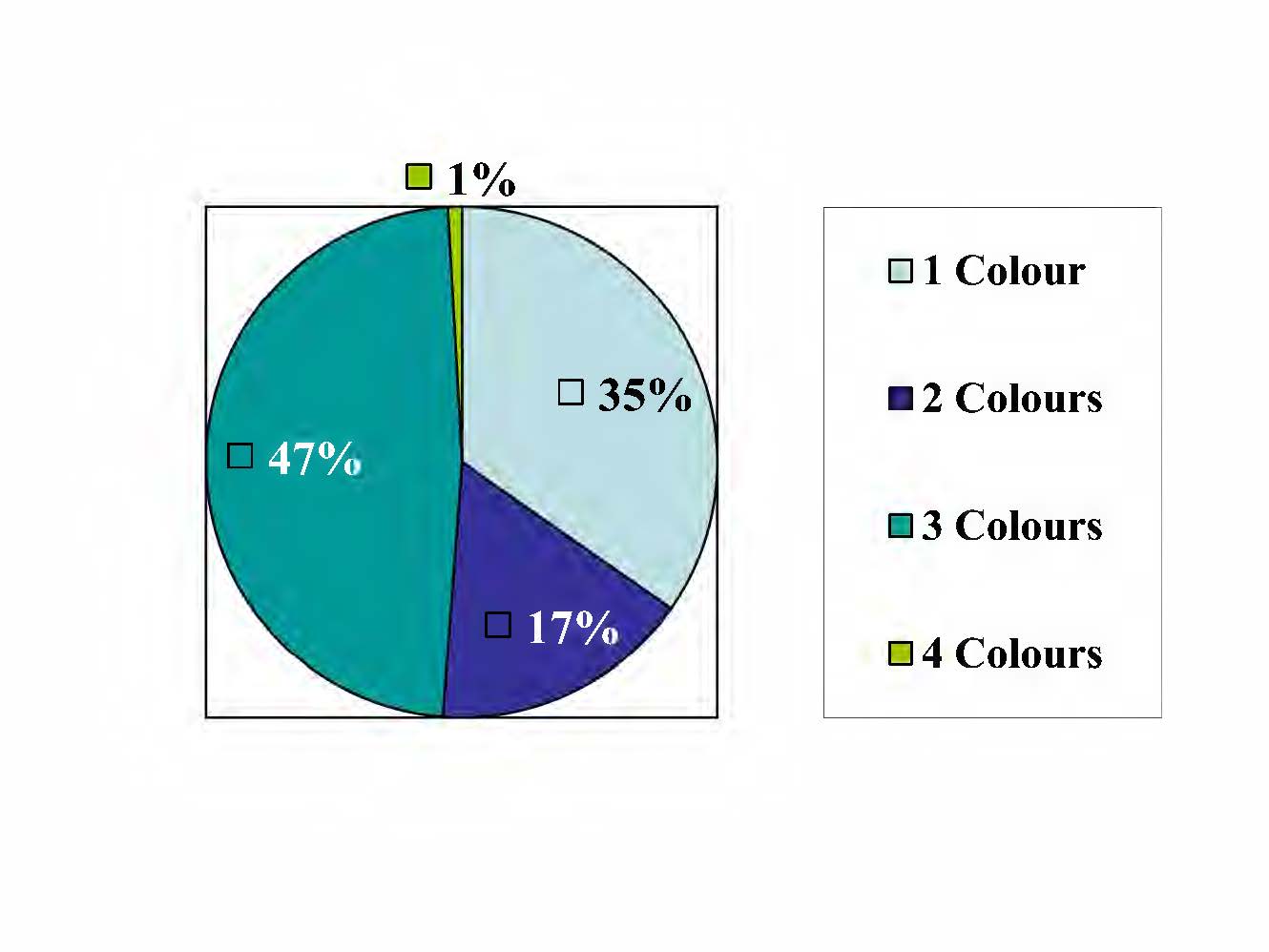

In addition, other trends in Late Medieval ceramics in the eastern Mediterranean shed light on new developments in dining practices. Of particular interest is, for instance, the use of different color percentages on pottery per period found at excavations in the so-called Triconch Palace at Butrint in southern Albania (see the graph in Figure 12). [49]

Although this is hardly explored territory, the presence or the absence of colored decoration on ceramics can contribute to the development of methodologies by which consumption patterns can be recognized in archaeological contexts. I have, therefore, divided the pottery assemblages from the Triconch Palace into decorated wares with one painted color, two painted colors, three painted colors, and, finally, four (or more) painted colors. After differentiating these four groups from Middle Byzantine to more recent times, it is obvious that the Late Byzantine/Frankish (here “LMED”) and Early Venetian periods (here “EVEN”) in Butrint produced by far the most colorful wares (Figure 13).

Smaller-scale dining and a new hierarchy of materials

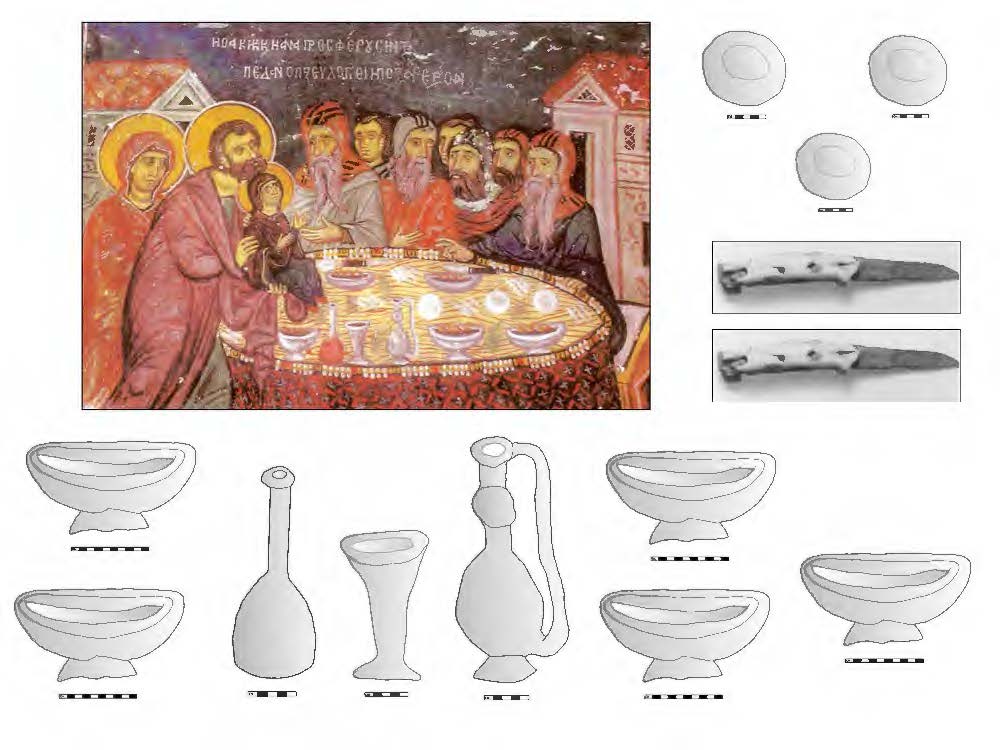

Many depictions of dining scenes of this later period show a quite sudden change towards a greater variety and a larger number of vessels, jugs, cutlery, and individual pieces of bread on the table. [56] The food is now divided into several smaller bowls, which were apparently shared by only three or four guests at the table. A fourteenth-century fresco from Cyprus for instance clearly shows this separation of food into various smaller bowls, as well as the individual use of jugs and even of glass beakers and glass wine jugs (Figure 15, upper left). [57]

Furthermore, the vessels with food and containers of wine or water on the fresco are not placed in a clear order on the table. The guests were expected to share the bowls and two knives between three or four men. Of particular interest is also that the wall painting shows simultaneously an oinochoe (a jug with a short neck and trefoil rim) and a potirion (a drinking cup) for the distribution and (individual or semi-individual) drinking on this table (Figure 15, lower register, center). [58]